What Climate Advocates Could Learn From US Soccer's Effort To Win the World Cup

Why Energy Policy Matters and Climate Targets Don’t

By Ted Nordhaus

In 1998, the US Soccer Federation announced a bold initiative to win the men’s World Cup by 2010. Comparing the effort to the Apollo moon landing, the federation launched Project 2010, a $50 million program to professionalize youth soccer development through a national residency academy along with other initiatives to identify world class talent and train it to compete at the highest level.

The idea was, to put it kindly, outlandish. The US had only recently returned to the World Cup, qualifying for the 1990 competition after a 40 year absence. The side had made a Cinderella run through the group stage and into the second round as the host nation in 1994. But in its other two appearances, in 1990 and 1998, it had lost all 6 of its games by a combined score of 13 - 3. Domestically, meanwhile, the nation’s only fully professional league, Major League Soccer, had launched just 2 years earlier and featured a handful of washed up international stars alongside a ragtag collection of former college and semi-pro players.

Needless to say, the US did not win the World Cup in 2010. It’s high water mark, in terms of World Cup performances, was an unexpected run to the quarterfinals in Japan and Korea at the 2002 World Cup with a team that featured two teenage products from the new residency academy, Landon Donovan and DeMarcus Beasley, alongside the same mix of former college and lower tier professional players that had been the staple of prior teams. In 2006, the team crashed out of the group stage, again failing to win a game. And in 2010 in South Africa, the team advanced from the group stage before bowing out to Ghana in the second round, for the first time with a roster composed entirely of seasoned professional players, a majority of whom played in Europe.

It’s not really clear whether anyone inside or outside of the US soccer establishment ever took the idea that the US might actually win the World Cup in 2010 very seriously. But my purpose here is not to interrogate the US soccer establishment but rather the climate policy establishment, which has serially embraced empty deadlines and temperature, emissions, and clean energy targets over the last three decades that have not proven to be much more credible than was Project 2010.

In this post, I’ll argue that energy policy matters but that climate targets do not. Long term public efforts to develop and commercialize lower carbon energy technology, initially to diversify national energy systems away from heavy dependence on oil and improve air quality and more recently to address climate change, have been hugely important. But while the diffusion of low carbon energy technology and diversification of the energy system away from oil and coal has required public action, it hasn’t happened in a fashion or on a timetable that anyone could have anticipated in advance. As a result, there is not much evidence that national, international, or corporate commitments to limit warming or to rapidly cut emissions and achieve net zero by particular future dates have had, or will have, much impact on the trajectory of future emissions, which are always already driven by a combination of macroeconomic forces and energy policies whose cumulative impact is impossible to predict in advance.

Missing the target

A moving goalpost of deadlines has been a chronic feature of both climate discourse and climate policy from virtually the beginning. From UN General Secretaries to US presidents, Al Gore to Greta Thunberg, policy-makers, celebrities, activists, and scientists have serially warned that the world had a short window to act to avert dangerous climate change. In 2006, Gore claimed that the world had a decade to take drastic action to avoid climate catastrophe. Over a decade later, the notion that the world had 12 years to avoid climate disaster became a rally cry among activists.

Pledges, targets and timetables for cutting emissions and deploying clean energy have been a reliable feature of climate policy as well. Shortly after taking office, the Biden Administration promised to cut US economy-wide emissions 50% by 2030, to achieve net zero emissions in the power-sector by 2035, and to decarbonize the entire economy by 2050. Not to be outdone, the European Union pledged to cut its emissions by 55% by 2030 and to achieve net zero in 2050.

The corporate world has followed suit. As of 2023, around 1000 publicly traded companies have made net zero commitments. These include companies with little obvious carbon emissions to reduce, such as the payment company Stripe, and those with very significant carbon footprints, such as United Airlines. Even oil and gas companies have gotten into the act, pledging at the COP28 conference in Dubai late last year to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, albeit only for those emissions involved in the production, refining, and distribution of oil and gas, not emissions that result from the combustion of their products after the point of sale.

Corporate climate pledges are mostly not worth the paper they are written on. Nor are grand pronouncements from politicians announcing targets decades hence, when they will have long since left office.

Arguably, government policies, such as the European Union’s climate law, or Great Britain’s 2006 Climate Change and Sustainable Energy Act, offer greater certainty that targets will be achieved. But one need only consider the head-spinning US policy shifts over the last two decades, as the Bush Administration pulled out of the Kyoto Accord, the Obama Administration then negotiated the Paris Agreement in its place, the Trump Administration withdrew from Paris, and the Biden Administration rejoined it, to see that long term climate and clean energy commitments are only really good until the next election.

America’s polarized political environment may be extreme. But similar dynamics have long been evident elsewhere as well. The fact that the Kyoto Accord was negotiated on home soil didn’t stop Japan from walking back its commitment to reduce emissions during the agreement's second compliance period, after it shuttered its nuclear reactors in the aftermath of the Fukushima accident. Canada, around the same time, withdrew from the Accord to avoid paying $14 billion in penalties for non-compliance with its Kyoto commitments. Germany and a number of other EU members were on track to substantially overshoot their 2020 climate targets until the collapse of emissions during the first year of the Covid pandemic intervened. And it is not hard to imagine the EU abandoning its current climate law should right wing nationalists sweep into power across the continent later this year, as many observers fear.

Insofar as nations have met emissions commitments, it has been macroeconomic misfortune, not climate policy, that gets most of the credit. The EU pushed hard in the run up to the Kyoto Accord to peg emission reductions to a 1990 baseline, which allowed Europe to benefit from the collapse of Eastern Bloc economies after the breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The sustained recession after the global financial crisis kept emissions depressed in many developed economies that had made Kyoto commitments in the final years of the first Kyoto compliance period. And, as noted above, the social and economic catastrophe that was the Covid pandemic conveniently coincided with the final year of the second Kyoto compliance period, to which many national emissions policies were still tied even though Kyoto had been superseded by the Paris Agreement.

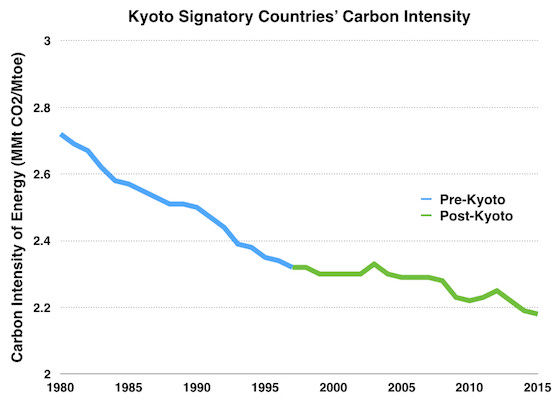

Indeed, it is hard to identify any direct or obvious effect of climate or energy policies tied to these sorts of targets once one controls for relatively short term macroeconomic swings that heavily influence emissions from year to year and even decade to decade. As Jessica Lovering and I demonstrated in 2016, there is little evidence that the carbon intensity of global or national energy systems fell faster after global agreements like the Kyoto Accord or policies to ostensibly cap and draw down emissions such as the European Emissions Trading Scheme or California’s cap and trade program.

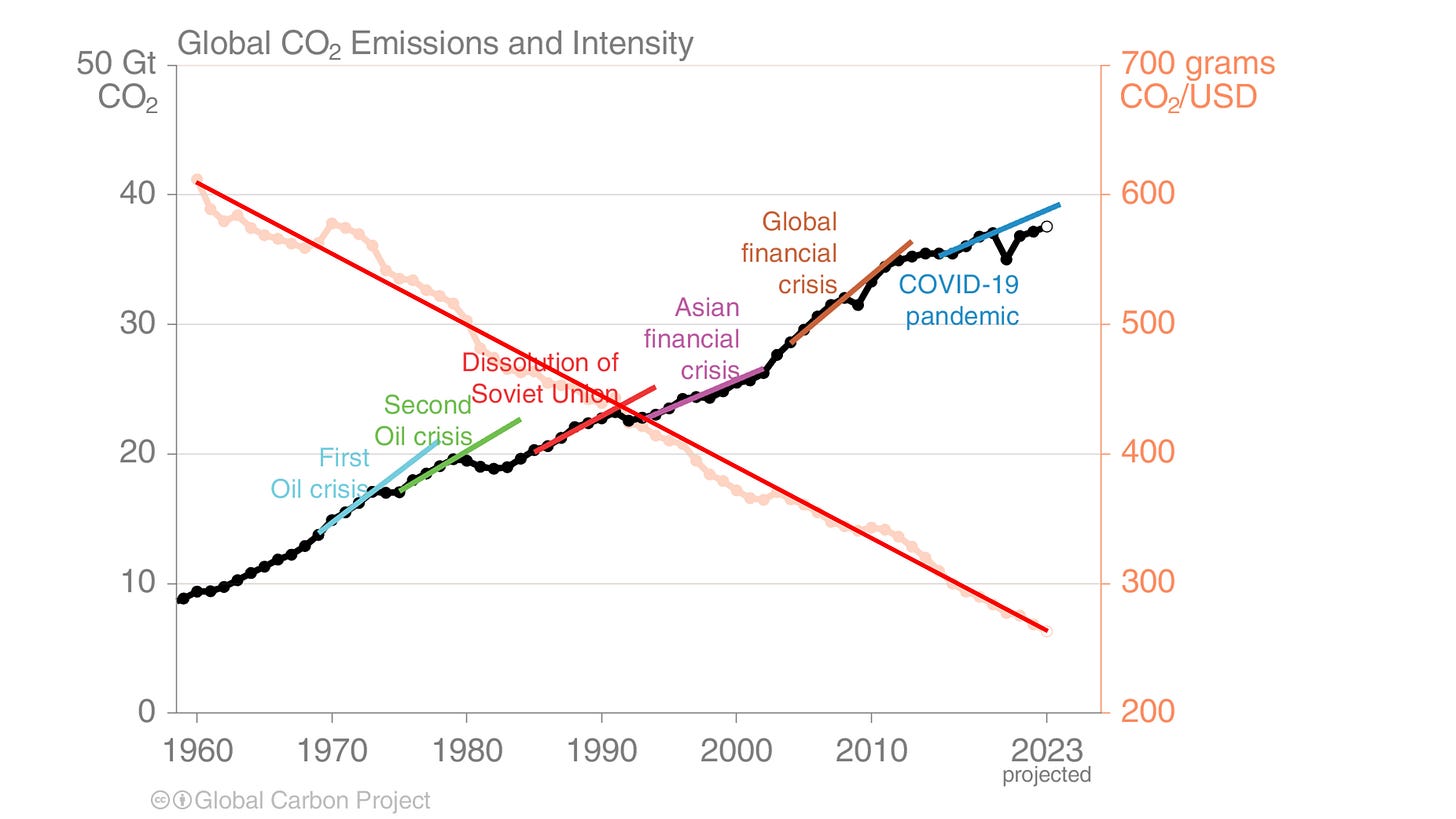

More recent analysis by Roger Pielke Jr shows that there has been no change to the trajectory of the carbon intensity of the global economy going much further back, to the oil crises of the 1970s and perhaps before.

Policy matters, targets don’t

The best case for setting ambitious targets is that doing so mobilizes policy and resources even if we don’t hit our mark. But the fact that so many targets at the international, national, and sub-national levels have come and gone over the last three decades without any discernible change in the long term rate of decarbonization suggests that either this sort of goal setting is ineffectual or that long term decarbonization is actually a product of these efforts, the latter case implying that without all the target setting, decarbonization would have proceeded slower and emissions would have risen faster than they actually have. But the fact that the advent of effective decarbonization policies began several decades before anyone started making these sorts of promises about climate change or clean energy suggests that the targets and goal setting that have characterized so much climate policy-making and discourse have been at best unnecessary and at worst a distraction.

And yet, while the long term and linear trajectory of decarbonization undermines the case for climate and clean energy targets, it also suggests a really important role for energy policy. If there has been an inflection point in the trajectory of the modern global energy economy, it is not 1992, when the nations of the world first convened to discuss what to do about climate change but rather 1973, the year of the Arab oil embargo.

The series of energy price shocks in the decade that followed resulted in a dramatic shift in government efforts to diversify energy supplies and reduce the energy intensity of national economies. And while it is difficult to quantify the exact magnitude of the shift because the new era marked not only a massive step up in policy efforts to shape the energy economy but also the beginning of most official energy statistics keeping, it is clear that global primary energy production has diversified significantly away from oil and coal since then.

In 1973, oil and coal, the most carbon intensive sources of energy, accounted for 70% of global primary energy. Today, oil and coal account for around 58% of global primary energy even as global primary energy consumption has more than doubled. Natural gas, which emits about half as much carbon dioxide as oil or coal, took up some of that share. The rest was made up by low carbon energy produced with nuclear, hydro, wind, and solar.

So one view of the historic rate of global decarbonization, going back to the early 1970s, is that it was always already a product, at least in part, of public policy. Nations, and most especially developed economies, made prodigious efforts -- via publicly-funded research and development programs, state-led deployment of new technologies such as nuclear energy, demonstration projects and subsidies to commercialize renewable energy and unconventional oil and gas production, and energy efficiency standards and regulations — to reduce their vulnerability to energy price shocks and dependence upon a single commodity - oil - that was both in short supply and controlled by states that were, if not always hostile, not always reliable either.

This would suggest that it has taken significant policy effort just to establish and maintain the global and national decarbonization trends that we have seen since the early 1970s and will likely take significant further effort to sustain it into the future. Those past efforts didn’t always succeed. For every shale gas revolution, there was an oil shale or synfuels fiasco, for every solar photovoltaic success, a concentrated solar failure. And they didn’t happen everywhere at the same time. Early US efforts to commercialize wind and solar spilled over to programs in Scandinavia, Germany, and southern Europe, which in turn provided both the technology and market for China’s massive efforts to turn itself into a clean energy manufacturing colossus.

Decarbonization, in this way, is an emergent feature of global modernization, occurring at a somewhat predictable rate, at least over the long term, but not on anyone’s timetable or, mostly, according to anyone’s plan. In a few places, brute force state-led policy drove rapid decarbonization. France, bereft of any significant fossil energy reserves, centrally planned a nuclear buildout that deeply decarbonized its electrical grid in about a decade. But even France, which made substantial effort to “electrify everything” long before it became a talking point for climate advocates, hasn’t made similar progress outside of the power sector.

That is arguably the best case. In a lot of other cases, important progress in decarbonization came in unexpected ways. Nobody paid much heed to shale gas until it was already transforming global energy markets and accounting for the lion’s share of US decarbonization over the last 15 years. Many people, including me, didn’t foresee the rapid reduction in solar and wind costs that followed China’s massive commitment to scale up manufacturing in the years after the global financial crisis. By the same token, many renewable energy advocates who saw in that development proof that endlessly cheap and abundant wind and solar could meet the world’s energy needs if the world simply decided to scale it up, failed to anticipate the problem of value deflation as a combination of cheap manufacturing and continuing deployment subsidies pushed increasingly high penetrations of variable renewable energy into electricity grids.

The paradox here is that a lot that has driven decarbonization over many decades was both connected in some way to public efforts to develop and deploy technology and impossible to predict. For this reason, climate and energy policy both matter a lot and won’t get us to any particular destination with any certainty or precision. Like it or not, there simply isn’t a knob in the White House or anywhere else marked climate or energy that anyone has any idea how to turn with any confidence, much less precision.

The case for humility (and against technocratic hubris)

The conceit that we know how to deeply decarbonize the global economy and can do so on a timetable has consequences that are not always obvious. Continually setting and missing targets breeds cynicism among both those making commitments and those for whom they are intended. Technocratic confidence in the capacity to select the pathways, technologies, and timetables for decarbonization often overestimates the readiness of current technology, under emphasizes the limitations, and imposes substantial costs upon those least able to afford or manage them. Ten point plans and energy system models are frictionless and perfectly optimized. The real world is a kludge of tradeoffs, inefficiencies, perverse incentives, and irrationalities.

That is not an argument against climate or energy policy. Sustaining current rates of global decarbonization probably depends upon it. But it is an argument for humility. We simply don’t know what will work and what won’t. Insofar as we can figure out how to bend the historic decarbonization trajectory a bit faster toward net zero we should by all means do so. But it is worth remembering that the climate, against the constant incantations of the climate movement, does not have a deadline. There is no biophysical evidence, or even theory, suggesting that catastrophe lies beyond 1.5 or 2 degrees of warming.

The good news is that if we can simply sustain the post-1970 rate of global decarbonization, the world will hit net-zero emissions around 2080. That won’t be fast enough to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees. But it would probably keep us somewhere in the neighborhood of 2 degrees.

Would I bet on that? No. Decarbonization will likely get harder as we try to squeeze the last emissions out of difficult to decarbonize sectors. But one thing I’m pretty sure of is that technological change, ever unpredictable and uncertain, not bold pronouncements or policies reverse engineered to achieve arbitrary climate targets, will determine where we end up and when we get there.

At 58 years old, I doubt I’ll live to see either a US men’s team win the World Cup or net zero emissions globally. But it’s also worth remembering that any landscape is difficult, often impossible, to fully see while one is smack in the middle of it. What can seem a hopeless and frustrating situation in one moment in time can quickly turn promising, and vice versa.

To wit, 20 years after US Soccer unveiled its grand plan to win the World Cup in 2010, the men’s team hit its nadir in the modern era, failing to qualify for the 2018 World Cup by losing to a far less talented Trinidad and Tobago team on the last day of qualifying. And then, over the next several years, a new generation of young Americans started turning up in top sides all over Europe. This season, Americans assisted on more goals in the top 5 European leagues than any non-European nation other than Brazil and Argentina.

What turned the tide was not the audacious goal to win the World Cup in 12 years but the slow maturation of the game in the United States. A single national residency academy was, at best, a stop gap measure. Today, MLS features 29 teams, all with development academies that identify and develop youth talent in a professional environment. They compete for talent not only with each other but academies established by European sides like FC Barcelona and a range of other independent development academies. As a result, there are exponentially more young American players being trained in professional environments from a much younger age.

The US is still a long shot to win a World Cup when it again hosts the competition in two years time. But the team it will put on the field will not look anything like the team it fielded in 1994. That progress should remind us that there is a fine line between ambition on the one hand and hubris and delusion on the other. The best defense against the latter is to focus a lot more on the direction of travel and a lot less on the destination. When the sun sets on the most recent round of global climate target setting, as seems likely over the next few years, we’ll be well served to keep that in mind.