How Much Progress Has California Made to Reduce Wildfire Risk Since the LA fires?

Not Enough

It has been just over a year since the Palisades and Eaton wildfires took the lives of 31 people, destroyed on the order of 15–20 thousand homes, and caused tens of billions of dollars in property damage. Since then, the State of California has made only small progress in reducing the potential for future catastrophic wildfires, with more meaningful mitigation hamstrung by bureaucratic kludge, weak leadership, and pushback from narrow interest groups.

Forest fires are a natural part of California’s ecology, and megafires are an inevitability of decades of lackluster fuels management, population and infrastructure growth, and urban planning. But the scale of damage caused by the Palisades and Eaton fires is not an inevitability. The set of solutions for preventing catastrophic wildfire is well-understood: risk-targeted fuel management; home hardening and defensible space maintenance; and avoiding home construction in high-risk areas. In the years leading up to the LA fires, California failed to adequately follow through on all of these. In the year since, it has made tentative progress, but it is still far from what is needed.

Wildfire risk, like natural disaster risk more broadly, can be understood through a simple formula:

risk = hazard x exposure x vulnerability

Hazard is the potential harm posed by a physical event; exposure is the extent of people and property in harm’s way; and vulnerability is the ability of people and property to withstand that harm. To meaningfully reduce wildfire risk and avoid future catastrophes, California must make much more progress across all three categories. But, if the last year is any sign, don’t hold your breath.

Hazard

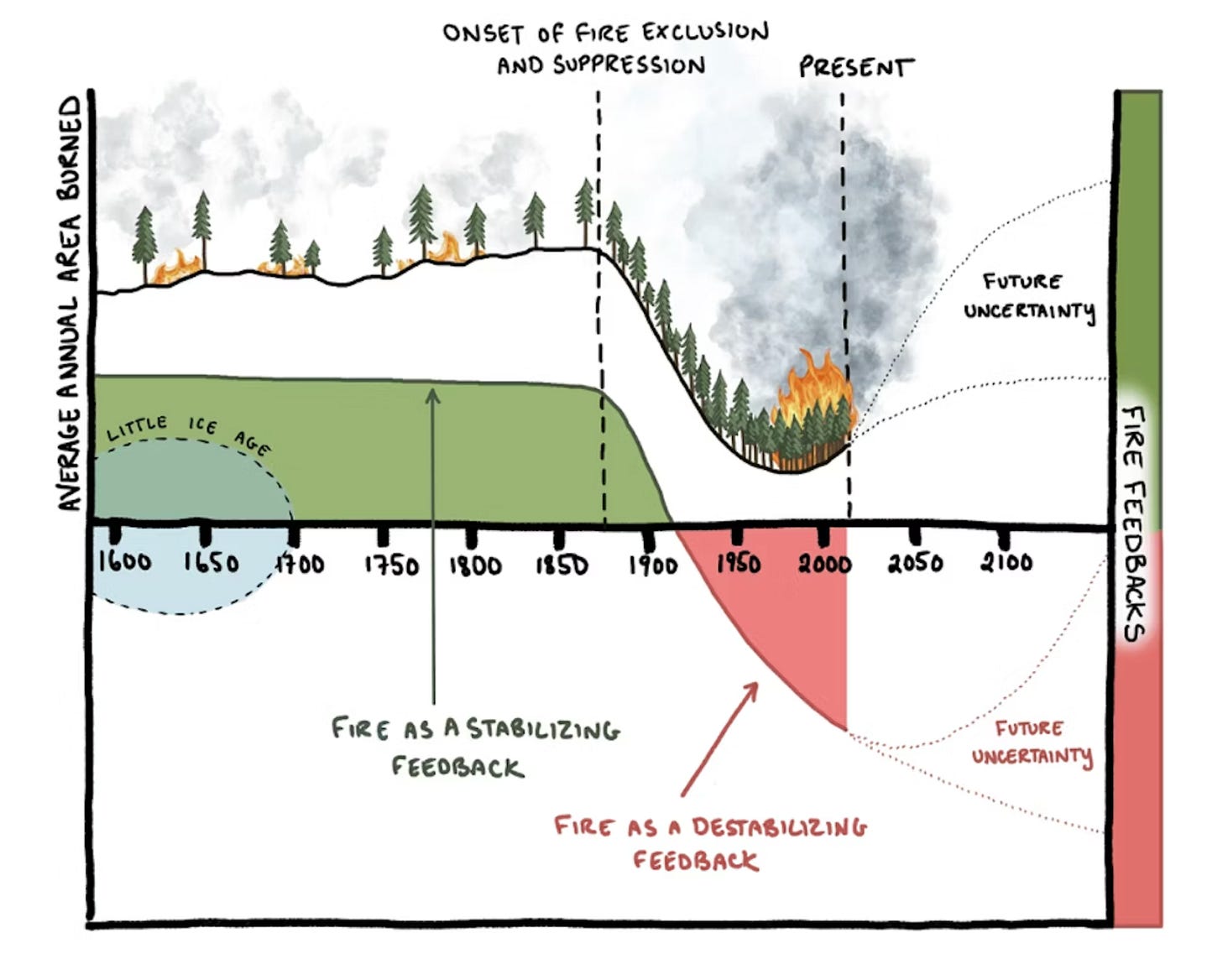

As Patrick Brown explained last year in an essay on The Ecomodernist, fire danger is the product of meteorological and fuel conditions. Fire danger is especially high in 21st century California because of the state’s warm, dry and windy climate combined with a century of fire exclusion policies that allowed the dangerous build up of fuels throughout the state.

Climate change has increased wildfire hazard further in California because, all else equal, warmer temperatures will make vegetation drier, which is then more likely to serve as fuel for fire. World Weather Attribution estimates that climate change increased the intensity of the fire weather conditions observed on the day of the LA fires by 6%, and the likelihood of such conditions by 35%. The effect of climate change in the case of the LA fires, though, is not completely straightforward, because climate change may have dampened the Santa Ana winds that allowed the fires to spread so catastrophically.

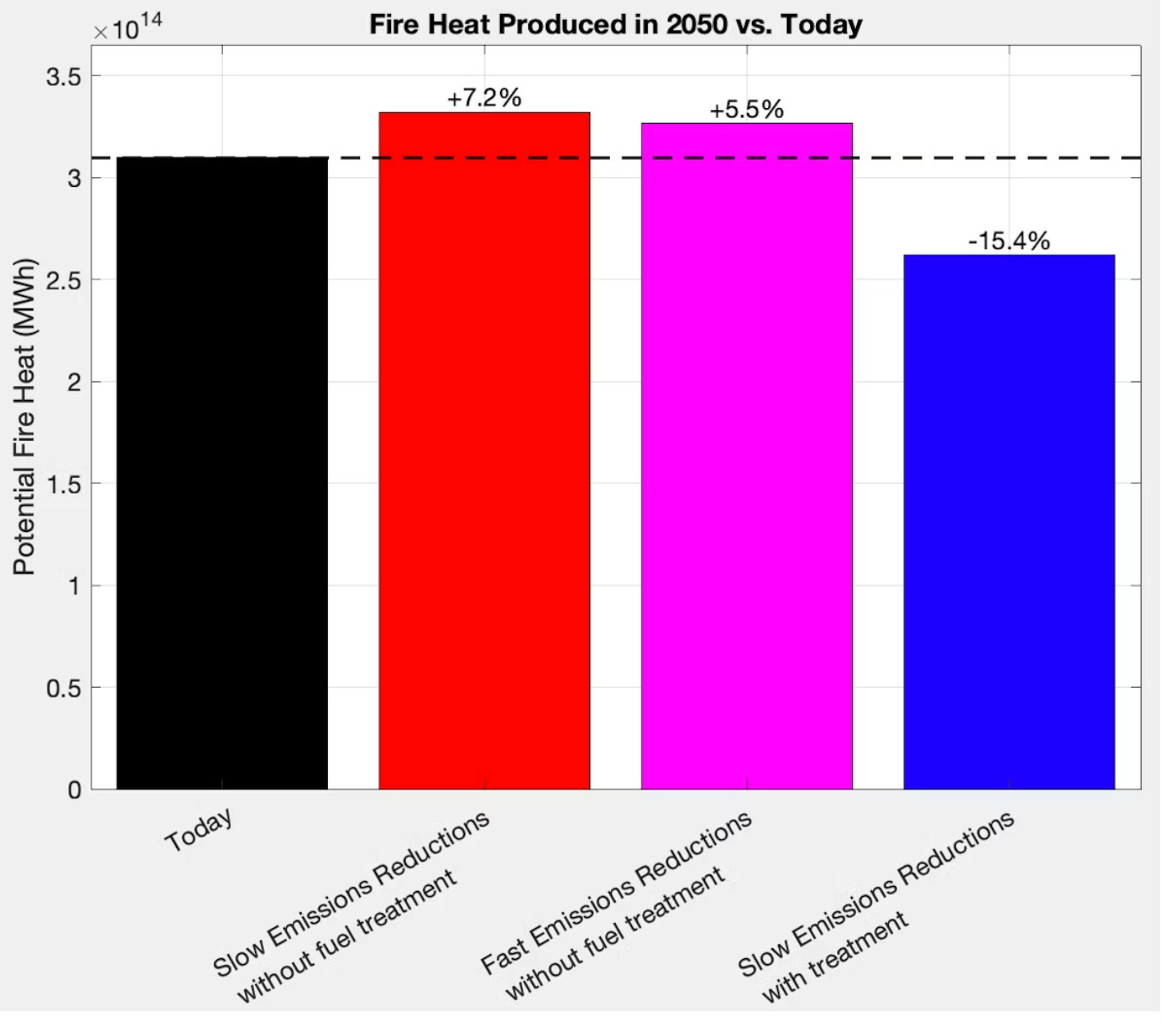

Accounting for less than 1% of world CO2 emissions, there is not much California can do on its own to stop climate change. It is, however, well within the state’s power to produce safer fuel conditions—that is, manage vegetation in a way that is less likely to ignite and spread fire. Proactive fuel management in California can more than counteract the fire risk-elevating effects of climate change. According to research from Patrick Brown, even under a slow emissions reduction scenario and increased global temperatures, vegetation reduction would reduce fire intensity in 2050 by about 15% relative to today.

Patrick’s modeling calls for 1.6 million acres of hazardous fuels reduction a year—a little more than half-again the California and U.S. Forest Service goal of treating a combined 1 million acres a year. According to official data, the combined agencies—to their great credit—achieved that goal in 2023 and 2024, largely through mechanical thinning. A sub-goal of annually applying prescribed fire to 400,000 acres, however, fell very short, with only about 200,000 acres of prescribed burns in 2023 and 2024. Between smoke permitting under the Clean Air Act and landowner liability fears, prescribed burns face significant headwinds in California: only 50% of those that are planned are completed.

Acreage alone does not determine the effectiveness of wildfire prevention treatments, however. Those treatments must also be well-targeted. And California’s current fuel treatment regime is rather scattershot, with some criticizing it as “random acts of conservation.” SB 326, a bill this fall that would have called on Cal Fire to model fire risks and conduct long-term strategic planning, was vetoed by Governor Newsom on the grounds of cost, even though the projected annual cost of such modeling—20 million dollars—is about 0.005% of Cal Fire’s annual budget of 4.5 billion dollars, and 0.0005% of the estimated damages from the LA fires.

It should also be said that southern California’s chaparral-dominated landscapes pose a particularly difficult challenge that does not respond to the traditional playbook of thinning and prescribed burning. In these areas, which are characterized by dense, woody shrubs rather than trees, prescribed burns and thinning often provide little to no long-term benefit in reducing fire hazard; in fact, research has shown that attempts to thin or repeatedly burn chaparral can actually increase flammability over time by encouraging fast-growing, highly flammable invasive grasses to take hold. In such landscapes, fire mitigation must instead focus on removing flammable invasive plants and maintaining strategic fire breaks.

What unites mitigation efforts in forested northern California and shrubby southern California is the role of frustrating procedural barriers that block needed hazard reduction projects. It seems that the failure to completely extinguish the Lachman fire in Topanga State Park, which re-kindled a week later to devour the Palisades, was at least partially due to firefighter hesitancy to bulldoze in State Parks-designated “avoidance areas” meant for the protection of endangered plants. Only last week, an almost identical issue arose in northern California when the outgoing San Ramon Valley Fire Chief wrote a widely circulated letter to the Governor claiming vegetation removal efforts in a very high risk area of Mt. Diablo State Park were being obstructed by State Parks officials intent on preserving endangered plants and Indian burial sites. The chief claimed also that 75% of the crew’s budget had been eaten up by administrative compliance while only a quarter went to actual mitigation.

Overall, it seems California is headed in the right direction on hazard mitigation, even if it could be headed there much faster. But even if the state were executing flawlessly—modeling fire risk, targeting treatments, coordinating burn windows—you can never eliminate hazard entirely. There will always be natural variability in weather and there will always be human error. That’s why it’s just as important that the state focuses on reducing exposure and vulnerability—something which it seems to have only just started taking seriously.

Exposure

Californians are now significantly more exposed to fire danger than they used to be. Since 1990, the number of homes in the dangerous wildland-urban interface (WUI) has increased by 42%, with about 1 in 3 Californians now living in the WUI.

Up until very recently, state policy facilitated, rather than discouraged, the rampant residential development of the WUI. Part of this was restrictive urban land use policy that pushed people to the urban fringe. But a lot has to do with the state’s dysfunctional home insurance market.

Functioning home insurance markets are a critical natural disaster resilience tool because they send price signals about where it is safe to live and incentivize homeowners to weatherproof their homes. Unfortunately, due to a couple of well-intentioned policies, California has not historically had such a market.

The passage of Proposition 103 in 1988, which subjected insurance rate increases to the approval of an elected Insurance Commissioner, effectively put price controls on home insurance. This not only blunted price signals but spurred insurers, barred from pricing risk correctly, to simply leave the state. State Farm, the state’s largest private insurer, stopped writing new policies in 2023; in 2024 it declined to renew tens of thousands of existing policies, including in the Pacific Palisades, where 70% of policies were nonrenewed—the highest share of any zip code in the state. Homeowners in the uberwealthy Palisades had been paying extraordinarily low premiums, with home value-adjusted yearly costs lower than in 97% of all U.S. postal codes, according to a Reuters analysis.

Homeowners might have been spurred by these non-renewals to either leave or invest heavily in fireproofing if it were not for the fact they were guaranteed insurance under the FAIR plan, the state’s insurer of last resort. The existence of the FAIR plan, while well-intentioned—it was originally conceived as a recourse for racial minorities denied insurance due to redlining—is dangerous because it facilitates and encourages the continued occupation of the WUI. The FAIR plan is also rather unfair: because claims are funded via an assessment on private plans, homeowners in low-risk areas end up subsidizing those in high-risk areas. In the Pacific Palisades, one of the wealthiest zip codes in the country, an estimated 1 in 5 homeowners were on the FAIR plan at the time of the fires.

The good news is that California has begun taking meaningful steps to address the distorted price signals that led so many residents into harm’s way. At the end of 2024, weeks before the LA Fires, Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara finalized the Sustainable Insurance Strategy, a long-awaited regulatory change allowing private insurers to use forward-looking catastrophe models, rather than historical data, to set rates. The SIS also permits insurers to pass along the costs of reinsurance (insurance for insurers) to customers, a practice that is permitted in every other state but was up until very recently prohibited in California. Unfortunately, the efficacy of these reforms in discouraging risky construction will be somewhat blunted as the SIS also requires insurers to expand coverage in high risk areas. Still, the SIS appears to have helped persuade some insurers to stay in the state.

Even the best insurance reform won’t move the needle on exposure overnight. But these steps suggest California may finally be getting serious about addressing one of the most politically difficult pieces of the wildfire risk equation: the continued expansion and subsidization of development in fire-prone areas.

Vulnerability

The state is making at least some headway in reducing both hazard and exposure; but California’s efforts to reduce vulnerability to wildfires leave a lot to be desired.

It is not a mystery what can be done to protect structures from fire damage. Fire experts have long understood that a defensible five-foot vegetation-free barrier around homes (known as Zone Zero) and hardening measures like ember-resistant vents and non-combustible roofs are key to reducing structure damage. Indeed, post-fire investigations in the Pacific Palisades and Altadena by the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety found that homes with four basic home hardening measures—including a Class A roof, noncombustible siding, double-pane windows and enclosed eaves—had a 54% chance of experiencing no damage in the 2025 fires, even amidst severe conflagration and unfavorably close structure spacing. Homes with more than 25% fuel cover in their zone zero, meanwhile, had a 90% likelihood of damage or destruction.

Fireproofing measures like defensible space and home hardening are crucial not only at the homeowner level but at the community level, because when a critical mass of homes are fireproofed, it can have a herd immunity-like effect, making it tough for fires to spread through the neighborhood.

And yet, despite this clear evidence of the efficacy of home hardening and defensible space maintenance, progress has been stalled by politics. Governor Newsom first proposed statewide Zone Zero regulations back in 2020, which were supposed to have been finalized at the end of 2023. Were it not for widespread homeowner opposition in wealthy areas like Brentwood and the Palisades, every home in the Pacific Palisades would theoretically have had these protections at the time the fire hit. Zone zero started gaining traction again following the LA fires only to be once more thwarted by the same wealthy homeowners this fall, who managed to push off the final rulemaking yet again.

One alternative to the politically vexing territory of mandates is market incentives. In 2022, Insurance Commissioner Lara issued a rule requiring insurance companies to offer discounts for fire mitigation, and insurers are starting to comply. As of 2025, discounts for hardened homes in the highest-risk areas top out at around 13% and adoption remains uneven. Still, this is a hopeful development. If mitigation continues to prove effective, and insurers gather more data, we could see the kind of widespread premium adjustments that eventually transformed windproofing efforts in hurricane-prone parts of the Southeast. Alabama, for instance, now has a robust system of insurance incentives for wind-hardened homes—but it took time, disasters, and buy-in from both the public and insurers. Hopefully a new state program offering fire risk mitigation grants to lower income homeowners will speed the process along.

Finally, while much of the focus has been on individual homes, community-level vulnerability matters too. Shared defensible space strategies—such as neighborhood-scale fuel breaks or coordinated vegetation removal—is just as important when it comes to reducing risk in the wildland-urban interface than household-by-household efforts.

The rebuilding of the town of Paradise, which was levelled in the 2018 Camp Fire that took the lives of 85 people and destroyed 17,000 structures, may provide a roadmap for high risk areas in the years ahead. Despite extensive grumbling, the town now mandates that all new construction conforms to rigorous wildfire safe design standards and has promulgated an ordinance setting out strict defensible space requirements. Paradise’s parks department has also invested in a Wildland Buffer Project - essentially an enormous fuel break ringing the town. With all of these measures in place, homeowners have not only been able to get private insurance, but seen their premiums go down. The rebuilding of Paradise looks to be a wildfire resilience success story in the making.

The Next Fire

Hopefully it will not take devastation on the scale of Paradise for every high-risk municipality in California to take wildfire resilience as seriously. Unfortunately, it seems that this is what it might take. In a recent report for the New York Times, David Wallace-Wells relates how the state has waived building codes in order to hasten rebuilding in burnt areas, which is now progressing with flammable stick-frame construction; meanwhile, civil opposition to home-hardening and zone zero mandates in the areas most at risk remains ferocious. It is likely that in the long term, insurance market reforms will solve some of these vulnerability problems. But in the short term, aggressive hazard mitigation will be needed. The state must redouble its efforts to risk-target and streamline permitting for fuel reduction projects while reducing bureaucratic kludge that slows down execution. Otherwise, California may have another disaster on its hands.

"Were it not for widespread homeowner opposition in wealthy areas like Brentwood and the Palisades, every home in the Pacific Palisades would theoretically have had these [fireproofing] protections at the time the fire hit." Zen rock gardens might be a win-win-ish strategy - great aesthetics and zero flammability!