By Ted Nordhaus and Alex Smith

In Part I of this series, we describe the conquest of the old materialist Left by the environmental movement in the post-war era. In Part II, we break down how the effort to transform Marx from modernization theorist to degrowther presaged broader center-left political debates about capitalism, biophysical limits to human aspirations, and the nature of social, political, and economic modernization. In Part III, we offer a very different reading of Marx. Were he alive today, he would almost certainly be an ecomodernist, not a degrowther, ecological economist, and perhaps not even a communist.

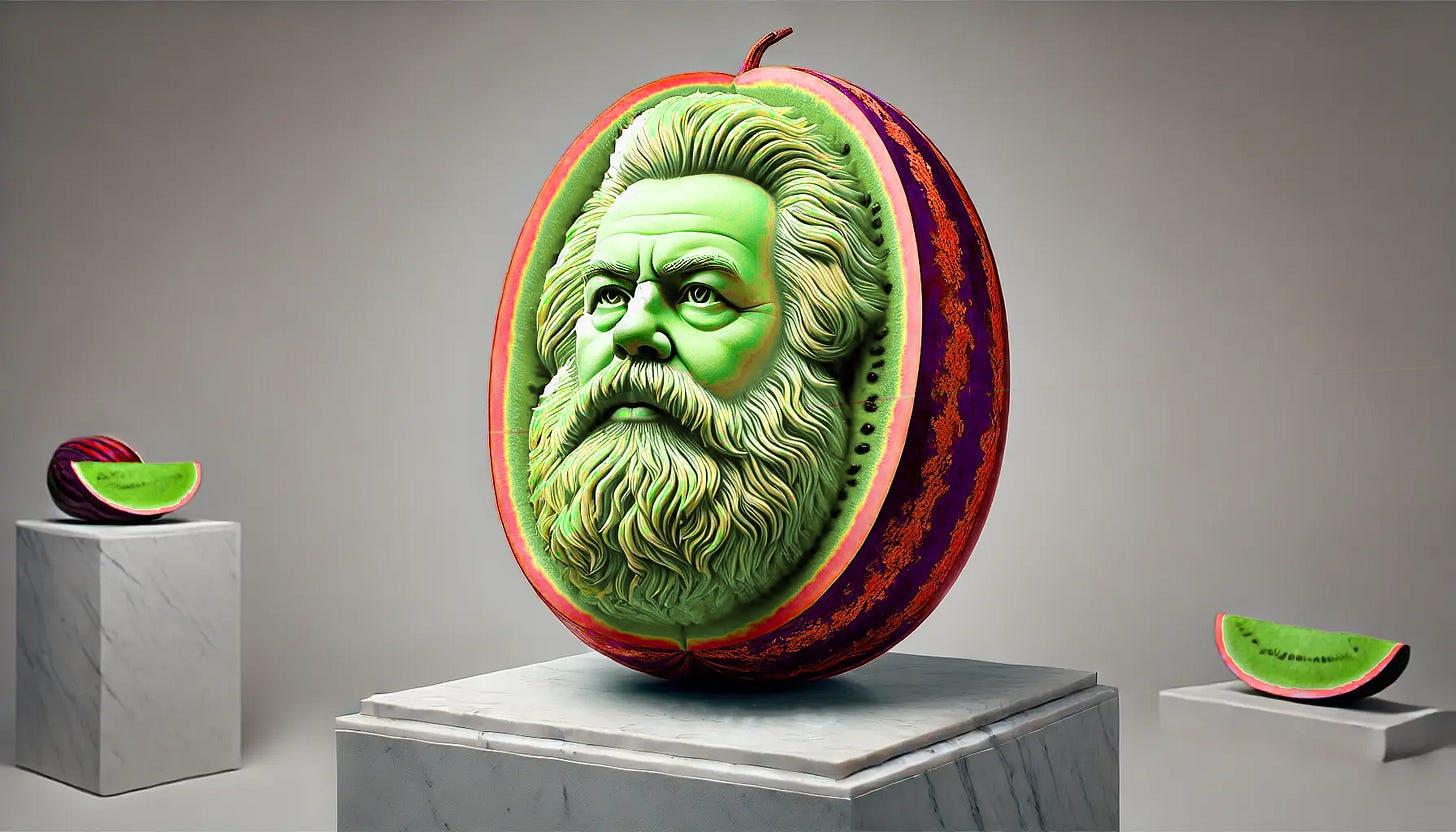

Part 1: Reverse Watermelon Politics

It doesn’t take much trolling around the internet to discover that Greta Thunberg is a Marxist. The climate skeptic website Climate Discussion Nexus has called her “Karl Marx in pigtails.” Thunberg, the Imaginative Conservative tells us, “is showing her true colors. And the color is red, not green.” The Spectator’s James Delingpole insists that Thunberg has “gone full Marxist.”

Thunberg is not the only prominent Marxist in our midst. Tucker Carlson, in recent years has compared the “church of environmentalism” to Marxism and described the Green New Deal as the “Great Green Leap Forward.” Indeed, the claim that environmentalists are really “watermelons,” green on the outside but red on the inside, is an evergreen cliché dating back decades.

Right wing critics of environmentalism, however, are not the only ones insisting that green is really red. Today, a very vocal cohort of left wing environmentalists deploy Marx under banners like degrowth and ecosocialism in the name of saving the planet.

But both the critics of watermelon politics and its proponents have the colors exactly backwards. The problem with the ecoleft today is not that they are hiding their communism behind a veneer of environmentalism, but rather that they are hiding their environmentalism behind a veneer of communism— they are red on the outside and green on the inside. This reverse watermelon politics reliably confuses capitalism with modernity, materialism with consumerism, and bohemianism with proletarianism.

The result is a class politics in which egalitarian elites, in the academy, NGOs, philanthropy, and the knowledge economy, wage economic war against the working classes. The new ecoleft revolutionary class demands regressive taxes, restrictions on consumption, and food, energy, and transportation policies that raise the cost of living for those least able to afford it—all justified by Malthusian claims that absent such measures, human societies will cross biophysical “metabolic” thresholds, resulting in apocalyptic consequences for humanity.

The core demands of the ecoleft are typically dressed up with a fig leaf of redistributionist socialism. The regressive nature of the new austerity will be leavened by redistribution, they insist, assuring that it is the rich, not the poor, who pay. But the tell that it is the “eco” and not the “socialism” that is in control here is that there is no clear theory as to how the post-capitalist ecoeconomy will produce economic surplus to distribute, or redistribute, fairly. It should not surprise that the most identifiably socialist features of the original Green New Deal—Medicare for All and a national jobs guarantee—were largely forgotten within months of Alexandra Ocasio Cortez’ election to Congress. By the time the Inflation Reduction Act passed years later, loudly trumpeted as a triumph of the activist Left, all that remained were green tax credits, with hardly a complaint from the erstwhile ecosocialists taking credit for its passage.

The old Marxist Left had a theory of the economy, how it produces surplus and value, and how both the quantity and quality of production changes as political economies evolve. The ecoleft has no such theory, insisting instead that less will be more and that new forms of connection, to each other and to nature, will make up for any material want. In place of a working theory of surplus value, the ecoleft offers little more than catastrophism and nostalgia for the feudal, pre-industrial past while proposing to impose ostensibly science-based ecological thresholds upon unwilling polities. Combining ivory tower nihilism with hostility towards the working class, reverse watermelon politics is both antithetical to anything that might be described as democratic socialism and disastrous for any prospect that the Left might succeed politically in the 21st century.

The Rise of the Ecoleft

Attempts to reconcile the historical materialism of the old Marxist Left with the ecological demands of post-war environmentalism date to the very earliest days of the New Left. As the baby boom generation, raised amidst post-war abundance, flooded into American universities, environmental concerns increasingly challenged materialist politics and liberatory demands based on race, gender, and sexuality complicated older, universalist notions of class solidarity and consciousness.

Meanwhile, America’s post-war working class had become arguably the richest in human history. What was good for General Motors did appear, to most, to be good for the country. America’s industrial proletariat was moving to the suburbs and buying tract homes with government-guaranteed mortgages—hardly the stuff of revolution.

And so the foundational texts of the New Left, like the Port Huron Statement and Herbert Marcuse’s seminal, One Dimensional Man, embraced a radical, if mostly underappreciated shift with profound implications for the modern Left. Because industrial abundance and welfare state beneficence had rendered the working classes unreliable allies in the anti-capitalist project, students, not the industrial proletariat, would constitute the revolutionary class in the advanced democracies of the West.

In that shift lay the seeds of two related political transformations. Liberal and left wing parties, despite continuing to fashion themselves as voices for poor and working people, largely became tribunes of the educated classes across the advanced developed economies of the West. This first transformation then enabled the second: the incorporation of environmentalism fully into the politics of the Left. Once the Left had divorced itself from actual proletarian constituencies, whose interests it purported to advocate but whose concerns it dismissed as “false needs,” the path had been cleared for environmentalism to capture the gentrified revolutionary classes of the post-war Left.

Through the 1970’s and 80’s, organized labor and environmentalists struggled for the soul of liberal and left wing politics across the developed world. But by the 1990s it was clear that ecology would trump labor ideologically and politically, a development that would herald the abandonment of the Left by working class constituencies. For a political faction whose increasingly elite composition belied its egalitarian values, this last development was problematic. But the response was not to refashion the Left to reflect the changing interests of the working classes in advanced developed economies but rather to refashion Marx and the history of the Left in the image of the new ecoleftists. Much of that work, initially, played out in obscure academic journals. And while “who cares,” is, at one level, a not unreasonable reaction, the intellectual gymnastic and talmudic debates involved in the effort to reconcile Marx and ecology that played out on the far left flank of center left politics also reflects a deeper conceptual rift that has challenged both liberalism and the leftist political project in the advanced, late-capitalist economies of the West.

In Part II of this series, we’ll break down the effort to transform Marx from modernization theorist to degrowther and how that effort touches broader center-left political debates about capitalism, biophysical limits to human aspirations, and the nature of social, political, and economic modernization.

Thanks for a thoughtful piece. One thought is that you see a split when the Marxists abandoned the working classes, essentially because they were more interested in leveraging the life and wealth that capitalism created than in destroying it. I would argue that that has been the case virtually everywhere since the socialist movement started in earnest in the 1840's. A good example is the Going To The People movement in 1870 in Russia. Students went to the people, but the peasants of the time laughed and rejected them and their ideas. So in Russia and other countries, Marxism became a belief system championed by students and the passionate few. This led to the emergence of Vanguardism, and the imposition of socialism by force for the good of the people.

I see a parallel in the environmental movement, especially with climate politics. While everyone will tell a pollster they care, their everyday actions do not reflect this..so the eco-passionate then seek to impose measures.

I am not saying this is right or wrong, and I certainly see a reaction now that is also imposing it's views from the top. Bith claim to speak for the bulk of Humanity and promise to avoid catastrophe. But they cannot get around the fact that most people will consistently choose to focus on their own lives and to make them as good as they believe they can, in both material and moral ways.