By Matthew L. Wald

A new nuclear project needs a modest-sized piece of land, transmission lines, water, access by road or rail, and earthquake-stable terrain. It needs something else too: public acceptance.

But nuclear plants often draw some unusual reactions. Some reactions are antique reflexes, and some are inversely proportional to the distance from the project. And some give clues about how developers should pick their sites for new projects.

Here are some “not-so-secret secrets” that explain why it’s easier in some places to get the public acceptance needed to build a new reactor. While every greenfield project has its own challenges, avoiding the most common pitfalls can make siting and construction easier.

Old Reactors Have Old Foes

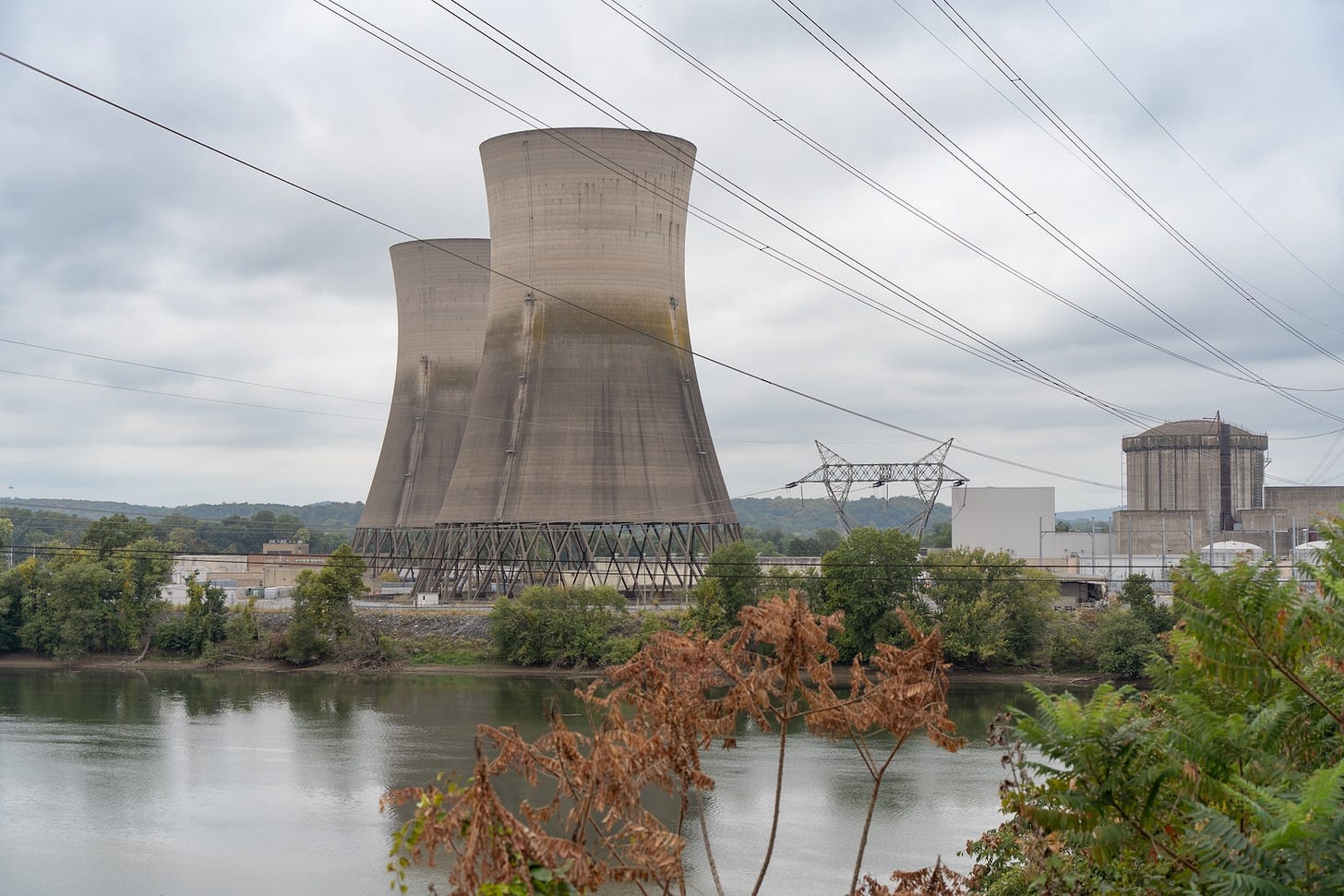

In the antique category, progress towards restarting Unit 1 at Three Mile Island (TMI) near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, has awakened old fears. Opponents are reappearing like 70s rock band stars, grayer and maybe a bit hoarse, but singing the same tunes.

Jane Fonda has tried to re-enter the debate, with an opinion piece in the Philadelphia Inquirer opposing the restart. Fonda’s March 1979 film, China Syndrome, about a fictional accident at a fictional nuclear reactor, probably owes its commercial success to the well-timed TMI accident just twelve days after the movie’s release.

Fonda, who will turn 88 in December, gave a mélange of familiar arguments, including that nuclear power is too slow, too vulnerable to earthquakes, and too expensive. But, restarting Unit 1 at TMI would not encounter any of these issues. The work needed to re-start the reactor, now called the Crane Clean Energy Center, will take a few months, not years. Harrisburg is far away from any faultlines and has negligible earthquake risk. And the restart is budgeted at $1.6 billion, which is dirt cheap for 835 megawatts of round-the-clock power. But the op-ed illustrates the first secret of nuclear siting: if you propose making nuclear energy at an old nuclear energy site, you must deal with the same old opponents who have been fighting that site for years.

The re-emergence of the holdovers is a clue for companies seeking to build new reactors of the kind of reception they will get if they build them adjacent to operating units where there is a history of opposition. Avoiding controversial historical sites can avoid dealing with an opposition that is suspicious of legacy plants no matter how well they have operated, and that fails to see improvements in the technology, advances in safety, and the legitimate benefits to local economies and broader society.

The Small-Radius Halo

A second not-so-secret secret is also apparent in the TMI restart case: that the popularity of a reactor is inversely proportional to the distance. People in adjacent communities, in a circle around the proposed site, may be very supportive. Those at a greater distance—notably, at the state capitol, or in Hollywood—may take the opposite position.

There are myriad other examples of the small-radius halo of nuclear acceptance. When Holtec went looking for a place to put dry casks of nuclear waste in centralized interim storage, two counties in eastern New Mexico, Lea and Eddy, quickly allied to find a piece of land near Carlsbad and facilitate the project. In a region not shy about making a profit from its geology, they welcomed the economic development. But the state legislature in Santa Fe stepped in to prohibit storage of nuclear waste without the state’s consent. The state law was opposed by the city of Carlsbad.

The Texas legislature in Austin took similar steps to block interim storage in West Texas, against the wishes of the local government and community.

Local communities often look at greenfield nuclear projects like manna. They are economic boosters that bring construction jobs and then well-paid, year-round jobs in operating the plant. Regionally, they can reduce energy costs for decades.

Kemmerer, Wyoming, for example, is counting on the TerraPower nuclear project to “save the town,” after the local coal-fired power plant was shut down. The mayor, Bill Thek, told the Washington Post that when the closing of the coal plant was announced, he thought, “we’re going to dry up and blow away.”

In Calhoun County, Texas, where Dow Chemical wants to break ground next year on a high-temperature gas graphite reactor to make steam for industrial use, the county commissioners quickly approved a tax abatement to help the project.

In fact, jurisdictions will squabble over how to share the benefits of a reactor. When Entergy considered building a second reactor at its Grand Gulf site in Port Gibson, Mississippi, and got to the stage of moving dirt to prepare, the state legislature stepped in to grab the money paid by the utility to the government and spread it around the state, rather than let it stay in Claiborne County. There was no opposition to the idea of a second reactor, but the project died as natural gas prices declined.

The More the Merrier

While building a new reactor at a controversial site will elicit further controversy, there is merit to adding an additional unit to a place where a reactor is already operating without drama.

Building next to an operating reactor has some advantages—something Georgia Power realized when it picked the Vogtle site, near Augusta, with two operating reactors, as the place to add twin AP1000 units. The site had already been characterized for earthquakes and floods, and ample weather data was on hand. There is already a security plan, although it may need to be expanded. And when new plants are added to an old site, they can share human resources like instrumentation and control technicians, health physicists, electricians and engineers.

In the case of Vogtle, co-locating the new plants allowed the builders to draw on support from local communities that recalled the prosperity brought by construction of the first two plants in the 1980s.

Many of the plants now running were intended to host multiple reactors. Many have land and water sufficient for more units. And all have access for shipping in large components, and have grid connections.

New Kinds of Reactors Will Need New Kinds of Sites

All these lessons pertain to big reactors of the kind now in service, and modernized versions, like the Westinghouse AP1000 model built at Vogtle, that are under consideration around the country. But a different set of secrets may apply to some advanced reactor technologies.

Micro-reactors, for example, are all likely to be on “greenfield” sites, although the field may not be green; it may be a parking lot with a diesel generator, which makes a noisy, unreliable and smelly neighbor.

The siting decisions will fall to a different set of actors. Some will be corporate, like mining operations that are far from the grid. Others will be remote communities, which now use diesel generators and recognize the difficulties of getting diesel shipped in. In either case, the local benefits to reliability of electric supply and to air quality and noise will be obvious to local communities.

Larger advanced reactors provide benefits that may be more difficult to communicate. For example, they may use fuel forms that are extremely heat-tolerant, or safety systems that are mostly reliant on uninterruptible forces, like gravity and natural heat dissipation. The significance of the engineering details may be somewhat harder for neighbors to grasp.

But they, too, will be welcomed locally, for the clean energy and jobs they provide. They will get some opposition from more distant opponents, who are already arguing, for example, that we should not try to build something that no one has built before. But on that basis, we ought to go back to plants that burn pulverized coal.