Why Fusion Power Tomorrow Needs Industrial Capacity Today

The Plight of the Fusion-Industrial Tech Stack

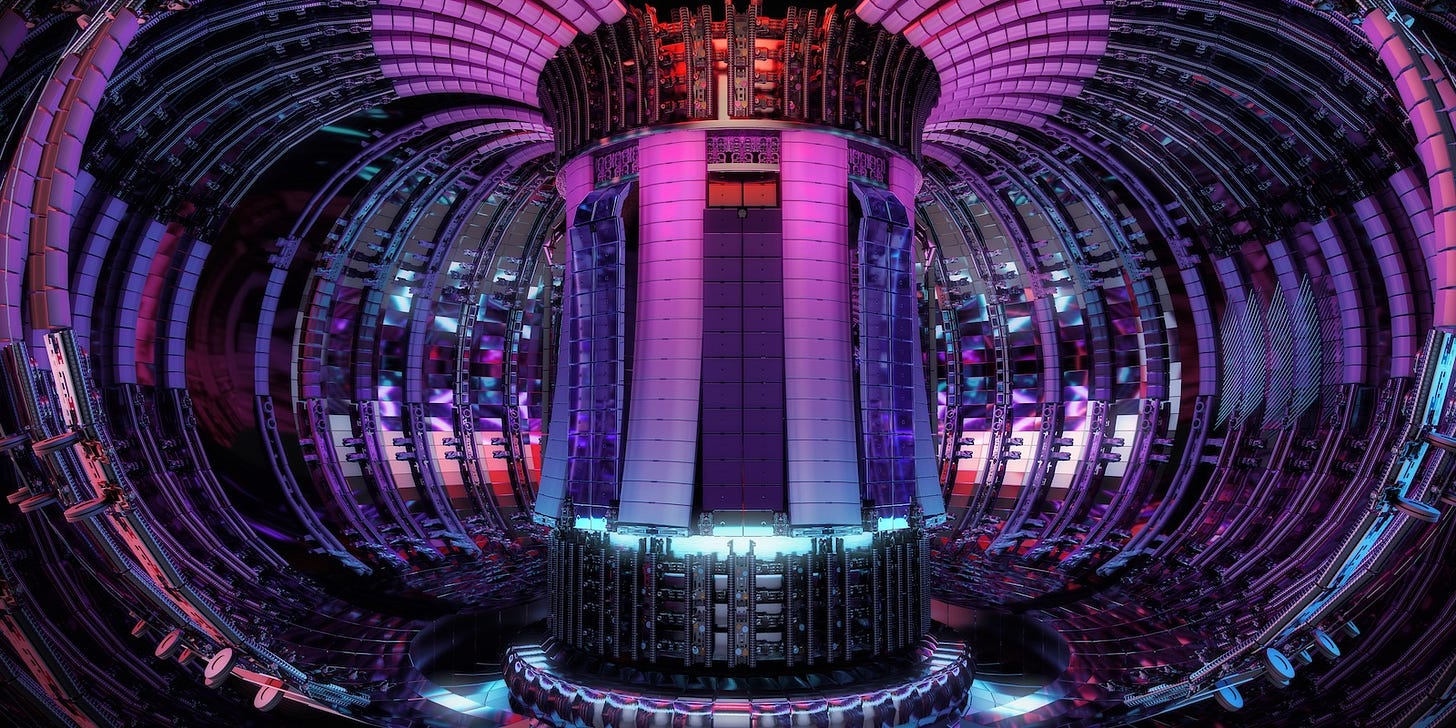

Nuclear fusion power aims to generate electricity by forcibly merging atomic nuclei, the same nuclear reaction that powers the stars. A perfect fusion power plant could theoretically generate zero-carbon electricity while producing a self-sustaining supply of fuel at the same time, leading some to dub fusion as the “holy grail” of “limitless” energy. These futuristic-seeming narratives—while laudably optimistic and admittedly very cool—do little to remind us that fusion is subject to the same economic and logistical forces as any other industrial project.

This bodes poorly for the prospects of fusion in the United States, a nation that misguidedly began to offshore industrial activity some 50 years ago and is now grappling with the consequences across the board.

These industrial woes are symptoms of what Harvard economists Gary Pisano and Willy Shih described in 2009 as the degradation of the “industrial commons,” in which decades of offshoring production sacrificed the shared process knowledge, skilled workforce, supplier networks, tools, and facilities foundational to making today’s technologies and to developing those of tomorrow. Noah Smith and Ryan McEntush have recently popularized a similar idea, the “Electro-Industrial Tech Stack,” detailing how electronics manufacturing is particularly cross-applicable: everything from laptops to smart refrigerators boils down to a collection of the same components—including batteries, computer chips, power electronics, and rare earth magnets—for which industrial capabilities can be transferred with relative ease.

America’s fusion industry is already demonstrating signs of struggling with the nation’s industrial atrophy. Helion Energy’s CEO describes procurement delays as the company’s single greatest risk, and Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) faced a lead time of more than three years for its tokamak—a donut-shaped fusion reactor—despite paying to ship the 50-ton vessel via airfreight across the Atlantic Ocean.

Building supply chains to serve fusion alone can’t be the answer. For America to lead in fusion and other breakthrough technologies, policymakers must internalize that the U.S. needs to rebuild its industrial commons. This requires proactive policymaking with an eye to the whole-of-economy benefits of “industrial tech stacks,” not simply targeting the minerals and manufacturing needs of a single industry or technology.

Building Innovation-Inducing Critical Mineral Supply Chains

Far-off visions of a world powered by limitless fusion energy first require building a massive number of fusion reactors. Today, this endeavor is less constrained by fuel access than critical minerals like yttrium and tungsten—both of which are in short supply in the United States, play crucial roles in fusion, and are financially bound to broad industrial activity.

Yttrium is a rare earth element that as many as half of fusion companies will use in rare earth barium copper oxide (REBCO)—a material that can carry electricity with 100% efficiency, that is, a superconductor. Superconducting magnets play a key role in magnetic-confinement fusion (MCF) machines by containing plasma while external devices heat it until atoms have enough energy to combine. Most companies pursuing MCF will use yttrium-based REBCO and are therefore tied to accessible and affordable yttrium to achieve commercial success.

The U.S. is 100 percent import dependent on yttrium, making procurement both onerous and, as of recently, prohibitively expensive. Between April and November of 2025, Chinese export restrictions pushed yttrium oxide prices up 4,400 percent, largely because 93 percent of American yttrium comes from China. While some hope that the federally-backed expansion of MP Materials’ Mountain Pass mine (the country’s only active rare earth mine) could become a future source for yttrium, a technical report reveals the company has no plans to specifically produce yttrium oxide, which makes up just 0.12 percent of the rare earth content in Mountain Pass bastnäsite ore.

Secure yttrium supply chains are needed to make domestic REBCO manufacturing economical—a crucial step towards creating a sustainable fusion industry in the U.S. A yttrium program, however, must focus on its uses outside of fusion: in LED and color displays, surgical and metal-cutting lasers, and the thermal barrier coatings that protect gas turbines, jet engines, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment from ultra-high temperatures.

Yttrium is also poised to catalyze innovations like quantum computing and hydrogen electrolysis. But, as with fusion, economy-wide supply chain pressures suppress the nation’s potential to seize leadership in these transformative technologies.

Tungsten is another crucial mineral for fusion with a constrained U.S. supply chain but significant potential to enable both economic and innovative activity. With a melting point over 3,400°C, the highest of all elements, tungsten boasts unique durability in extreme conditions. These properties make it essential in turbine blades, armor-piercing missiles, radiation shielding, and wear-resistant tools for oil & gas, mining, metalworking, and construction. For MCF, tungsten is a leading candidate for a reactor’s inner walls that face plasma hotter than the core of the Sun and continuous bombardment by high-energy neutrons. Fusion companies are exploring some alternatives to tungsten first wall materials, but mature industries have no commercial substitutes and therefore depend entirely on tungsten supply chains.

The U.S. has mined no tungsten since 2015 and imports nearly 70 percent of its tungsten, largely from Chinese-controlled supply chains. China, Russia, and North Korea control roughly 90 percent of global tungsten production, and Chinese export controls nearly doubled tungsten prices from $350/ton in April 2025 to $685/ton in October 2025.

While both yttrium and tungsten have military and defense applications—often the key criterion for a mineral to receive federal attention—the federal government has taken only meager action to develop new and lasting supply chains for either mineral. This is representative of a paradox for most rare earth elements and many critical minerals: their use in obscure settings masks their roles in powering modern technologies. For example, automakers wouldn’t have complied with the Clean Air Act’s ambitious NOX requirements had they not introduced cerium into catalytic converters in the late 1970s, and the network of submarine communications cables that carry over 99% of intercontinental data wouldn’t exist without erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs) made by Bell Labs in 1986.

Far from being an industrial policy, the Clean Air Act didn’t engender innovation by giving automakers specific tax credits to make catalytic converters. It succeeded because automakers in the 70s could rapidly access supply networks and manufacturing expertise for ceramics and glass and reorient them towards R&D and commercialization for a new product. In other words, they leaned on the nation’s industrial commons. In the same way, modern breakthroughs like fusion will rely on rebuilding an ecosystem of broad procurement and processing capabilities that, in turn, requires sustained investments across the entire U.S. economy.

Building Innovation On Legacy Semiconductors

Materials and manufacturing shortages, however, haven’t stopped the United States from cementing itself as a global leader in digital technologies. American companies continue to outpace competitors in computer chip design, and the U.S. is home to more data centers than the rest of the world combined. Innovation in AI models and high-end chip designs are amongst the highest priorities on the White House’s national security agenda.

But, legacy—not advanced chips—are likely to present the more acute bottleneck for America’s competitiveness in renewables, the automotive industry, 5G/6G internet, factory automation and robotics, military systems, and countless other hard tech sectors, including nuclear fusion.

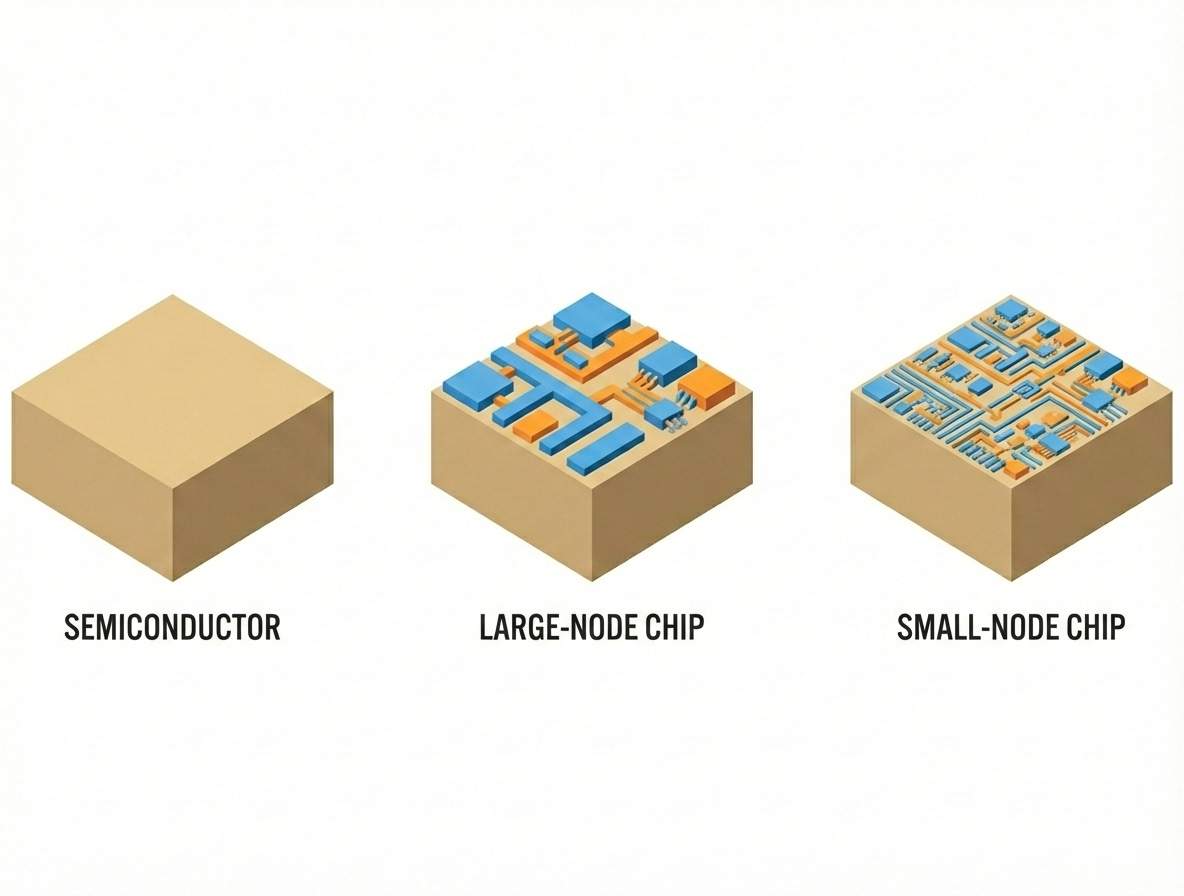

To understand why so-called “legacy” or “mature” chips are so important, we first need to clarify a few points about chip manufacturing and the role of chips in modern technologies. A chip is a functional product made by printing circuits onto a semiconductor material that has no logical capabilities of its own. Chips made with circuits, or “nodes,” larger than 28-nanometers (nm) are known as legacy or mature chips because etching bigger circuits onto a semiconductor uses older manufacturing technologies.

Small nodes pack more logic into a given area, making them well-suited for computer chips. But more computing power comes with a cost: small nodes are less stable, can only handle small quantities of electricity, and only work in a narrow range of environmental conditions. Not to mention that they’re more expensive.

Most electronics don’t need AI-capable logic and instead choose large nodes for their lower cost and better reliability. A chip used to lower a fighter jet’s landing gear doesn’t need the compute of a 3nm NVIDIA GPU but must withstand both 7Gs of G-force at 50,000 feet in the air over Alaska or baking amid 150°F heat in a desert hangar.

Similarly, monocrystalline silicon has exceptional properties for computer chips but is either too expensive or simply the wrong material for many other applications. For instance, most lasers that inject information into fiber optics run on indium phosphate, and RF devices from radars to garage door openers use gallium arsenide.

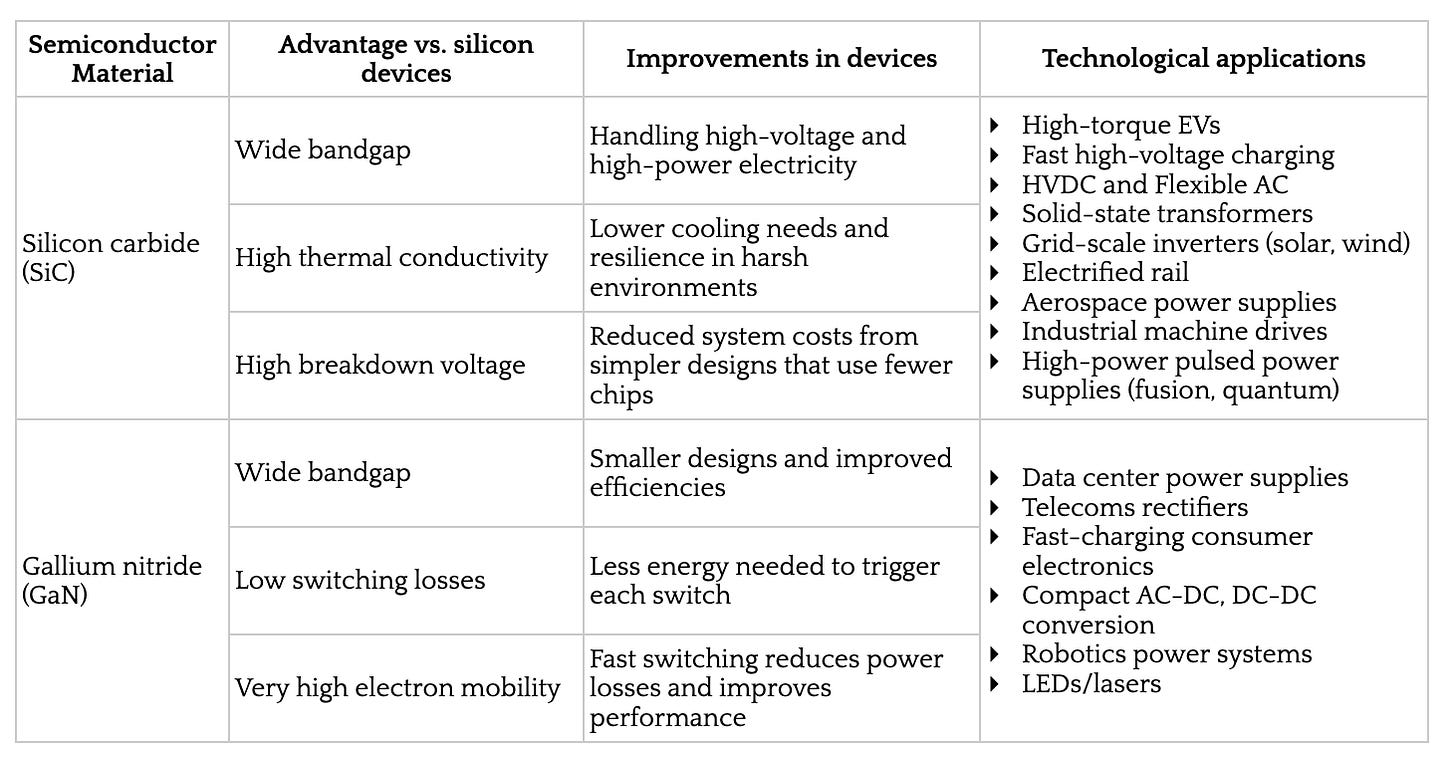

In fusion machines, mature chips built on next-generation semiconductors like silicon carbide and gallium nitride can increase performance while lowering costs. Silicon carbide (SiC) is ideal for high-temperature, high-power applications like delivering electricity to superconducting magnets, and the properties of gallium nitride (GaN) enable rapid switching speeds needed for plasma control systems to deal with process changes in real-time.

SiC and GaN have myriad uses in other transformative technologies from fusion. They will, in a sense, be the materials that underpin the “electro-industrial tech stack 2.0” as they become the gold standard in the next wave of electronics: self-driving cars, automated industrial facilities, 6G Internet, HVDC transmission lines, data center and EV power electronics. The list goes on and on, extending even to fusion.

But SiC and GaN are just semiconductor materials with no direct industrial utility. The companies and nations best positioned to capture the future of electronic technologies are those who control today’s manufacturing capacity for legacy chips and downstream products. We’re seeing the path-dependence of innovation play out in real time, and it perfectly exemplifies how the industrial commons acts as the foundation for technological progress.

Recent industrial policies in the U.S. weren’t designed to rebuild the industrial commons, a mindset reflected by the government’s receipts.

Of some $30 billion of finalized grants from the $39 billion made available in the CHIPS & Science Act, 85 percent funded projects to make advanced chips compared to just 13 percent for legacy chips and 2 percent for manufacturing equipment and chip-grade materials.

The above cost distribution further emphasizes how today’s industrial commons shapes the trajectory of innovation. America excels at making software and digital technologies and is pursuing massive data center buildout to support those industries. It’s only natural for government investment to skew in that direction.

But if the U.S. truly wants to innovate in hard-tech sectors whose supply chains it no longer participates in, industrial policies must concentrate on re-establishing an industrial commons capable of supporting innovation and directing investments according to the technical realities demanded by its stated ambitions.

The Tragedy of the Industrial Commons

Fusion has remarkably managed to avoid the many obstacles that routinely stall other advanced energy technologies, enjoying strong bipartisan support in both Congress and the White House, a navigable regulatory pathway, demonstrated backing from local communities, and deep ties to national labs and research universities. Having cut through the noise from these infamously nebulous hurdles, fusion offers an unambiguous look into how America’s anemic industrial commons is undermining the nation’s innovators.

Facilities around the world will certainly announce significant fusion milestones in the coming years that media outlets and social media influencers will use to evaluate who leads in the “race” for fusion energy. Such demonstrations will certainly constitute successes worthy of celebration, but the U.S. will only emerge victorious in such technological competitions by re-establishing a vibrant ecosystem of procurement and industrial capabilities—a multi-decadal decathlon that policymakers are oversimplifying to be a 400-meter sprint.

To harness fusion energy, meet new load growth, decarbonize the economy, or achieve any technological solution to a national goal, the United States needs to rebuild its industrial commons. To paraphrase Issac Newton: progress stands on the shoulders of giants.

Before assuming that fusion power will provide limitless energy at minimal cost, it might be well to remember wind and solar. Both were assumed to be much the same – limitless energy at zero cost – until bleak reality surfaced in all its impracticality. Similarly, EVs were assumed to be superior in all respects to conventional vehicles until their limitations became apparent. Has any serious effort been applied to what the limitations and drawbacks, if any, of fusion power might be?