Understanding the NRC Independence Debate

The NRC Has Never Been a Wholly Independent Agency, But That’s Not Necessarily a Problem

By Adam Stein

In a February executive order, the Trump administration asserted that “so-called ‘independent regulatory agencies,’” exercise too much executive power without accountability to the President. According to the EO, these agencies, including the Nuclear Regulatory Committee (NRC), Federal Communications Commission, and the Environmental Protection Agency, among many others, would have to submit all regulatory decisions to the White House prior to their finalization.

A set of nuclear-related executive orders issued in May included one ordering the reform of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The order sent ripples through Washington that are still being felt, including amongst the nuclear advocacy community that has been working, for years, to reform the NRC and modernize nuclear regulations to enable growth for the industry. What the order means for the NRC, its independence from political offices, and for progress in the fight for regulatory modernization is still up in the air.

In June, the White House abruptly dismissed Commissioner Christopher Hanson, a Democratic appointee whose term ran through 2029. The dismissal was followed by a controversial statement attributed to the DOGE lead at the NRC that he expected the agency to “rubberstamp” reactor designs already approved by the Department of Energy. Members of Congress and former NRC Commissioners and staff reacted to the statement, warning that it risks politicizing safety oversight.

Together, these developments have sparked a renewed national debate over the independence of the NRC and what it means for a technically-oriented mission-driven regulator whose credibility underpins public trust and international confidence in nuclear power.

However, most partisans in this debate don’t understand the nature of the NRC’s independence, or its statutory history.

It is true that the NRC must remain a regulator that has the authority and capacity to take necessary actions to achieve its statutory mandate, and is independent of, and not influenced by, the nuclear industry. But, when it comes to the NRC’s independence from other parts of the federal government—a factor in the NRC’s capacity to fulfill its statutory obligation—the reality is more complex. In short, the NRC has never been fully independent from other parts of government; instead, it is built on layers of independence and oversight.

The Independence Needed to Fulfill Statutory Objectives

The Atomic Energy Act of 1954 (AEA) established the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to have authority over atomic material and technologies, including energy, industrial, and medical uses, and for research and development. A Commission structure was used to ensure a range of input from members with technical expertise could make judgements on licensing decisions and be independent of industry influence.

The Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 (ERA) abolished the AEC and established the five-member Nuclear Regulatory Commission to take over licensing and regulatory authority from the AEC. The NRC was created to “promote well-balanced and closely supervised regulation of the burgeoning nuclear power industry” separate from the development and promotion activities of the newly created Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA). The final version of the ERA calls the NRC an “independent regulatory commission” and the ERDA an “independent executive agency.” The ERDA was later rolled into the Department of Energy.

Congress, through the AEA, gives authority to the Commission to set policy and regulations directly. Specifically, the Commission has authority to determine what requirements it deems are appropriate and necessary to obtain an operating license, and to take actions to achieve its statutory mandate. Critically, only the Commissioners can issue reactor licenses, not the NRC staff, nor the President, or any other political or bureaucratic leader. And, if a reactor meets the stated requirements, the Commission does not have the authority to withhold a license.

The mission of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission is to provide adequate protection for the health and safety of the public, common defense and security, and protect the environment, while maximizing the contribution of nuclear technology to the general welfare. This provides the policy priorities for the NRC; it must always enable nuclear technologies, while also requiring the rigor and protections necessary.

In the case brief for Siegel v. Atomic Energy Commission (1968), Judge Carl McGowan of the U.S. Court of Appeals identified the commission’s independence as key to the NRC’s success, writing that Congress enacted “a regulatory scheme which is virtually unique in the degree to which broad responsibility is reposed in the administering agency, free of close prescription in its charter as to how it shall proceed in achieving the statutory objectives.”

That level of independence is very important to avoid incentives or pressures to approve a technology or application that does not meet the mission of the agency. Those incentives could exist in a case where there was pressure to complete a project, but safety evaluations either were not completed or determined that the project should not be completed. That is the independence that is critical to maintain to avoid outside parties—whether a presidential administration, industry groups, or congressional offices—from undercutting the work of the NRC to benefit society and enable nuclear technology.

But the NRC Has Never Been Completely Independent

Presidential administrations and Congress have always had political influence over the Commission. Because commissioners are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has never been fully independent from politics. Congress understood this when the Commission was originally created and required that no more than three commissioners could be from any one political party, in order to “maintain political balance” while also setting staggered five-year terms to create regulatory stability.

Appointments have been used to implement higher-level political goals in the past. Commissioners have been appointed with the intent to make regulations stricter, scale them back, provide balance, stop progress on spent fuel storage at Yucca Mountain, or expand regulations in response to the incident at Fukushima Daiichi. While serving their term, some commissioners stay at arms-length from elected officials, others stay very engaged with Congress and the Administration.

The Commission also needs to have budgets approved by the President through the Office of Management and Budget and, more recently, rules approved by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. The President also has the authority in the AEA to remove Commissioners for cause, defined as inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance. This is an oversight backstop to prevent Commissioners who are not doing their job from staying in that role. But, the backstop has been rarely used, even when the Commission has not been efficient in fulfilling its duties.

Since Congress passed the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act in 2019, mandating regulatory reform, the Commission has taken an average of 270 days to vote on policies and rulemakings submitted by staff, despite internal procedures that set the standard of completing votes in 18-60 days. In that span, only 20% of votes were completed on time. Despite this, no Administration sought to remove Commissioners that were neglecting their duties.

Separately, in 2011 four Commissioners sent an unprecedented letter to President Obama’s Chief of Staff, raising significant concerns about former Chairman Jaczko’s abuse and intimidation of NRC staff and the ACRS into following orders. Congressional Democrats maintained support for him, complimenting him as “the best chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in its history,” Congressional Republicans issued a report that suggested Jaczko withheld information from other Commissioners and suggested that votes could be seen as a lack of support for the Obama administration—a parallel to current concerns. Instead of removing him as the Chair or unseating him as a Commissioner, President Obama’s Chief of Staff directed the Commission to seek third-party help, and quietly pressured Jaczko to resign on his own accord, letting the problem linger for seven more months.

However, a change of administration and political dynamics could impact the stability of the Commission. The NRC operates significantly less effectively when there are only three commissioners. An example is the waiting time for a vote increased during mid-2016 to mid-2018 when only three commissioners were on the commission. This is in part because a vote from at least three commissioners is required to act, and one commissioner could withhold their vote (i.e., a “pocket veto”) to avoid action. Pocket vetoes are often used by a single commissioner from a party to block progress for political reasons, and they are becoming more common. A President not nominating replacement Commissioners to avoid a pocket veto situation, or the Senate delaying or blocking nominations to perpetuate gridlock at the NRC is also a political decision.

Congress also has influence through oversight activities. In the past, members of Congress have guided the composition of the Commission and issues such as spent fuel management. Congress can, and has, passed legislation to direct actions at the NRC, or rescind policies of the Commission. For example, Congress forced the NRC to revoke its policy regarding how to regulate risks that are considered to be below regulatory concern.

Concerns of Presidential influence over the NRC are no more or less concerning than Congressional pressure on the Commission. But, this has always been the case and is by design. There need to be checks and balances, and these checks exist at a higher level than the technical work of implementing the NRC’s mission that ensures safety and environmental protection.

Independence and Backstops Within the NRC

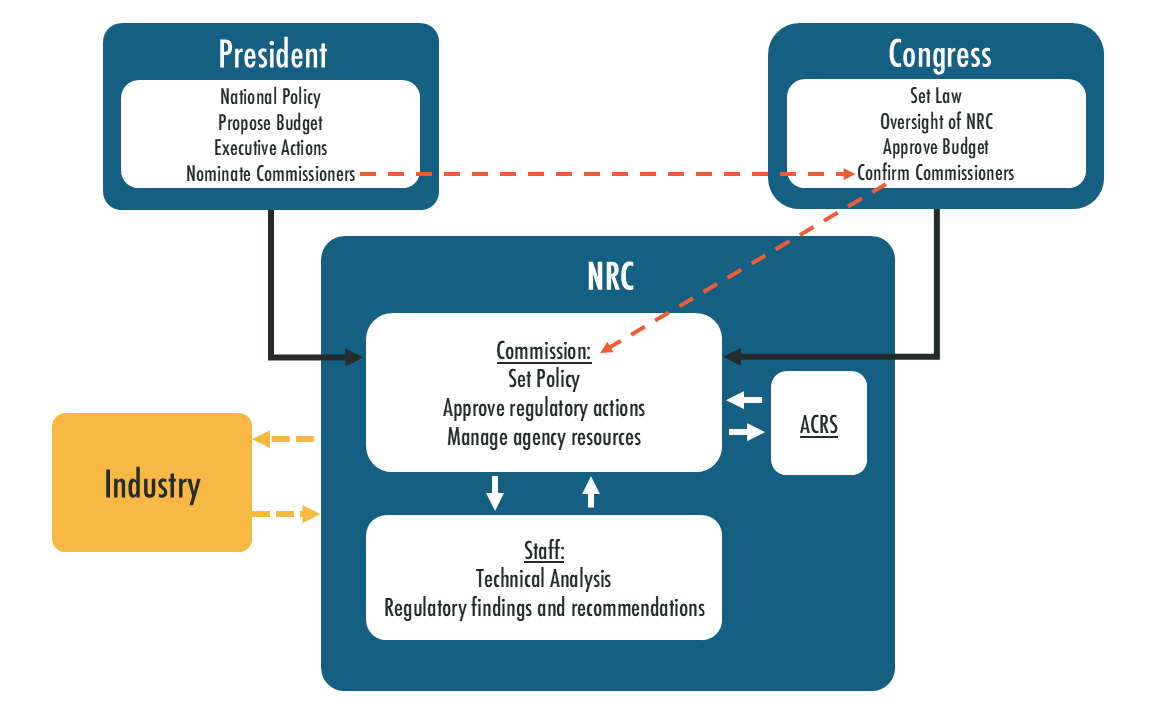

While much of the debate over NRC independence has been in relation to the commission’s independence from Presidential administrations and Congress, there are multiple layers of independence within the agency itself that remain crucial for the NRC to fulfill its statutory obligations. Effectively, the NRC operates through three relatively independent structures: the Commission itself, the NRC staff, and the Advisory Committee on Reactor Safeguards (ACRS), which is a safeguard that checks the technical detail of all licensing decisions.

The NRC staff conducts the safety and environmental evaluations largely independent of the Commission with technical detail and rigor. Depending on the licensing activity, evaluations may be published for public comment or be open to intervention by third parties. Once complete, reports that detail whether the application satisfies the letter of the regulations are sent to the Commission along with the staff’s recommendation.

The Commission then independently reviews the reports, staff recommendations, input from the ACRS, and public comments. The Commission is required to hold a hearing on the licensing actions with the staff and applicant, and ultimately, the Commission has to decide whether to issue the license.

The Commissioners can still put pressure on the staff by overriding the staff recommendations, changing agency policies, or avoiding votes on certain matters for extended periods of time if they do not agree with the staff or options provided by the staff. For example, a 2017 proposed rule on cyber security was ignored for years and finally withdrawn in 2025. The final emergency preparedness rule for advanced reactors waited for the Commission to vote for more than 18 months, and only moved forward with urging from external groups.

There are further protections to ensure staff can make independent recommendations. The AEA clearly defines protections for whistleblowers. For less severe problems, staff can use the differing professional opinion (DPO) system to force a review of safety concerns. The DPO process has been inefficient and can be improved, but it still serves a purpose.

The ACRS functions as an independent Federal Advisory Committee Act committee. The AEA requires the ACRS committee to review all licensing actions and provide an independent recommendation to the Commission. The ACRS operates through public meetings, and the recommendations are publicly available. Its mandate is to advise the Commission on the safety and reliability of reactor designs, license applications, and proposed NRC regulations and guidance. By law, the committee must be composed of recognized experts in engineering, risk assessment, materials science, and related disciplines. The ACRS must review and report on all reactor construction permit applications, operating licenses, license renewals, and significant amendments for civilian nuclear reactors.

Through this structure, the AEA intended the ACRS to function as a standing, technically-focused safeguard that operates separately from NRC staff to ensure an independent technical check on regulatory decisions.

Transparency provides another check on the actions of the agency. Public engagement and acceptance is critical to the NRC’s mission to enable the use of nuclear technology. A perceived loss of independent decisions in favor of political mandates will quickly erode public trust. Acknowledging this, the recent executive order mandated that NRC reforms must also “maintain the United States’ leading reputation for nuclear safety.”

NRC independence must mean more than simply Commissioner independence from undue federal or industry influence. The AEA established layers of independence within the agency that serve to maintain efficient and effective operation. Protecting internal independence of the NRC staff and the ACRS, along with external transparency, remains critical.

Conclusion

NRC independence may be a misnomer. While the Commission has remained independent from the nuclear industry, it has always been at least partially dependent on the politics of the moment—and by design. The AEA and the ERA established the NRC and its predecessor with clear checks and balances from top to bottom, while accepting that shifting presidential administrations and congressional leadership ultimately will play a role in who is on the Commission and what is prioritized.

While it is critical that the NRC remain independent from the industry it regulates, it is equally important that the internal checks and balances—between the commissioners, staff, and ACRS—are also maintained. Ultimately, the focus on and ability to efficiently and effectively achieve the NRC’s mission are the standards that must not be infringed—protecting public health and the environment while enabling the use of nuclear technologies for the benefit of society.