Mining Is Not What it Used to Be

U.S. mining doesn’t need fixing to help the world decarbonize

By Peter Cook and Seaver Wang

In the United States, mines face a gauntlet of scrutiny that starts well before workers break ground and doesn’t end until the day the mine closes. Regulators scour blueprints during the permitting process for risks like potential tailings pond leaks. State environmental agencies track drilling reports to ensure crews properly cement their drill holes to protect local groundwater. Meanwhile, miners maintain safe excavation, ventilation, and illumination practices in anticipation of random safety checks by a federal inspector. Yet, most regular citizens rarely think about mining and remain wholly unaware of such day-to-day procedures. This means that when most people do think about mining, they automatically imagine it as a nasty business to be avoided at all costs.

Imaginations can easily run wild without much knowledge of how mining works. At the extreme end, members of the Deep Green Resistance group convinced that “clean energy is a myth” occupied the site slated for the Thacker Pass lithium mine in Nevada before agencies could even finish the project’s environmental reviews. Passing muster, the project later received the last of its permits and will eventually produce enough lithium to supply 800,000 electric vehicles each year. More typically, even devoted clean energy advocate and veteran podcaster David Roberts—on an episode devoted to responsible mining no less—seemed content to describe mining repeatedly as “gross”, “unpleasant”, “grim”, and “rapacious,” with a “terrible record”, hardly reassuring listeners over how clean technology companies source their minerals.

Environmental non-profits seize on such automatic negative sentiment to help mobilize maximum public opposition to mine projects. For example, environmental organizations systematically mischaracterize the U.S. mining industry as governed by the ancient and permissive General Mining Law of 1872, lamenting the current status quo as giving industry free license to pillage federal land. But this selective narrative conveniently and deliberately omits the long list of U.S. laws that have since followed the General Mining Law, which form a substantial body of standards and regulations that govern the mining sector as it exists today in reality. Indeed, the U.S. currently boasts some of the most stringent and comprehensive regulatory safeguards for mining in the world.

Failing to recognize how mining practices and oversight have improved perpetuates needless resistance to new mines and inhibits the acquisition of the raw materials that supply modern society, and enables low carbon energy technologies like electric vehicles and solar panels.

From pickaxes to world-class operations

It may surprise those who turn up their noses at the idea of a mine that the world-class regulatory framework the U.S. boasts has governed mining operations for over a half century. Laws like the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960 and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 codify the role of land management agencies in minimizing a mine’s impact on public lands. Other laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act ensure that mine operations do not introduce harmful levels of materials into the surrounding environment by establishing discharge limits. Ultimately, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 enforces all relevant standards and regulations through the permitting process by requiring agencies to conduct extensive reviews of mine plans before operations begin and to stop projects should designs fall out of compliance.

Originally, the General Mining Law imposed regulations that promoted the orderly use of public land to facilitate mining, such as preventing squatting and ensuring that one miner’s waste pile did not prevent another miner from working a deposit. As Congress introduced new laws, miners have improved their practices further. After the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966, for example, agencies began assessing proposed mining areas for historical artifacts to avoid needless destruction of cultural resources as miners designed their operations. Miners similarly began avoiding critical habitats designated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service after the passage of the Endangered Species Act in 1973. From a regulatory perspective, a mine in the early 1960s was no different than one in the old west. A mine today, on the other hand, must uphold all of the protections that the long history of environmental laws issued over the last half century have secured.

Even after agencies complete extensive reviews and issue permits, miners continue to employ best practices to keep operations safe and in compliance throughout the lifetime of the mine. Simple measures such as water spray or collection systems limit fugitive dust that could otherwise drift into nearby communities, holding dust concentrations at mills to below 10% opacity (i.e., the degree to which particulate matter obscures visibility). For water, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System requires miners to test runoff to keep discharges at safe levels such as below 1 milligram per liter of arsenic or 0.1 milligram per liter of cadmium—5 and 10 times lower than the Environmental Protection Agency’s cutoffs to qualify as hazardous waste, respectively. Ore that contains sulfide minerals poses the added risk of forming acid mine drainage which can produce runoff with a pH of 2 or lower should exposed rock excessively oxidize. Miners minimize this potential with techniques like flooding old workings, applying special coatings to rock walls, or introducing bactericides to process waters to maintain the pH between 6 and 9.

While tailings dam failures have historically caused major disasters and loss of life, few celebrate that failure rates have generally declined across the globe. In the U.S., Canada, and Europe, tailings dam failure rates since 2000 have decreased dramatically. In the United States, for example, the failure rate for upstream, centerline, and downstream dams—accounting for 80% of all tailings dams in the U.S.—has fallen to virtually zero since 2000, decreasing from 4.4%, 7.9%, and 4.1% to 0.2%, 0%, and 0% respectively. Much of this owes to engineering advancements. For instance, miners have moved from using water dam designs to developing approaches appropriate for tailings-specific considerations like the presence of sediment and the need to periodically raise dam levels. Increased adoption of impermeable synthetic membranes since the 1970s and the practice of dewatering tailings (“dry stacking”) before impoundment has benefitted both dam stability and environmental impact by reducing leakage. Technology has also allowed miners to adjust designs and preempt failures with monitoring equipment including satellites, LIDAR, and fiber optic cables that can detect ground and movement.

Safeguards extend past the mine site to the processing facilities that smelt and refine ore into usable metals. Smelters must adhere to National Ambient Air Quality Standards and National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants to limit emissions of pollutants like ozone, carbon dioxide, and particulate matter. Industry has made great strides on this front by adapting facility technologies. The Kennecott Utah Copper smelter that services the Bingham Canyon mine led on this front in the 1990s to greatly reduce sulfur dioxide emissions—which contribute to acid rain formation—with Finnish flash techniques that avoid open-air processes like transferring molten material in ladles. After the facility upgrades, the Kennecott smelter captured 99.9% of the emitted sulfur.

Mine remediation requirements arguably represent the most stark, tangible improvement to how mining impacts the general public. The Federal Land Policy and Management Act mandated that regulators prevent “unnecessary or undue degradation” when permitting operations on federal land. For miners, this means cleaning up their site once they close up shop.

Remediating project sites tasks miners with returning the land to an environmentally productive state that aligns with agencies’ resource management plans. Here miners backfill pits and regrade sites to recreate original topography as much as feasible. Replacing topsoil—often even using the original material set aside during initial construction—helps miners revegetate the landscape and restore ecological habitats while erosion control measures prevent debris from accumulating in nearby water systems. Dewatering tailings ponds and treating effluent with measures like applying lime to neutralize acids minimizes the potential for harmful runoff. All throughout, agencies hold financial guarantees posted by miners until they finish the job. The Flambeau mine pictured below offers a prime example of the end product of the extensive remediation work miners perform.

We should let the permitting and review process work

The U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management finalized remediation requirements in 1974 and 1981, respectively. Certainly, these requirements have not been able to address the roughly 500,000 older abandoned hardrock mine sites spanning from the pickaxe days to the 1960s that continue to await cleanup today. An understandable degree of distrust of mining for many environmentalists arguably stems from such past traumas, such as the announcement of a mine years ago that would eventually scar the landscape around them. The federal government has a responsibility to clean up these abandoned mine sites, and such cleanup efforts are important for the minerals sector to continue to earn public trust.

At the same time, when it comes to new mines subject to extensive standards, people’s distrust of mining often goes beyond healthy skepticism and leads to reflexive backlash that needlessly and tangibly slows down decarbonization efforts. As a prime example, the proposed Twin Metals Minnesota mine could provide one of the few domestic sources of nickel and cobalt used in batteries and wind turbines. Yet, the Biden administration canceled the project in 2022 during its environmental review in response to environmentalists sounding the alarm over potential impacts to the local watershed. Paranoia had blinded the environmentalists so much that they showed little interest in waiting for the results of the environmental review, which would determine the project’s actual environmental risks, calling instead for a blanket regional mining ban.

Good environmental accountability does not look like NGOs distrusting a project’s public sector environmental review to the point that activists intervene before letting agencies complete their assessments. The National Environmental Policy Act not only mandates such reviews for mines on public land, but ensures that regulators inform the public about a proposed project and consider input on potential risks that agencies may have overlooked. Often, government, industry, and local communities can work together to find ways to move forward constructively on projects. The Thacker Pass lithium project mentioned earlier faced a lawsuit claiming that the Nevada state engineer failed to consider the effects that groundwater consumption would have on a local rancher after the mine altered its initial pumping location. The state reviewed the claim and reached a settlement with the rancher after determining that pumping would not harm their operation.

Mine worker safety is the poster child of how mining has improved

Concerns raised in public comments and during town halls focusing on harm to the local environment and public rarely discuss labor conditions even though the mine worker inherently faces the greatest risk from any onsite pollution or hazard. This leaves underdiscussed the great strides in safety regulations that have taken mining from an every man for himself environment to a stringent labor-centric industry. Most notably, the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977 created the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), which acts as a watchdog that can fine or halt operations for safety violations, and provides concerned workers with a protected outlet to blow the whistle on substandard conduct.

Under MSHA’s watchful eye, all miners must take an extensive safety training course before starting work. Once complete, a miner will know not to enter a heading without proper ground control-measures that now include extensive screening and bolting to prevent cave-ins. Remote-operated equipment like survey drones can even remove the need to send miners into the most dangerous locations entirely. Miners will learn emergency evacuation routes and how to seek refuge in emergency shelters to await highly trained mine rescue teams whose existence is mandated by regulations. Here too technology has helped by equipping miners with locators so that rescuers waste no time.

Labor protections don’t stop at training and major incident prevention. Occupational health standards help protect miners from hazards they face on a daily basis that most ordinary people only rarely encounter throughout their lives. MSHA, for instance, requires hearing protection and sets noise exposure limits to an 8-hour average of no more than 90 decibels that can never instantaneously exceed 115 decibels. Silica dust also poses a health risk that miners limit with preventative measures like masks, ventilation, and enclosed equipment cabs. MSHA began rulemakings in 2024 to further cut the silica dust exposure limit in half from its 1974 value to 50 micrograms per liter, representing a continued commitment to monitor and improve the health and safety of U.S. miners.

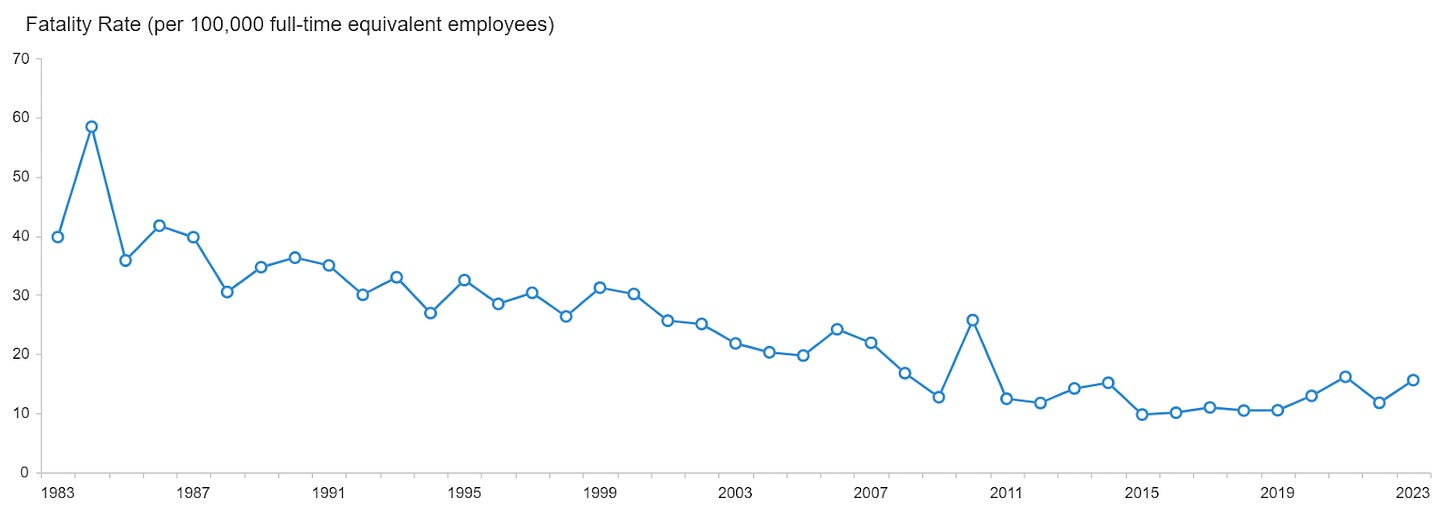

Miners will tell you that safety regulations are written in blood. Many point to the Sunshine mine disaster in 1972 that saw 91 lives lost as the final straw that triggered modern day reforms. At the head of these safety reforms stand America’s industrial labor unions, which themselves provide another bulwark of accountability relative to what workers a century ago or elsewhere in the world could count on. Lessons learned from past tragedies have sublimated into lives saved. In the early 1980s, industry saw fatality rates in the range of 40 deaths for every 100,000 miners. While even a single death remains too many, fatality rates have dropped dramatically since regulations took hold and since safety consciousness spread throughout worker culture, with industry having reduced fatality rates to 10 deaths for every 100,000 miners.

Ignorance has its consequences

Misconceptions of the mining industry and ignorance of all of these safeguards have led policymakers to take the stance that we must fundamentally fix and reform the whole mining sector and dramatically strengthen protections before accepting mining’s role in decarbonization. While an individual project may proceed despite the odd protest group or successfully defend its permits in court, additional restrictions at the statutory or regulatory level without a sound basis would seriously limit our ability to source the necessary mineral supplies at a national scale.

Take exploratory drilling, for example. Federal agencies effectively manage drilling operations without requiring miners to obtain permits because drilling often involves only low-impact activities like leveling ground for drill rigs to work on. Environmental organizations paint these operations as an unregulated free-for-all or an attempt at secretly starting a mine. In reality, miners must notify agencies of their drilling and reclamation plans before starting work, and agencies do intervene should plans involve more impactful activities that require environmental reviews, such as suction dredging, large excavations, or expansive work areas (i.e., more than 5 acres). As drilling continues, state environmental departments monitor drilling reports to ensure that miners properly cement their holes to protect local groundwater.

Nevertheless, environmental organizations urged the passage of the Clean Energy Minerals Reform Act of 2022 (reintroduced in 2023 and 2025) which would require all drilling to obtain permits regardless of the type of activity. This extra red tape would needlessly slow mineral development by forcing agencies to conduct tedious reviews for routine operations they already know cause little impact. The Senate version of the bill went further by proposing to allow agencies the discretion to halt any type of mining activity if it caused “substantial irreparable harm.” The bill left the term so vaguely defined that agencies could block projects based on benign actions like constructing a core shed.

Proposals like these do nothing to raise actual environmental protections and only seek to place enough control in the hands of regulators so that they can shutter projects at the first glimpse of public backlash. In other words, just like the Biden administration’s canceling of the Twin Metals Minnesota project, regulators could make the decision of whether or not a mine should proceed based on misinformed public opinion and for short-term political gains.

While protesters have harassed projects for decades with the fiction that mining is dangerously unregulated, little talk of new environmental protections took place in Congress until policymakers began calling for more domestic critical minerals production. Mining does not need self-flagellating, head-to-toe reform before policymakers can consider policy support measures to source new mineral supplies used in clean energy technologies. Society tacitly accepts mining on a daily basis by using the technology it fuels. Any worthwhile improvements to mining regulations can occur in real time and alongside supportive industrial policy measures. Environmentalists often point to provisions in the General Mining Law that allow mining companies to purchase federal land if they are actively mining them (“claim patenting”). Measures to, say, increase the efficiency of federal permitting processes could easily go hand-in-hand with a proposal to outlaw claim patenting. But such compromises would require accepting that rules-abiding mine projects deserve a pathway to move forwards.

In this political moment, decarbonization efforts require policy efforts to improve the efficiency of mining regulations while maintaining strong environmental protections. Related discussions of ways to streamline regulatory processes to this end have generated proposals like the Mining Regulatory Clarity Act which would speed permitting by allowing miners to alter their mine plans more flexibly, including in response to concerns raised during environmental reviews. Nuanced revisions like this do not encroach on the cornerstone protections offered by the National Environmental Policy Act or Clean Water Act—statutes which policymakers should certainly maintain when looking for opportunities to improve regulatory efficiency.

Failing to appreciate the recent history of achievements in mining safety and environmental protection not only perpetuates a misconception of mining as a smash-and-grab industry but risks missing opportunities to diversify critical minerals production and support key industries like battery manufacturing and semiconductor materials production. Expanding mine production sufficiently to alleviate import dependence and supply strategic sectors involves overcoming obstacles like long construction lead times and debilitating swings in commodity prices that can easily shutter operations. Arbitrary, reflexive resistance to mining based on generalizations about a bygone rules-free era only makes such efforts harder.

US mining does need fixing. The problem is over-regulation, forcing mine closures, and making us dependent on foreign sources. The most obvious examples are thorium and rare earths.