Why the Grid Is Lagging Behind Demand

A Short History of Grid Governance

By Deric Tilson

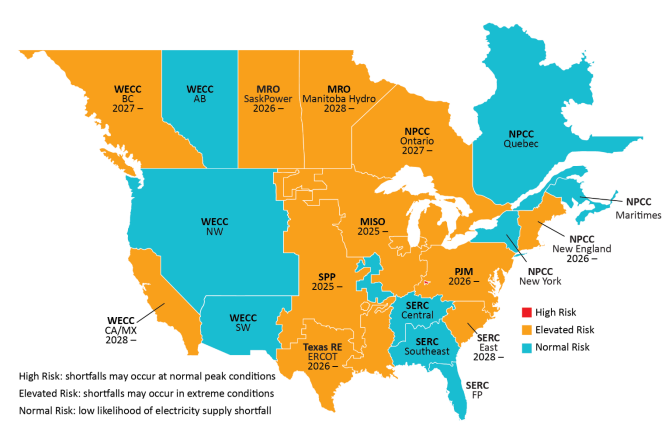

For the first time in almost 30 years, America’s demand for electricity is on the upswing—mostly due to datacenter growth and electrification. Yet, utilities and grid operators seem unable to meet this demand.

Sixty years ago, the grid was growing at a rapid pace, meeting the needs and wants of businesses and consumers across the nation; post-war expansion and economic growth were at their peak. During the 1960s, the total length of all high voltage transmission lines tripled to 60,000 miles, and electricity demand grew 8% annually. But in the decades since, America’s electricity system has stagnated, and the corporations and bureaucracies governing the grid have grown sclerotic. From 1970 to the 2010s, the growth of transmission infrastructure averaged 1.5% year over year, and electricity demand plateaued. Today, interconnection of new power plants takes six or more years, projects fail to get beyond the interconnection queue, and new transmission lines are not being built.

The failure of utilities, public utility commissions, states, and operators to respond to demand and build new generation and transmission is a direct outcome of how the grid came to be regulated and administered. The lack of interstate and interregional transmission being built has its roots in laws that were passed almost one hundred years ago that disincentivized any non-federal investment in interstate transmission. Understanding this history offers some possible directions on how to fix an electricity system that cannot make enough power or send it to the right places.

The Birth and Expansion of the Grid

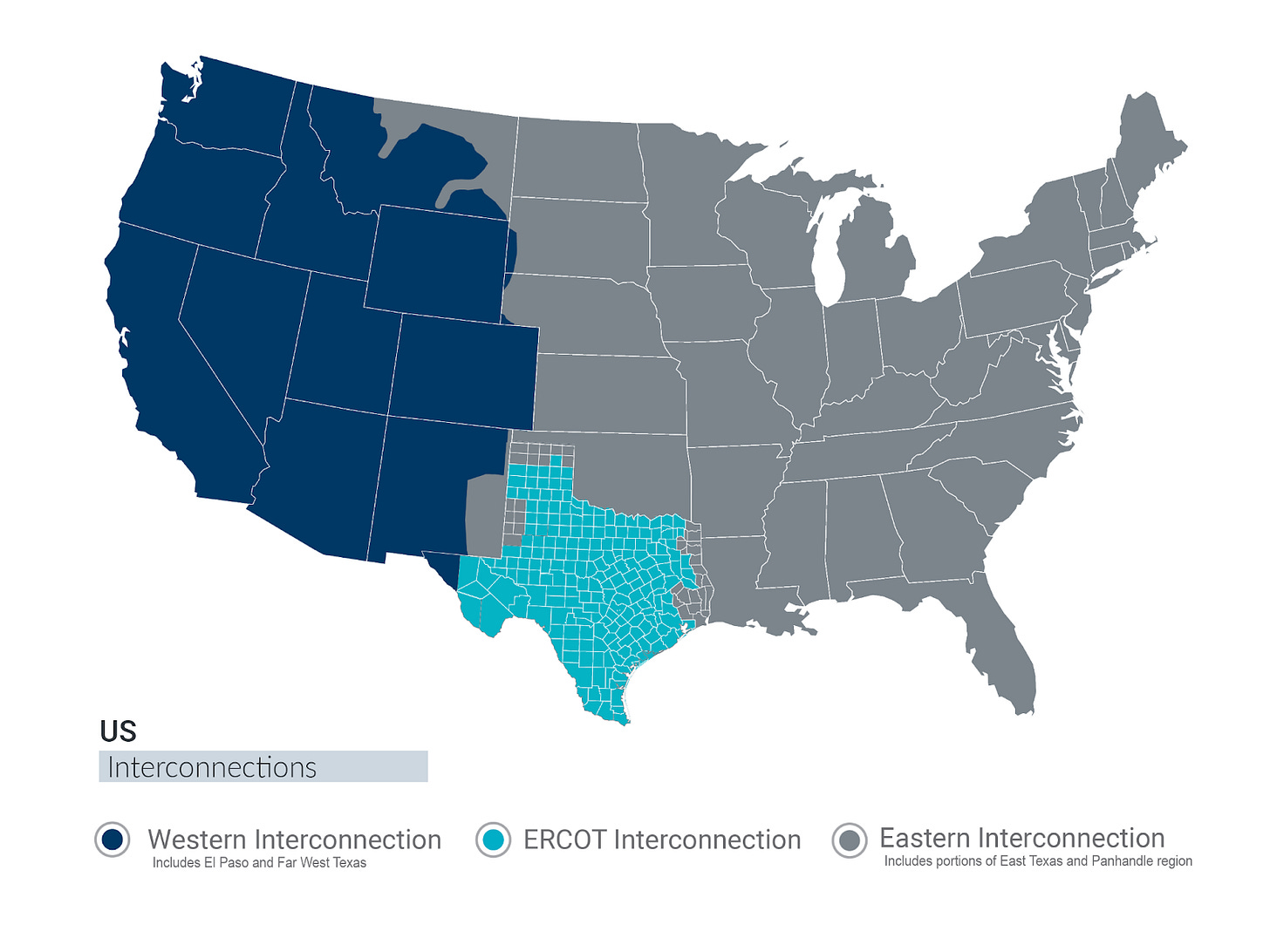

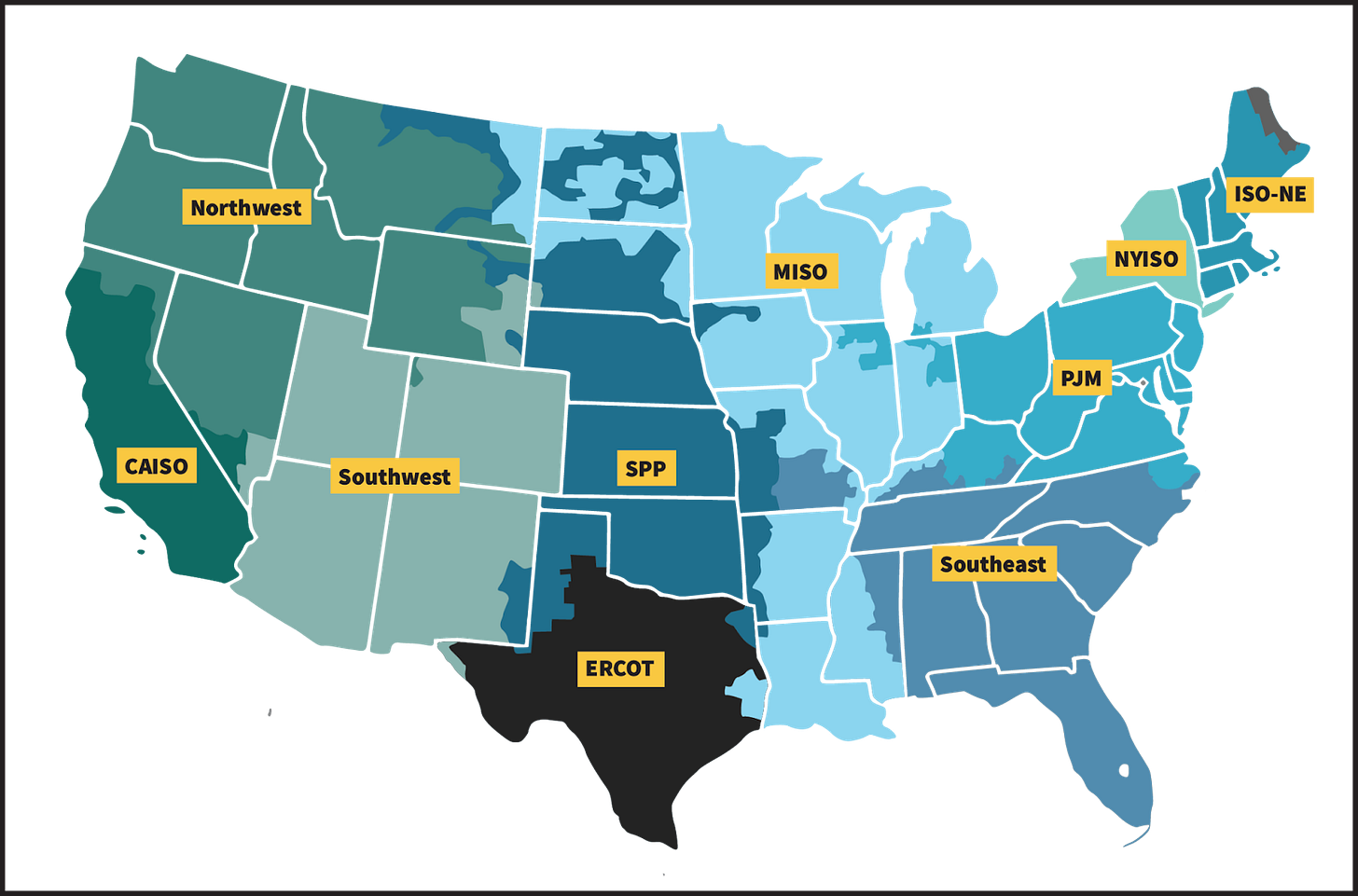

There are three electric grids, also called interconnections, in the United States: the Eastern grid, the Western grid, and the Texas grid. All three were started independently but have since grown to cover the United States.

The grids started in large cities and industrial centers. The Eastern Interconnection, a bit of a misnomer because the grid stretches from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains, started in New York and Chicago, where private electricity companies competed for customers and invested in growth.

In the West, the electrical grid grew outwards from hydroelectric dams. California saw the use of Pelton wheels to generate direct current (DC) power in 1887. In 1893, the Mill Creek No. 1 Hydroelectric Plant, in San Bernardino County, was the first commercial power plant in the United States using three-phase alternating current (AC). For the first time, power did not have to be consumed within a couple of kilometers from where it was generated. Two years later, the Folsom hydroelectric dam sent AC power over 21 miles to Sacramento, powering the capital building, lights, and streetcars. The electric grid continued to grow throughout the western states, and so did the utilities.

In the Texas Interconnection, electric power stations and distribution lines started in cities. Galveston had the first power plant in Texas in 1887. A hydroelectric dam was built in 1882 on the Colorado River, providing power to Austin. By 1912, transmission lines stretched from Waco to Fort Worth and then on towards Dallas. Companies began to agglomerate, but growth outward fell short when Congress passed the Federal Power Act of 1935 (FPA) and Texas utilities refused to interconnect with grids in other states with the intent to sidestep federal oversight. Texas’s grid remains unconnected from grids in other states.

Power pools, collections of interconnected utilities, began to form in the 1920s, with Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland (PJM) coming together as an early model in 1927 to build the Conowingo Dam and share its 200 MW of capacity. These power pools formed a kind of trade relationship; if a generator in Utility A experienced an outage, then one in Utility B could start up to make up the difference. The power pools increased the reliability of both utilities, and the reliability of these systems increased as more utilities joined.

Power pools grew during World War II as the demand for manufacturing and industry increased with the war effort. Some were centered around large aluminum smelters and other heavy industry that demanded tremendous amounts of power as they produced goods for the war. Even Texas formed a power pool during the war, known as the Texas Interconnected System, which later, after the inclusion of more utilities, became the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT). By 1964, there were over 200 power pools across the United States.

The reliability of electricity supply became a national issue following the first large-scale blackout on November 9, 1965. A single faulty relay in Ontario triggered a cascading failure across the northeastern US, southern Canada, and parts of the mid-Atlantic, leaving 30 million without power. Interconnections shared not only power but system failures as well.

As a result, the electric utility industry formed the National Electric Reliability Council (NERC) on June 1, 1968, to promote the reliability and adequacy of bulk power transmission. NERC’s mission was to “ensure the reliability of the North American bulk power system.” NERC, later renamed North American Electric Reliability Corporation without changing its acronym, maintains a watch over the reliability of the various electric interconnections in Canada, the US, and part of Mexico. It reports on the reliability of the interconnections and tracks data on the performance of transmission and generation. With NERC’s creation, reliability became a new goalpost in managing the grid. Potential generation projects must ensure their projects increase local system reliability; otherwise, the project owners may have to shell out additional funds to purchase and install network upgrades.

Agglomeration and Regulation

Grid regulation has evolved over the course of the last 140 years, but the initial conditions matter. Variations in policies formed a century ago, determining who gets paid, cost allocations, and contract details are still impacting market development and investment decisions being made today.

Regulation of electric utilities began in cities, many having multiple generation and distribution companies competing against one another. Chicago actively encouraged competition amongst its growing set of electric companies. Prices fell as a result. Over the years, electric companies began to merge and acquire one another until one firm controlled the local service area. Once this happened, in the absence of competition, electricity prices began to rise. Cities and municipalities were the first government entities to attempt to regulate the utilities and to keep the so-called monopoly power at bay; however, the utility service areas grew beyond the city’s jurisdiction. Across the country, utilities expanded their territories by buying up competitors and failing utilities. Holding companies provided a mechanism by which a small number of investors could obtain ownership of myriad power companies, many of them hundreds of miles away, without taking on a lot of direct risks. In some ways, transmission and distribution infrastructure leans towards monopolies; generation and transmission do experience economies of scale. Within the same technology category, larger power plants produce electricity more cheaply and efficiently than several smaller ones. Vertically integrated firms seemed especially conducive to the electricity supply chain, from generation to transmission to distribution. This tendency to go large and vertically integrate became a kind of technological determinism for the state regulation to come.

Massachusetts was the first state to create a commission to regulate public utilities in 1887. Twenty years later, Wisconsin Governor Robert La Follette Sr. created the first public service commission, vowing to keep monopolies in check. New York followed suit in the same year. The Public Service Commission of Wisconsin became a model for regulating utilities and provided a mechanism for setting the prices that utilities could charge consumers. In the thirteen years after the creation of the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin, more than thirty states created public utility commissions of their own. Many of them copied the legislation and rules of Wisconsin wholesale.

Once state-level regulation gained traction, the federal government stepped in with the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA) to help states maintain regulatory control. PUHCA, through what has come to be known as “The Death Clause,” ended the sprawling, decentralized nature of utilities and forced their operations into single, integrated systems. The utilities were constrained to one geographic area, many of them within a single state, and were prevented from engaging in transmission coordination across large areas. In return for these limitations, federal oversight, and the requirement to serve all customers at regulated rates, the utilities were given exclusive service territories and the right to earn a fair return on their investments. The utilities saw regulation as a way to protect their own interests. If a firm received monopoly status from the government, then the firm no longer had to be concerned with competition or the threat of new entrants. Furthermore, regulation guaranteed a return to investors and shareholders, something that would be threatened when competition lowered prices. Between 1935 and 1958, the number of holding companies fell from 216 to 18.

The FPA further constrained the activities of vertically integrated utilities, aiming to regulate the interstate flow of electricity, expanding the abilities of the Federal Power Commission (FPC). The FPA delineated regulatory authority: states could regulate generators, local distribution, and retail prices, but sales of wholesale generation and interstate transmission were under the jurisdiction of the federal government. The dual-jurisdiction model remains the primary framework for regulating the grid to this day, and is one of the primary barriers to building interregional transmission.

The Road to “Deregulation”

Large vertically integrated utilities regulated directly by the states were the norm across the United States until the 1970s. But the energy crisis changed the regulatory landscape. With the perceived corruption of utilities—research indicated states with public utility commissions were ineffective in lowering prices compared to non-regulated counterparts, and the regulated utilities continued to ask for ever higher rates—combined with the historically high energy prices of the 1970s, the federal government felt that states were too entrenched with incumbent utilities to handle the increasing prices. It was, after all, the state PUCs working with the utilities who had approved new large generators at the expense of the ratepayers. (At this time, states introduced an Office of Consumer Advocacy to vouch for the consumers against new infrastructure projects and increasing rates). To reduce prices, the utilities needed to be “deregulated.”

The so-called deregulation was a misnomer; the federal government sought to wrest control of electricity flows from the states and bring them under federal jurisdiction. Deregulation began with two pieces of legislation. First, the FPC was replaced by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in the 1977 Department of Energy Organization Act. With the restructuring of the Department of Energy and FERC’s placement as an independent agency, state energy policy and the actions of utilities were placed under the umbrella of federal energy policy. The most basic mandate of FERC is to “determine whether wholesale electricity prices were unjust and unreasonable and, if so, to regulate pricing and order refunds for overcharges to ratepayers.” Second, in 1978, Congress passed the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA), which mandated that utilities could not refuse to buy power from smaller generators and must allow that power to flow on their transmission lines without discrimination.

These two federal changes set the stage for the Energy Policy Act of 1992 (EPAct). EPAct mandated open access to transmission, which meant that a generator could sell its power across another utility’s transmission line. The transmission line’s owner earned a small fee, but it could not block a generator from having access to the line. EPAct allowed for the separation of generation and transmission, opening up competition for the first time since the 1900s, and enabled wholesale power markets to send power across utilities.

After EPAct, sixteen states deregulated their wholesale markets. The operators of these markets are called Independent System Operators (ISOs) or Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs), depending on the system. ISOs and RTOs are independent from the utilities, merchant operators, and transmission owners within their territory. The system operators use a “merit-based” trading system that matches energy demand to the lowest-cost electricity generator available, and then the next lowest-cost generator, and so on as demand waxes and wanes. Even with operators determining generation across multiple states, the policies of each state affect the investment in generation and transmission within its boundaries.

Problems Persist Despite Deregulation

With ISOs and RTOs, vertically integrated utilities and proactive transmission planning were both pushed out. Deregulation changed who paid for new transmission. Before, the utilities would assume the costs or share them with other utilities in the case of interregional transmission. With the disconnection of generation and transmission, the question of who bears the cost for transmission network upgrades, known as cost allocation, became a source of contention. In many of the deregulated markets, network upgrades are only considered when new generation is added. The new entrants complete an interconnection study with the system operator, deficiencies are noted, solutions are proposed, and the generator owner becomes responsible for those upgrades if they still want to pursue the project.

The transition to a deregulated market structure had plenty of growing pains. In the absence of strict regulator oversight, some companies like Enron took advantage of the loopholes and began manipulating the market. Enron would schedule transmission of energy across lines at certain times so it looked as if there was congestion. Enron would then get paid to relieve that congestion in the real-time market, even though it was taking no actual action. The company engaged in “ricochet,” a strategy in which it would export cheap Californian power to a subsidiary in another state and then have that power flow imported back into California at a higher price, avoiding the in-state generation price caps. Enron sold energy and ancillary services it did not actually have, and at other times submitted artificially inflated energy schedules, which caused confusion and chaos across the markets. The manipulations wreaked havoc on the California grid, causing multiple large blackouts. Market manipulations still occur today, but the operators employ market monitors who watch for and report suspicious behavior and wrongdoing to the grid operators and FERC.

Another complication is that deregulation does not mean that the market is not regulated. Take the Midcontinent Independent Service Operator (MISO), for example; it is a deregulated wholesale market, but the fifteen states that make up MISO each have a regulated retail market. This means that MISO determines the generation order using marginal pricing, but the rates paid by consumers are set by the individual states. It also means that the utilities get to maintain their government-granted monopoly status within their respective territories. Many of these states have what is called rate recovery; when utilities make upgrades to their generation fleet or transmission system, those costs can be recovered through higher rates paid by the customers. In MISO, the states kept the older regulatory structure while outsourcing the reliability component to a third party. At the utility and state levels, the incentives have not changed. This is why MISO has had a decline in the number of merchant generators over the past 15 years: they are being drummed out of the market by the regulated generators.

State-level policies and politics, from fads to longer-term thinking, affect the investments in the intrastate grid. The FPA removed any incentive and the legal ability for states to engage in interregional transmission planning. The states are permitted to site new transmission and approve new generation; however, with some exceptions detailed in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, states cannot be forced into approving and siting new transmission. When a new interstate transmission line is proposed, the line requires approval from the PUC of each state it passes through. States may block lines that they don’t perceive as benefiting their residents directly, even if they do in practice and are critical to the region as a whole. Generation, which can sometimes be substituted for transmission, is determined entirely at the state level without considering the needs of the broader region. States are often more focused on their own energy usage and needs than they are on the grid as a whole, even though a more robust and resilient grid would be beneficial to the individual states as well.

Much like states, utilities are incentivized against new interregional transmission lines and wholesale generation. A new transmission line may bring cheaper electricity to a utility’s service area. PURPA prevents the utility from refusing the cheaper power. In the intermediate run, fewer of the utility’s generating assets will be called upon, meaning lower revenues. Competition is antithetical to a utility’s interest and bottom line, whether the utility is in a regulated or deregulated market. Utilities push back in a number of ways, from lobbying the PUCs and state legislatures to filing regulations and rules related to their assets at FERC, a right granted to them in the FPA. Utilities have more say in designing grids and governance structures than is immediately apparent.

What Can We Do?

Even though the structures of utilities and markets have changed over time, regulatory decisions made over 90 years ago are still affecting the decisions made today. PUHCA constrained utilities to regional entities and enforced monopoly structures. FPA defined the jurisdictional authority between states and the federal government. These two laws removed the incentives and capability of any entity other than the federal government to engage in interstate transmission planning. States are enabled to be myopic in their energy planning and can block larger transmission projects that do not benefit their residents. Deregulation efforts in the late 20th century were not enough to spur growth in new infrastructure investments; many states maintain the right to choose which generation investments can be undertaken, or new investments may not make it past PUCs or consumer advocates, while in other regions, market entrants are on the hook for transmission upgrades that significantly increase the costs of projects. The governance of the grid has led to many veto points and frictions, even before a project reaches the permitting stage.

There is some hope; one path forward might be taking emergency measures. The backlog in the PJM interconnection queue has been so high that PJM requested fast-track interconnection for more than fifty projects through a new program called the Resource Reliability Initiative (RRI). This received major pushback from renewable developers and environmentalist groups, who saw the RRI as being prejudiced against wind and solar projects. However, the wait time for new infrastructure was heading towards a decade. Ten years is far too slow when reliability needs are manifesting in the present.

Texas stands apart from this issue in that it has allowed its electricity infrastructure to grow more rapidly than other system operators during the last several years. It uses an interconnection policy called “connect-and-manage” and uses price signals to determine transmission upgrades proactively. Despite being a red state, Texas has been able to add more renewables and transmission than any other state. Perhaps, ERCOT could be a model for regulatory reform and the buildout of energy infrastructure? The trade-off involved in switching to Texas’s approach is that Texas does not have a capacity market; the lack thereof led to $9,000 per MW pricing during Winter Storm Uri. A hybrid approach could be taken, combining connect-and-manage with capacity markets, but no one has made such a system.

One might ask, “Should the federal government take on a role in which it plans for transmission upgrades?” There is no incentive for any one utility or state to take this on. Reliability at the national scale is a public good. In ISO’s comprising many states, it is not easy to ensure reliability because of the variations in interests across the states. Centralized structures are not always the best for making decisions, but states are not self-interested enough in a market-oriented sense to ensure the robustness of the grid as a whole.

In the long run, the United States might just need a new regulatory regime. The one we have now was made when large fossil fuel and hydropower plants provided all of the electricity. New forms of energy generation have since been invented and are vying for space on the grid. Some proposals are looking for off-grid solutions. The needs of consumers and industry are growing and changing; the old system seems unable to keep up, especially as decentralized energy resources add layers of complexity to the grid. The old regulations may need to be done away with, and a new, more flexible system installed.

Nice summary of the history, but we need a solution. The attempts at introducing market incentives into the provision of electricity have proven to be a nightmare. I see three altenatives:

1) Return to the regulated monopoly, a system in which the more money the investor spends the more money he makes, and hope that the state regulators can control this perverse incentive. A good feature of this system is that the incentive to over-build usually leads to very reliable grids.

2) A single public monopoly which in the US I would institute on a state wide basis. At least then the least efficient monopolies will be exposed.

3) A hierarchy of coops. The coop approach handles the natural monopoly issue by making the shareholder the ratepayer. Such shareholders have no incentive to over-charge themselves. An outline of such a system is at

https://gordianknotbook.com/download/the-repower-plan/