The Fall of Permitting Reform

Passing a Permitting Bill Has Never Looked More Plausible, But Hurdles Remain

By Elizabeth McCarthy

Rising energy costs, stalled transmission lines, and clean energy projects under threat of cancellation: The need for permitting reform has never been more apparent. Yet, despite broad agreement that America’s build-out has slowed to a crawl, the political will to act remains elusive. Lawmakers in both parties continue to talk about modernizing our outdated permitting system, and this fall has seen a surge in new bills promising to do just that. But for all the legislative activity, it isn’t obvious that meaningful permitting reform will pass during this Congress. If we’re ever going to move beyond modest, technocratic tweaks, we’ll need to take a hard look at what’s truly necessary to build faster, to ensure credible and effective environmental review, and to get something passed.

The political challenges are well understood at this point. Democrats remain wary of efforts to overhaul the National Environmental Policy Act, a cornerstone of the regulatory system. They worry that narrowing judicial remedies or procedural rules could result in significant environmental harm and silence public input. And in light of partisan acrimony and the Trump administration’s attacks on solar and wind energy, Democrats are nervous that permitting reform initiatives might fail to protect renewable energy, undercutting their climate policy preferences. Meanwhile, Republicans are skeptical of federal efforts to streamline transmission siting and planning, which they view as a backdoor to the wind-and-solar-heavy energy policy ambitions of the Biden administration. And both parties, with some justification on each side, continue to accuse the other of energy tribalism. Despite the momentum behind permitting reform, these sources of skepticism from both parties remain significant barriers to an eventual deal.

Committee dynamics compound these political divides. Two House and two Senate committees share jurisdiction over permitting and must coordinate to get anything through. Each committee prioritizes its interests. No chair can carry a comprehensive deal alone. But coordination efforts across committees are few and difficult. In the Senate, minority Democrats hold considerable negotiating leverage over legislation that emerges from the Environment and Public Works Committee, which has jurisdiction over changes to NEPA. Meanwhile, the Energy and Natural Resources committee controls transmission issues. Any comprehensive deal will require both committees to be aligned and members of both parties to be on board.

The politics and substance of permitting reform have come a long way. Despite a seemingly paralyzed legislature, Congress is full of serious, well-developed ideas for fixing our broken system. The ePermit Act, which would modernize data sharing and digitize environmental reviews, stands out as popular, sensible, and achievable. And the SPEED Act, while flawed, is a disciplined policy proposal, reflecting a growing recognition that NEPA reform can’t simply mean repeal. With the Cheap Energy Act, the SPEED & Reliability Act, and the Fix Our Forests Act, Democrats as well as Republicans have begun to reckon with the depth of the nation’s environmental regulatory problems.

Permitting reform has never looked more plausible. But there remain significant substantive and political hurdles between introduced legislation and a successful, meaningful bipartisan deal. Clearing these hurdles would not only boost the prospects of reform this session, but could ideally initiate a legislative flywheel of regular environmental regulatory reform for Congress to pursue for years to come.

The SPEED Act

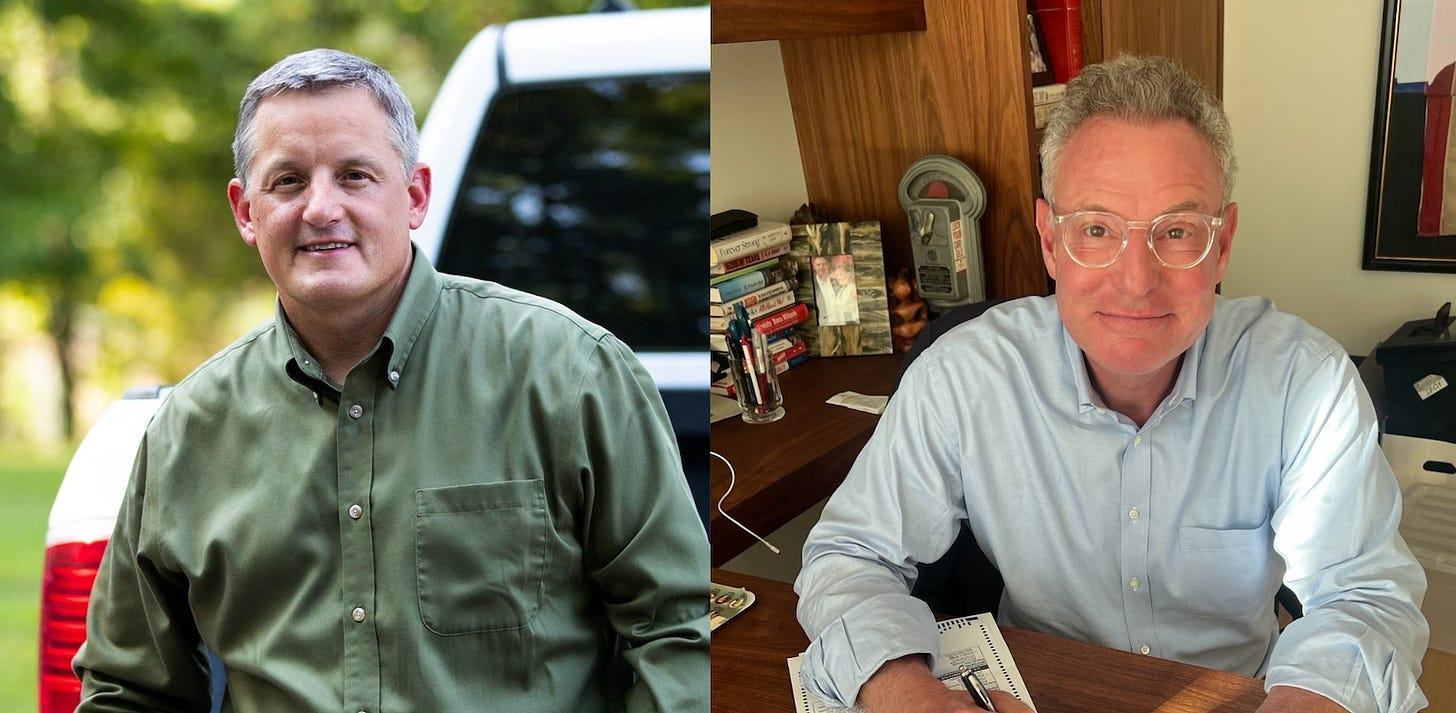

The Standardizing Permitting and Expediting Economic Development (SPEED) Act, introduced by House Natural Resources Chairman Bruce Westerman (R-AR) and Rep. Jared Golden (D-ME), is the most sweeping and talked-about proposal this fall. It correctly identifies the core problems—drawn-out reviews and obstructive litigation—and aims to address them through major changes to judicial review and the environmental review process itself.

These impulses are admirable. But by functionally eliminating how courts can enforce NEPA and loosening requirements agencies must follow, the bill risks weakening the very incentives that make environmental review credible in the first place. By eliminating courts’ ability to stop projects, the SPEED Act would remove the backstop that ensures agencies take their statutory obligations seriously. Without the teeth of enforcement, compliance could become optional, and the quality of review would likely erode. While it’s hard to predict, the consequences would likely extend beyond NEPA itself. Claims under other statutes, like the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act, are often litigated alongside NEPA. Neutering NEPA litigation could push more litigation toward these statutes.

A better approach would preserve a narrow but real role for the courts, enough to keep agencies honest without inviting endless litigation. The discretion SPEED offers to eliminate meaningful review could create a whipsaw of NEPA guidance from administration to administration, creating confusion for the courts and uncertainty for developers.

Successful reform would provide a voice, not a veto, to the public and other stakeholders. It would strengthen the public engagement process, require agencies to seriously consider comments, and then restrict judicial remedies that serve as veto points later in the process. One additional reform that deserves attention, though it’s received less discussion, is consolidating NEPA litigation in a single federal court. Centralized review could create precedent, shorten timelines, and end the inconsistent rulings that slow projects nationwide.

Whatever its merits, SPEED is unlikely to pass the Senate as written. Both the Senate Environment and Public Works (EPW) and the Energy and Natural Resources committees (ENR) are drafting their own visions for permitting reform and do not see SPEED as the starting point. Even though SPEED has Democratic House co-sponsors, its reforms are likely more aggressive than Senate Democrats wielding the filibuster would accept. As of this writing, Chairman Westerman is soliciting potential amendments on the bill. We’ll see how this shifts the dynamics in the ongoing negotiations.

Fix Our Forests Act

The Fix Our Forests Act offers a compelling contrast to SPEED. Reps. Bruce Westerman (R-AR) and Scott Peters (D-CA) introduced FOFA in the House, and Sen. John Curtis (R-UT) introduced it in the Senate with bipartisan co-sponsors including Tim Shelly (R-MT), Alex Padilla (D-CA), and John Hickenlooper (D-CO). FOFA’s judicial reforms strike a sensible balance between cutting down on litigation and doing so in a way that preserves agencies’ incentives to prepare adequate NEPA analyses. Specifically, in the Senate version, FOFA’s judicial reforms limit but don’t eliminate the circumstances under which a court can stop a fireshed management project subject to NEPA. FOFA also forces judges to consider the purpose and likely effectiveness of the project before granting project-stopping relief. And finally, FOFA reduces the timeframe for filing claims covered by the Act from six years to 150 days.

The fact that FOFA’s narrower, carefully negotiated bipartisan package represents the Senate’s ceiling for agreement signals that SPEED’s judicial reforms, which would functionally eliminate courts’ ability to stop projects, go too far to pass the Senate.

While FOFA would be a clear victory for permitting reform if it passes, there are ramifications to advancing it alone. Pulling forest management out of the broader permitting debate risks draining momentum for more comprehensive NEPA reform. Democrats are more comfortable reforming NEPA to address wildfires but reluctant to open bedrock environmental statutes to broader revision. Without forest management as an impetus for NEPA reform, the Democrats’ willingness to engage in broader reform may dwindle. One possible solution would be to expand the judicial review provisions in FOFA to cover a broader set of infrastructure projects outside forestry.

ePermit Act

A bill from Reps. Scott Peters (D-CA) and Dusty Johnson (R-SD), the ePermit Act, focuses on modernizing the administrative process of permitting rather than changing the substance of environmental review laws. Rather than getting caught in partisan debates over statutory reform, the bill finds bipartisan footing in the low-hanging fruit of technology and communications modernization. Updated technology and interagency communications capacity could, without additional reforms, make the current permitting process faster, more transparent, and easier to navigate.

While other bills seek to rewrite NEPA itself, ePermit aims to improve how it works. Standardizing data, improving interagency coordination, and increasing public visibility into project reviews would resolve government-wide inefficiencies while improving transparency and accountability. The ePermit Act could and should pass in something like its current form, almost no matter how the broader permitting negotiations proceed.

The SPEED & Reliability Act

Initially introduced in 2024 and reintroduced this year by Rep. Scott Peters (D-CA) and Andy Barr (R-KY), the SPEED & Reliability Act would update how major transmission lines are approved. The 2025 version keeps the same goal of improving grid reliability but scales back federal authority over siting and cost-sharing in an effort to make the bill more appealing to Republicans. It moves away from the cumbersome National Interest Electric Transmission Corridor (NIETC) process by giving FERC greater permitting authority. But it does not grant the clear, centralized authority that is likely necessary to expedite review and resolve interstate siting conflicts.

Despite bipartisan sponsors, the politics of this bill remain difficult. Expanding federal siting authority has little traction in the current Congress, and Republican hesitation to move meaningfully on transmission leaves few paths forward. Discussions often stop short of significant reform, settling instead on so-called “grid enhancing technologies” (GETs). These upgrades can help utilities squeeze more capacity from existing infrastructure, but they don’t replace the need to build new high-voltage lines. These make the grid smarter, not bigger. Without a broader shared interest in policies that would expand construction and coordination, the SPEED & Reliability Act has little chance of making it to the House floor.

The Cheap Energy Act

The Cheap Energy Act is a statement of Democratic priorities, some of which include permitting. The bill also covers clean energy tax credits, energy efficiency, and other subjects. While the GOP holds Congress, this bill likely won’t see further legislative action this session.

Introduced by Reps. Mike Levin (D-CA) and Sean Casten (D-IL), co-chairs of the SEEC Clean Energy Deployment Task Force, the Act would expand FERC’s authority over transmission and—like the ePermit Act—invest in permitting and data capacity to make the NEPA process more transparent and predictable.

The bill matters less for what it would build than for what it signals. For years, Democrats have centered energy debates on climate goals and belatedly focused on the practical need to make power cheaper. Hence, Democrats made a late shift from “Build Back Better” to the “Inflation Reduction Act” before the law passed in Summer 2022. The Cheap Energy Act marks a clear rhetorical shift toward affordability and reliability; it does not emphasize emissions reductions. Still, much of the bill includes subsidies and spending that echo earlier legislative efforts. With no Republican support and the Senate focused on different approaches to energy policy, this bill serves primarily as a useful if symbolic Democratic signal rather than viable legislation.

The Complete Package

Both parties agree that permitting is too slow and fractured, but they often differ on what fixing it would entail. Republicans want to scale back NEPA and limit lawsuits; Democrats often see those changes as going too far, weakening environmental safeguards and community input. The politics of permitting follow a familiar pattern. It’s easy to tweak the process around the edges, but it’s much harder to change the rules that make it slow in the first place.

On the surface, the ePermit Act appears to fit this pattern. But it should not be misunderstood as a modest reform. It would overhaul the archaic systems of the federal government for implementing NEPA, a vast organizational undertaking. Even still, it probably wouldn’t move as a stand-alone bill. But it could be attached to a must-pass package, possibly the Surface Transportation Board reauthorization, which is due before September 2026.

The Fix Our Forests Act also has a path forward. Its balanced approach to judicial reform shows that it is possible to accelerate projects without delaying environmental review. While passing as a standalone bill could complicate broader reform later, forest permitting is an urgent and achievable step. A large share of NEPA litigation concerns forest management projects. And new research from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory finds that replacing transmission lines and wires after wildfires is one of the most significant factors driving rising energy costs in the American West.

The SPEED Act faces slim odds of reaching cloture in the Senate in its current form. But it has five Democratic co-sponsors and may have the momentum to pass the House. Both Senate committees are drafting their own bill text, which may emerge as wholly new legislation or form the basis for revising SPEED.

To work, SPEED would need to restore a narrow role for courts to keep agencies accountable. It would also need to raise the statutory floor for public comment, facilitating early public engagement that helps agencies and developers avoid challenges to their projects later in the process. SPEED should also codify Seven County with greater fidelity. In Seven County, the Supreme Court gave agencies discretion not to analyze effects “separate in time or place” from the project itself. SPEED tells agencies that may not consider those effects, even if they want to. Lawmakers working on SPEED should consider borrowing from the Fix Our Forest Act, whose judicial review framework strikes a better balance—speeding up approvals without eliminating accountability. Adopting that model would help preserve a narrow but real enforcement backstop that keeps agencies honest without inviting endless litigation.

Markup of the SPEED Act in the House is expected in the coming weeks. Meanwhile, Senate EPW and ENR are both drafting bill language for companion bills, though neither has released text. EPW’s approach is likely to contain elements of Senator Capito’s RESTART Act of 2024, which would have established deadlines for court review and agency NEPA work, among other procedural changes. A successful bipartisan deal would hammer out a consensus on the various judicial review provisions under consideration, ideally one that opens up a compromise space for future reforms to other environmental statutes like the National Historic Preservation Act and the Endangered Species Act.

The politics of permitting reform have advanced considerably in recent years, and they represent an encouraging exception to the hyperpartisan gridlock that characterizes many other issues. Getting the policy details right matters, not only for passing meaningful reforms this Congress, but for compounding the political momentum for years to come.