The Environmentalists Making Forest Fires Worse

And How The Fix Our Forests Act Can Stop Them

By Alex Smith and Elizabeth McCarthy

In early January 2025, simultaneous wildfires tore through Southern California. The Palisades Fire, starting in the Santa Monica mountains above Pacific Palisades and Malibu, covered just over 20,000 acres, destroyed over 6000 structures, and killed at least 12 people. The Eaton Fire started just 40 miles away in the San Gabriel mountains above Altadena and spread to 14,000 acres, burning down 9,400 structures in its path, and killing at least 19 people. Together, the two fires caused over $50 billion in damage.

Due to their extreme human and financial costs, the Eaton and Palisades fires symbolize the scale of the wildfire crisis in California. From 2010 to 2024, California endured more than 8000 wildfires a year that burned on average just under 1.1 million acres of land. In total, over that period, more than 16 million acres burned in California—about 16 percent of the total landmass of the state. These fires burned through endangered species’ habitats, killing millions of wild animals, and threatening endangerment of species like the long-toed salamander and dozens more.

The smoke produced by California’s fires also costs lives. Between 2008 and 2018, PM2.5 pollution from wildfires was responsible for between 52,480 and 55,710 premature deaths in California alone. But the smoke from California’s fires does not stop at the state border. In 2020, about 28,000 premature deaths were attributable to wildfire smoke across the United States, with the majority occurring in western States.

To combat wildfires before they happen, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), county conservation boards, and other stakeholders implement fuels reduction projects that can reduce excess dry wood and shrubs, and clear smaller vegetation that allows fires to grow faster and reach into the canopy of forests. Fuels reduction approaches like mechanical thinning and prescribed burns have proven to be effective mitigation strategies to reduce the damage from wildfires on ecosystems and to help firefighters stop fires. Yet, a small but loud environmentalist minority opposes fuels reduction, instead claiming that California’s forests must be left untouched. They use outdated environmental laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Endangered Species Act, Federal Land Policy and Management Act, and National Forest Management Act in courts to delay, and sometimes cancel, projects that would mitigate the wildfires that destroy the ecosystems they claim to protect, and threaten tens of thousands of lives.

During the period that about a sixth of California’s forests were going up in flames, one single group was busy suing the USFS 24 times. That group, Conservation Congress, was responsible for just under two fifths of the USFS’s NEPA-related lawsuits that were decided in federal circuit or appeals courts in California from 2010 to 2024, and spent $2 million on those lawsuits and 5 more in other western States.

What’s most remarkable about Conservation Congress is not their ability to single-handedly hamstring dozens of USFS projects, but that they are, in fact, single-handed: the organization effectively is just one person: Denise Boggs of Great Falls, Montana.

A long-time forest activist and veteran of the California “timber wars,” Boggs has taken the USFS to the mat on countless occasions, often coming up the loser. But she is determined. Boggs believes that the USFS, in bed with logging companies, is using fuels reduction programs and other fire management to create “loopholes big enough to drive logging trucks through.” It is Bogg’s mission to close those loopholes and save the northern spotted owl.

But the problem here is not Boggs, per se. The problem lies in a system that allows a single person to make decisions that reverberate and impact millions of people and millions of acres of our natural resources and ecosystems. Boggs may seem like an outlier—few individuals might have as large an impact on forest permitting, or any other form of NEPA litigation—but the fact that U.S. environmental law can allow for such undemocratic processes and excesses is indicative of the system’s inability to rationally protect the environment.

The Tyranny of the Non-Profits

In fact, Conservation Congress is not an outlier. There are plenty of organizations that wield outsized, undemocratic influence over how the federal government can act. From 2010-2024, the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD)—an organization based in Tucson, Arizona with just over a $30 million budget and more than 100 staff members—and the Sierra Club—based in Oakland, California with a budget over $170 million and more than 700 staff members—were responsible for a quarter of all NEPA-related litigation decided in district and appellate courts. These groups are large and well-funded, able to spend millions of dollars litigating projects while simultaneously lobbying federal agencies in Washington, D.C.

When looking at forest management, specifically, groups like Conservation Congress—few employees, with smaller budgets, but with the capacity to delay or outright stop important projects—stand out. Alliance for the Wild Rockies—an organization with few employees and variable funding that sits well below half a million dollars per year—filed 84 suits against forest management projects from 2010 to 2024, or roughly 27% of all forest management NEPA cases in that period. Native Ecosystems Council—similarly small in staff and budget—filed another 53 suits. Collectively, these three organizations were responsible for just over half of all forest management suits during that period.

These are, by definition, special interest groups. The Center for Biological Diversity and the Sierra Club are national non-profits that advocate for and act on behalf of a specific ideological framework that places the abstract entity of “the environment” over all else. While the Sierra Club has a much longer history—the organization was founded in 1892 by legendary environmentalist and conservationist John Muir—the rest of these non-profits are relatively new projects. CBD was founded in the 1990s by a group of northern spotted owl biologists who sought to protect the species at all costs. Conservation Congress, Alliance for the Wild Rockies, and Native Ecosystems Council are all post-turn-of-the-21st-century organizations founded by activists who grew up—ideologically speaking—during the environmental protests of the late 20th century. With the exception of the Sierra Club, which has grown beyond just conservation and preservation, these groups are single-issue groups—protect endangered species, no matter their niche, or lack thereof, and ignore everything else.

Through NEPA litigation, these groups are able to wield outsized power, and curb federal projects—which often have support from local stakeholders—in the name of protecting toads, owls, and more. Their litigation delays, and, in some cases, forces agencies to cancel, projects that would have serious benefits, without even the semblance of a democratic process. The USFS, on the other hand, at least has democratic oversight from elected officials at the federal level. And the local groups working with the federal agency—like county conservation districts, municipal works programs, and more—are directed by elected officials put into office by local elections.

Who agreed to let Denise Boggs, Michael Garrity of Alliance for the Wild Rockies, and Sara Johnson of Native Ecosystems Council decide how our forests should be managed, what species are preserved over others, and what works or does not work when it comes to fire management?

Fire Management

That NEPA provides an undemocratic pathway for single-issue groups to derail federal government projects is bad enough. What makes it worse is that the single-issue groups that currently take advantage of that system are fundamentally wrong about how forests ought to be managed.

Ultimately, groups like Conservation Congress don’t really claim that fire prevention through mechanical thinning and prescribed burns—or other fuels management practices—are not effective. Boggs simply argues that any and all U.S. Forest Service projects are secretly logging projects. Fire management, to these groups, is a cover-up for a corrupt federal agency in bed with timber companies. To save old-growth forests, they must stop all projects all the time, and forests must go untouched.

But, letting forests go untouched is a prescription for more and worse forest fires—the kind that produce toxic smoke, and destroy the wild landscapes that activists claim to protect. While some of the environmentalists opposed to fire management programs might argue that forest fires are a natural part of forested ecosystems, they ignore the fact that 21st century American forests are completely unnatural. During the majority of the 20th century, the USFS and young American communities in the western U.S. understood fires as a threat to livelihoods, and stamped them out early and often. This fire-suppression led to the overgrowth of trees, brush, and other fuels.

Fuel overgrowth not only makes forest fires grow faster over a forested area, but it also makes them burn more in their path. Densely packed vegetation allows for the fire to reach tree canopies that would otherwise remain untouched, creating sweeping destruction over an entire forest rather than simply burning out the smaller, more fire-intolerant species. These more catastrophic types of fires are called “stand-replacing” fires.

After more than a century of fire-suppression, California’s forests are no more “natural” than a suburb. Whereas naturally-occurring fires could burn through forested areas without complete devastation in the 19th century and before, in the 21st century, fires represent a catastrophic risk to both the forest ecosystem and to human populations up to hundreds of miles away.

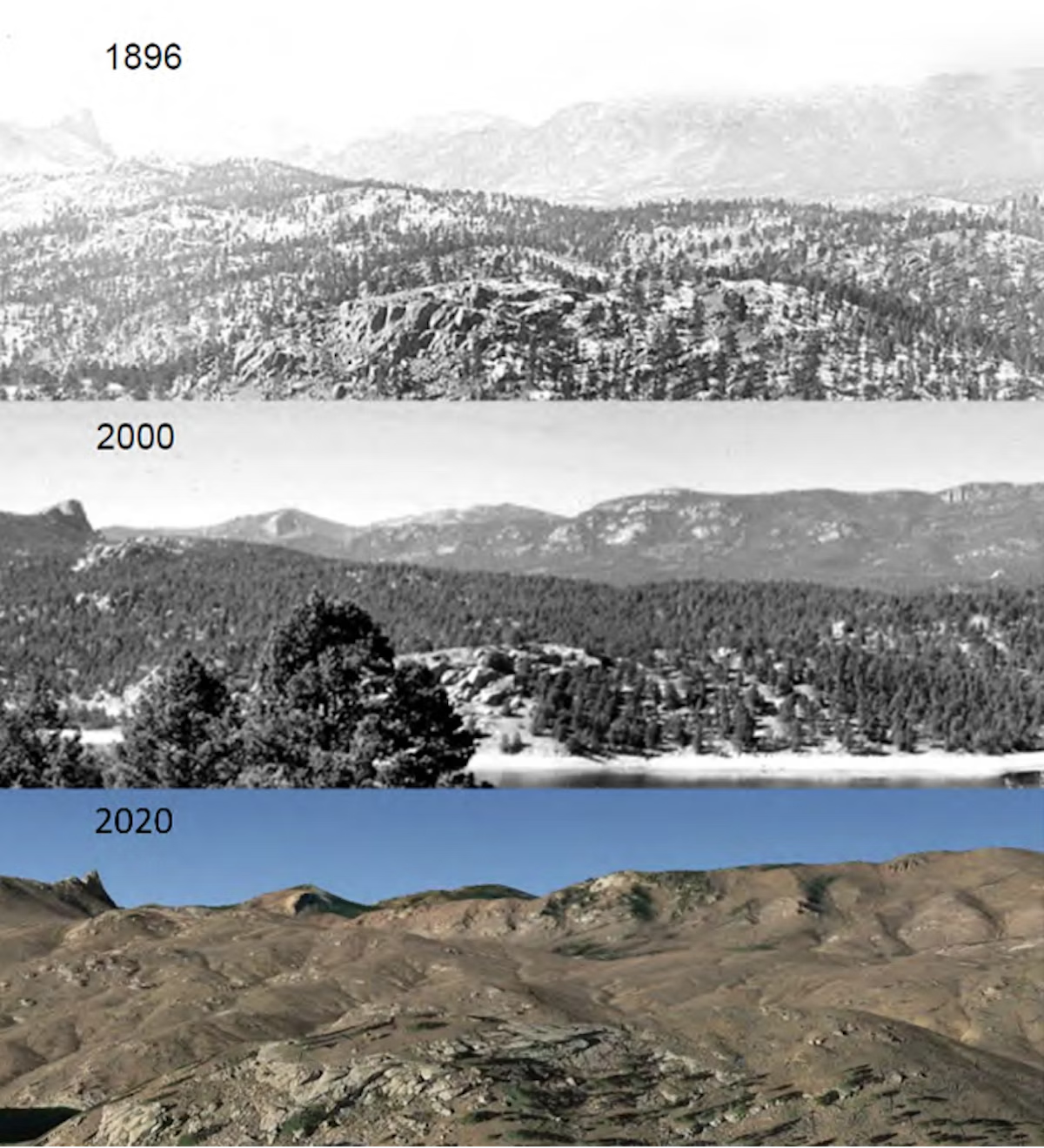

The image below shows the result of a fire suppression policy over the 20th century, and the resulting devastation once a fire does burn through the area.

Avoiding stand-replacing fires and reducing the damage caused by wildfires requires proactive forest treatment. The combination of mechanical thinning—removing excess vegetation—and prescribed burning—intentional, controlled fires that clear the forest floor—have been proven to dramatically reduce the speed with which wildfires grow and to protect the larger trees that make up a forest stand.

The value of combined thinning and prescribed burns can be observed empirically, too. The Bootleg Fire, which occurred in the summer of 2021, burned over 400 thousand acres of southern Oregon. Some of the fire burned through areas that had received no treatment from the USFS or local forest managers, areas that had just been mechanically thinned, and areas in which managers conducted both thinning and prescribed burns to remove excess fuel. The image below shows the real-world result:

While areas that received no proactive treatment were destroyed by the fire, the areas that received any fuels reduction fared far better, and the areas that had previously been thinned and burned by forest managers saw dramatically less damage to mature trees.

While forest conservationists would be correct to assert that managing forests simply by logging them for timber would also exacerbate wildfire risk, their attempts to limit the USFS from doing any proactive fire management leaves America’s western forests with high fuel quantities and an increased risk of fast-spreading, stand-replacing fires.

Fix Our Forests

Thankfully, legislators have begun to recognize that the environmental laws of the 20th century restrict the federal government from managing the forests of the 21st century. The Fix Our Forests Act (FOFA) represents the first serious legislative attempt to address the procedural delay that has prevented effective wildfire prevention and forest stewardship. FOFA aims to streamline environmental reviews and cut red tape so that forest management can proactively avoid disastrous fires.

Under FOFA’s “fireshed management” framework, the federal government no longer would need to treat every prescribed burn or thinning project as an isolated event. Instead, the proposed Wildfire Intelligence Center would map “firesheds”—landscape-scale zones with similar wildfire risk—and compile them into a digital Fireshed Registry. This would allow agencies to identify priority regions where proactive thinning, prescribed burns, and restoration projects can move forward quickly, guided by data rather than litigation.

Unlike the narrow exemptions currently in place under the Healthy Forests Restoration Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, once a fireshed is designated as high risk, streamlining reviews would become mandatory. Projects that meet the scientific criteria for fuels reduction or restoration must proceed under an expedited process, rather than entering the traditional, multi-year NEPA review. This would turn risk identification into an obligation to act, ending the bureaucratic hesitation that leads to delay.

Within those identified firesheds, the Act would expand the use of categorical exclusions under NEPA, to projects up to 10,000 acres. Had this standard been in place a decade earlier, the Smokey Project—a 7,000-acre fuels-reduction effort in the Mendocino National Forest—would likely have qualified. This would have likely avoided nearly a decade of litigation between Conservation Congress and the USFS that delayed the project until after the August Complex Fire burned through the untreated area in 2020.

Equally important, FOFA reforms the rules that have allowed a handful of activist litigants to hold entire regions hostage through procedural lawsuits. It would limit the window for legal challenges to 150 days, require courts to weigh the ecological risk of delay, and allow agencies 180 days to correct procedural errors rather than being stopped and then forced to start from scratch.

The pace of the crisis had outstripped the pace of institutions. The Fix Our Forests Act is an attempt to bring those institutions up to speed by making environmental laws work—allowing agencies to fast-track critical projects and avoid the paralysis created by litigation.

Beyond the Timber Wars

We at Breakthrough have argued for years that climate change can not be solved using the environmental policies of the late 20th century. While lead in groundwater, ozone pollution, and many other environmental crises of the second half of the 1900s could be legislated away with restrictive policies, curbing CO2 emissions and reducing anthropogenic global warming can not be done through carbon taxes, rote emissions restrictions, and other analogous policies. What is left of the climate movement has begrudgingly come to terms with this. Instead of carbon taxes, environmentalists are now arguing for infinite subsidies, innovation policy, and industrial strategies to develop and build clean energy and other carbon-free technologies.

The same is true for forests. The environmentalist logic of the 1990s (and earlier), born within the context of runaway logging companies and clear-cutting, simply does not work to help mitigate wildfires and properly manage America’s forests in 2025. The veterans of the timber wars can be given credit for fighting what was once a “good fight.” But they are still trying to fight the last war.

In America all important decisions are made by lawyers in front of Administrative Law Judges. These mercenary armies of lawyers argue for "stakeholders", and technically trained people are not in the room, except when called upon. What's the point of having an executive or Forestry expert when their only power is to hire lawyers?

The way, the Public and "The Environment" are not "Stakeholders".

Administrative Law Judges are also partly to blame here. They could help a lot if they re-established the rule of law by throwing out these SLAPP suits directed at public officials doing their jobs. In the 1960's these anti-democratic destructive lawsuits would be thrown out. For many reasons such as "The litigants lack standing. They are coercive and uninformed." Back then executives of independent agencies like the Forest Service were entrusted with executive power, and used it. It wasn't perfect. We witnessed travesties like the uneconomic rapid decimation of almost all of California's Redwood Forests in anticipation of the establishment of the protective parks.

Today's variant of the Supreme Court has moved to curb the power of independent agencies, using apparent mismanagement as an excuse. Not helping!

Administrative Law courts demonstrate poor critical thinking skills, in particular lawyers downplay numeracy, as they aren't trained in arithmetic. They can't tell the difference between big problems and little ones. They can't prioritize various interests. It's valuable that lawyers prevent bad things from happening, but they also prevent good things. Stalemate is not a solution.

Today we live in the Anthropocene Epoch. That means that Earth is under Human Control. We don't control ourselves very well, but we certainly control the climate more than "natural" variations. Humans move more Earth than Geology. Humans and our domesticated animals make up almost all the vertebrate animals on Earth.

The old environmentalists believe that what Nature really needs is neglect. Just leave it alone. That ideology is a misunderstanding based in anti-Indian racism. America was never neglected. Our Amerindian ancestors cultivated our lands. Burned pasture for the Elk. Burned forests too. Protected the Salmon runs. Respected the Bears and Wolves and Coyotes at some cost. Amerindians had the capacity to exterminate dangerous predators, as much as the European immigrants did. But without the interest in keeping penned defenseless domesticated animals they made a wiser choice.

There used to be amazing wildlife in the lakes and ponds in Yosemite. But once the Indians were chased off and the Park management neglected it, they have dried up and the biodiversity is gone. And the park management says "It's just nature taking its course'.

Nature should not be what's left after the Indians are chased away. You want biodiversity, maybe consider hiring some Indians to use traditional practices. (Including prescribed burns.)

With dominance comes responsibility. Understanding and protecting biodiversity requires informed action. As it always has. Amerindians did a pretty good job building America's soil and "wild" habitats for thousands of years. We should measure ourselves to their mark.

Great article Elizabeth! I'm a naturalist/beekeeper living in the California Gold Country, where all the trees were cut down during the Gold Rush. They've since been replaced by 2nd-growth forests misguidedly "managed" to completely prevent even small wildfires.

We're now surrounded by crowded, over-vegetated, fuel-heavy tinderboxes just waiting for a spark. The resulting crown fires are so intense that firefighters jare forced to just "stand back" and watch them burn. Glowing embers the size of silver dollars fall miles downwind.

What's equally bad is that such crowded forests are not as ecologically diverse as those that are allowed to periodically burn, after which our fire-adapted vegetation quickly regenerates, leaving a nice balance of mature trees, but allowing enough sunlight to hit the ground for a diversity of plant and animal species to thrive in between the trees.