By Ted Nordhaus

A year ago, I took a public stand in opposition to the confirmation of Matthew Marzano to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. To his advocates, Marzano brought unique qualifications to the position. He was a trained nuclear engineer who had worked as a reactor operator. For me and other opponents, he was a young Senate staffer with a few years of training and experience in the industry and very little policy-making or management experience. He had also led opposition to a key provision of the ADVANCE Act directing the NRC to modernize its mission to enable the benefits of nuclear energy to society, a key litmus test for genuine efforts to reform the agency.

Marzano was ultimately confirmed on a straight party-line vote in the dying days of the lame duck Congress last December, the first commissioner ever confirmed without a single vote from the opposition party in the history of the commission. Since then, the polarization of Congressional politics around commission appointments and business has only gotten worse.

In January, the chair under President Biden, Christopher Hanson, refused to resign from the commission, as his predecessor Kathleen Svinicki had, to allow the newly elected President, who has made nuclear energy a key part of his energy dominance agenda, a working majority on the commission. Instead, Hanson stayed on the commission, positioning himself in a speech in March at the NRC’s annual Regulatory Insights Conference as a fierce defender of NRC independence. Hanson’s obstinance became a self-fulfilling prophecy in May when President Trump asserted his authority over the commission and removed him. Then, in July, the current chair, David Wright—despite being a popular sitting commissioner with a demonstrated track record of both independence and working well with commissioners of both parties—was opposed by the entire Democratic Senate Caucus, in protest of Trump’s removal of Hanson.

The descent of commission politics into the same polarization that has consumed the rest of our body politic is, perhaps, not surprising. But it is not great news for nuclear energy, which in recent years has defied the odds and managed to stay, mostly, above the partisan fray.

So in service of defending the bipartisan consensus in support of nuclear energy and an NRC commission that operates based on evidence, merit, and the national interest and not ideological or partisan commitments, I want to say for the record that Matt Marzano has proven to be a much better commissioner than I feared. It is early days. But he clearly cares deeply about the technology and its future. He has acknowledged that he was wrong to oppose the mission modernization mandate in the ADVANCE Act, making a strong case for mission modernization in his vote for a revised mission statement that went well beyond the very limited revision proposed by the agency’s office of general counsel. He brings useful knowledge of nuclear technology to the commission.

To his credit, he reached out to me within hours of being confirmed to say that he wouldn’t hold a grudge and his door was open to my colleagues and I, a commitment that he has kept. I note that not just because I appreciate the gesture personally but because it speaks to personal character that cannot be quantified on a CV. It also stands in stark contrast to several of his current and former Democratic colleagues on the commission, for whom any criticism of the agency, much less personal criticism, was too often viewed as an assault upon the agency’s independence and integrity.

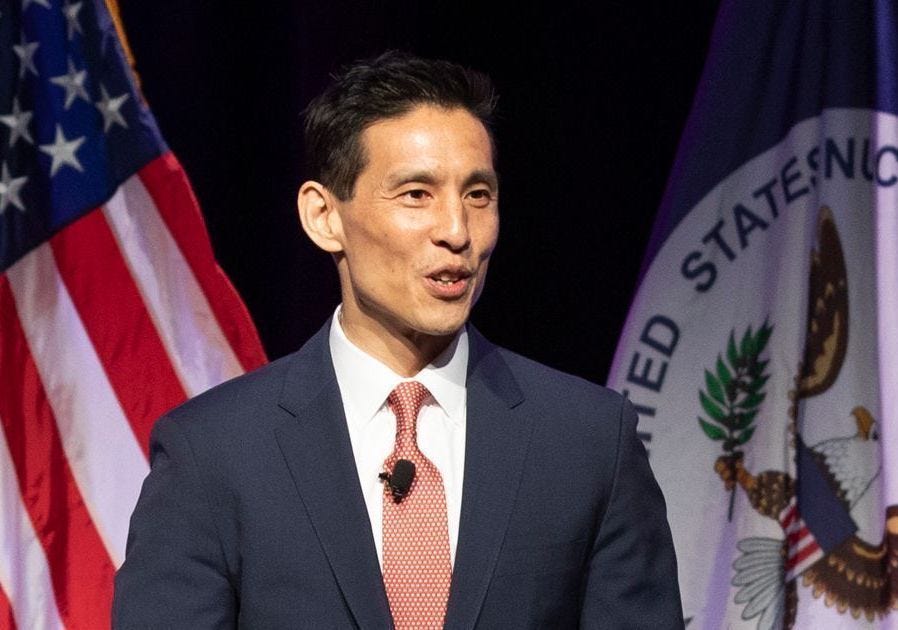

I note all of that also because President Trump has now nominated another commissioner, and against a lot of fear that he planned to stack the commission with flunkies, ideologues, and bomb-throwers, he has nominated a remarkably qualified and experienced candidate. If you liked the idea of having Marzano, a nuclear engineer and graduate of the nuclear navy with a background in science and engineering, not politics, on the commission, you should love the idea of confirming Ho Nieh.

Nieh too is a nuclear engineer and veteran of the nuclear navy. He served two decades in a variety of leadership roles at the NRC, including Director of the Office of Nuclear Reactor Regulation (NRR) and Chief of Staff to Commissioner William Ostendorff. He was well known within the building as a reformer and innovator. And his advocacy within the NRC for regulatory modernization ran well ahead of the changes that have slowly begun to take hold at the agency in the last few years.

After Congress passed the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act (NEIMA) in 2019, directing the NRC to prioritize modernized, risk-informed regulation, and five years before Congress would take the further step of directing the NRC to modernize its mission to enable the safe use of nuclear energy, Nieh unilaterally revised the mission of the NRR, sending a memo to all staff in the division announcing that henceforth the division’s purpose would be to “make safe use of nuclear technology possible.”

This is the sort of statement that to an outsider seems nothing short of banal. Of course the objective of a nuclear regulator should be to enable the safe utilization of clean, reliable energy in the public interest! But in the insular world of the NRC bureaucracy, these words were earth-shaking and controversial, despite clear Congressional direction to modernize the agency and accelerate licensing of advanced reactor technology.

The whole memo is worth reading. It largely anticipates the multiple debates about what real reform at the agency would need to look like in order to serve the nation’s interest as efforts to commercialize a new generation of reactor technology ramped up and often foundered upon the shoals of the NRC’s sclerotic regulatory norms and practices. Nieh’s effort, unsurprisingly, sparked backlash at both the staff and commission level. I can’t confirm it but it has long been rumored that he was forced out in 2021 by a cabal of commissioners who felt that he was pushing too hard for change at the NRR.

Since he left the NRC, Nieh has played an important role in getting new nuclear technology deployed in the private sector, working for Southern Company to oversee regulatory compliance as the company brought the first new US reactors in decades on line.

So the nomination of Nieh will be a test for Congress, and especially Senate Democrats. If competence, independent judgement, technical merit, a deep knowledge of how America’s nuclear regulatory bureaucracy presently operates, and of how it needs to change, matters at all, the Senate will confirm Nieh by a large, bipartisan majority. If Senate Democrats are determined to embody the resistance to all things Trump, even when the vote in question is for exactly the thing that Democrats have demanded—independent, highly qualified leadership at the NRC committed to the safe operation and development of nuclear power—then it will likely come down to a party line vote.

Here’s hoping that wisdom, bipartisanship, and better angels prevail and Democrats are able to put aside their not unjustified concerns about the Trump presidency to confirm a candidate whose qualifications, temperament, and track record as a regulator, corporate leader, and innovator are impeccable. Now more than ever, America needs a next generation nuclear industry, capable of meeting the nation’s growing need for clean, firm, and reliable generation to power rapidly growing electricity demand and compete for global markets.

After a generation of conflict over the role of nuclear energy in the nation’s future energy system, both parties largely agree that it must be a top priority. Achieving that future will require leadership at the NRC that is both highly competent and visionary. The nation couldn’t ask for a better leader on both fronts than Ho Nieh. At a moment of rising polarization and conflict across the political spectrum, here is one small corner of the federal enterprise where Congress can strike a blow for unity and comity in the national interest.