By Ted Nordhaus and Alex Smith

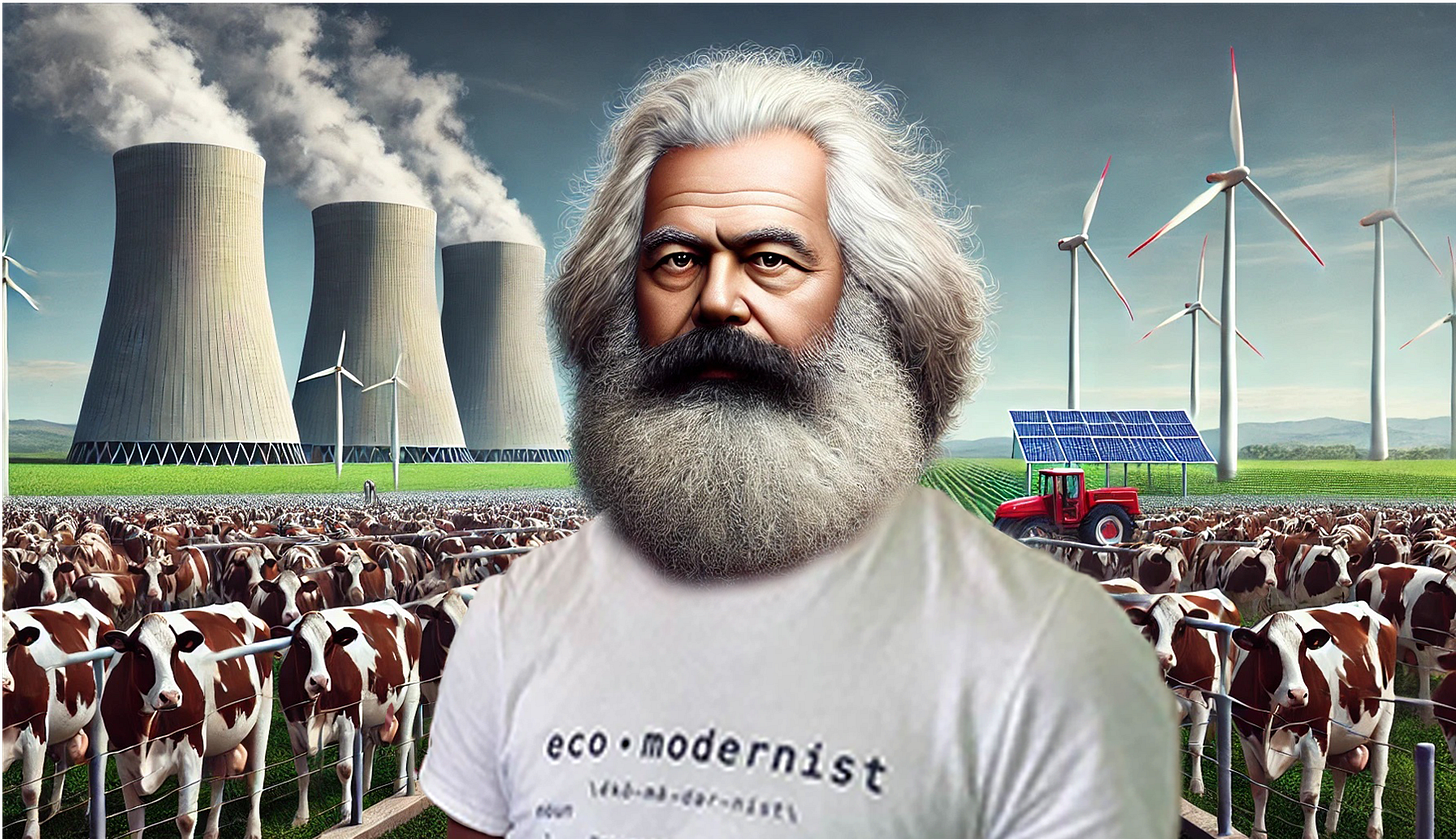

In Part I of this series, we described the conquest of the old materialist Left in the post-war era. In Part II, we break down how the effort to transform Marx from modernization theorist to degrowther presaged broader center-left political debates about capitalism, biophysical limits to human aspirations, and the nature of social, political, and economic modernization. In Part III, we offer a very different reading of Marx. Were he alive today, he would almost certainly be an ecomodernist, not a degrowther, ecological economist, and perhaps not even a communist.

Beyond Marx’s very limited writing about agriculture and even more limited discussion of metabolism, the effort to recast Marx as an ecological thinker and opponent of modernity requires a willful disregard for Marx’s broader theory of history. Marx was, arguably, the first modernization theorist. Without moving much of the population off of the land and into cities, and out of agriculture and into industry, there could be no proletariat. The metabolic rift, such as it was, was an inevitable result of this process. Without it, there could be no capital accumulation, no large working class, no rationalization of commodities and production such that workers might seize control of it.

Both capitalism and the metabolic rift are necessary stages of human development for Marx. Without them, there is no history, only feudalism. Post-capitalism, in other words, is not possible without capitalism, and not in a perfunctory way. Capitalism’s dynamism and productivism is necessary to rationalize and reorganize productive forces. Only once that has happened can the working class, liberated from the land and the feudal social and economic arrangements associated with agrarian life, become a revolutionary force.

In fact, the history of revolutionary Marxist regimes, in Russia, China, Vietnam, and Cambodia, all to varying degrees point to the catastrophic consequences of attempting to leapfrog capitalism and go straight to post-capitalism. All collectivized peasant agriculture while attempting to force industrialization via state fiat, to disastrous effect for many who endured it and, not incidentally, the environment as well.

By contrast, and against claims that capitalism in wealthy industrialized countries has avoided immiserating the Western working classes only by robbing the global periphery of wealth and resources, the spread of global trade, markets, and productive forces to the periphery has coincided with dramatic improvements of living standards and human material well being, from life expectancy to educational attainment to food security, most especially among the global poor.

That period corresponds not incidentally with the collapse of the Soviet Union and China’s embrace of state capitalism and global trade. The global economy remains deeply inequitable. But the floor for virtually all has improved significantly, suggesting perhaps, to paraphrase Joan Robinson, that the only thing worse than being exploited by capitalism is not being exploited by capitalism.

In the advanced developed economies, meanwhile, increasingly social forms of capitalism, as James O’Connor would have it, have not only assured that workers would benefit from a greater share of capitalist surplus but increasingly shifted control over the means of production to workers. Even in the famously unequal United States, workers own a substantial share of the stock market, primarily through retirement plans as well as taxable investment accounts. 66% of US households own their homes. Redistributive tax and transfer programs have actually substantially reduced the income gap between those at the bottom and those at the median of the income distribution, even as incomes at the top have taken off. And even income growth at the top of the distribution has largely been driven by wages, not rents, among top earners in the service and knowledge professions.

Government spending, meanwhile, now accounts for over 40% of GDP in the United States, higher in most other advanced developed economies. Third sector spending—universities, social agencies, and other non-profits—accounts for a further 10%. 25% of Americans work in either the public or non-profit sectors. Another 10% are self-employed. If you want to know why the Left has largely abandoned faith that the industrial proletariat might lead the way to a revolutionary post-capitalist order, consider that about as many Americans today work in the non-profit sector as in manufacturing.

Viewed as a dialectical and emergent phenomenon, not as a radical or revolutionary break, in other words, advanced post-industrial societies have evolved in ways not so different than Marx imagined they would. 150 years of contradictions and crises have transformed capitalism into something profoundly different than what it was in Marx’s day. The mixed economies of the West have proven adept at distributing surplus sufficiently to assure that workers can afford to be consumers of capitalist production. Against the claims of O’Connor and John Bellamy Foster, there is little evidence that a second contradiction of capitalism has much constrained the profitability of capital, despite the presence of an increasingly baroque environmental regulatory state and notwithstanding breathless forecasts of impending disaster fueled economic calamities due to climate change.

Insofar as there are new class conflicts and contradictions in late capitalist societies driving history forward, it would appear to be neither the conflict between capital and labor, nor between materialism and ecology, but rather between the working and knowledge classes—between those with college educations and those without, those still involved in the production of material goods and services and those fully ensconced in the knowledge economy, those in the private sector and those in the public and non-profit sectors that capitalism’s surplus makes possible. These new class conflicts cut across the old distinctions between capital and labor and instead divide both capital and labor, with owners, managers, and workers who produce economic surplus in the private sector increasingly arrayed together against those who live off its rents in the public and non-profit sectors.

Today, this new divide represents a third contradiction of capitalism. Public policies and social forms of production that distribute both private surplus and public goods broadly across late capitalist societies have produced a growing class of rentiers, managers, and workers alienated not only from the means of material production but from the material economy itself. Capitalism produces such wealth and abundance that a growing share of the population becomes detached from the material processes and productive forces that allow for its reproduction.

It is this contradiction and crisis that is today, across the West, roiling the social, political, and economic order that has defined Western political economy since the end of the second World War. The fault lines aren’t neat or tidy. But they define the politics of most Western democracies today. Political alignment today runs along the contours of education, private sector employment, and involvement with sectors of the economy that still produce material goods. If it can be said that there is a rift, it is not between humans and nature but between the new post-material knowledge class and the material metabolism of capitalism itself.

The Third Contradiction of Capitalism

The new divide challenges the old materialist Left as well as the new post-Marxist Left. The organized industrial proletariat has long been a shrinking force in advanced economies, and not simply due to the predations of capitalists. Increasing labor productivity has shrunk employment in industrial sectors of advanced economies. This has not resulted in mass technological unemployment, as both Marx and many of the classical economists he criticized imagined. Material output continues to grow, albeit more slowly than in earlier periods. But labor, freed today from industrial production, as it was in Marx’s time from agricultural production, has been absorbed by massively expanded knowledge and service sectors in all of the advanced economies. 80% or more of both employment and economic output in advanced economies today occurs in those sectors of the economy.

A post-industrial leftism, then, would seem to offer more promising possibilities. In societies where material sufficiency, if not abundance, is assured for virtually all, an egalitarian politics decoupled from material need might, in theory, reorient itself around ecological concerns. But where material interests offered the old Left a mechanism capable of organizing class interests in a way that was both universalizing and disciplining, post-material politics offers no similar mechanism.

Once advanced economies successfully address industrial pollution in extremis—river fires, smothering air pollution, and the like—environmental policies frequently impose costs upon either production or consumption that often hit working class households the hardest, in pursuit of environmental and public health benefits that are, under the best of circumstances, not so stark as to make those benefits obviously worth pursuing. The tradeoffs associated with climate mitigation are even worse. It may be the case that the impacts of climate change will fall hardest upon the poor, but climate policy also often impacts working class constituencies the most, promising higher cost energy, transportation and consumer goods in the present in exchange for uncertain climate benefits decades in the future.

In response, an elite leftism grounded in the academy has weaponized scholarship, scientizing green ideological, cultural, and aesthetic demands as ecological necessities. It is here that the Left, long the enemy of Malthus and subsequent attempts to impose external limits upon the aspirations of the working classes, abandoned that faith, substituting global ecological limits for universalist and class-based material

demands and insisting that the working classes must subordinate their material interests to hard biophysical realities that, definitally, can brook no dissent.

Saito, Foster, and their cohort at The Monthly Review predictably embrace the planetary boundary thesis—arguing that looming ecological collapse requires an eco-socialist future without large-scale agriculture, abundant energy, or mass consumption. In a telling recent exchange with Foster, the Marxist scholar David Harvey rejects Foster’s efforts to base his new-fangled ecosocialism upon neo-malthusian and naturalized claims of planetary boundaries, arguing, as leftists from Marx onwards have, that these have always been tools that elites use to deny power, agency, and resources to the working class and the poor. In response, Foster simply restates his claim that ecological limits are established, unimpeachable science while defending long debunked works, such as Paul Erhlich’s Population Bomb and the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth report, that have inspired exactly the regressive and unjust responses from elites that Harvey warns off.

In any event, the effort to convince the working classes that looming planetary environmental crises require that they subordinate their material aspirations to ostensibly unbending ecological limits has not gone well. The college educated Left today insists that the working classes must forego material consumption that ecoleftists deem unnecessary. But necessity and sufficiency are ultimately in the eyes of the beholder. Whether working class and rural French motorists can afford to pay higher fuel taxes or Dutch farmers can survive economically while raising fewer animals or working class Hispanic men need “big ass trucks,” is largely beside the point. Popular sentiment rules and efforts from both the reformist and radical Left to reorient popular politics around ecological concerns have broadly failed almost everywhere, consistently ceding working class constituencies, and the balance of power, to the populist Right.

In the post-war era, assuring that all were able to meet their material needs and live and work in dignity was a political project capable of sustaining a broad majoritarian politics for the Left. Attempting to codify what constitutes “enough” and impose that upon the population, by contrast, offers no similar possibility for a broad, inclusive, or class-based politics. Once material necessities have been met for most or all in advanced developed economies, politics becomes, unavoidably, a competition of which political faction can best align its objectives and agenda with the values and aspirations of the working and middle classes, including their aspirations to consume more.

Whether under the guise of carrying capacity, planetary boundaries, limits to growth, or climate targets—the effort to constrain the material aspirations of the working classes is a recipe for driving them out of the center-left political coalition. The defilement of Marx by the ecosocialists, in this way, is exactly analogous to the capture of the Democratic Party and center left politics by the environmental movement more broadly. The working class has no interest in being told how much is enough. Whether under the banner of abundance, liberalism, or leftism, the center-left will have no future so long as environmentalists retain substantial power within that coalition.