Environmental Law After Environmentalism

Why the Next Generation of Environmental Regulatory Policy Needs to Build, Not Restrict

By Ted Nordhaus

I was privileged this week to give the 2025 James L. Huffman Lecture at the Lewis and Clark Law School, which features one the leading environmental law programs in the country. What follows is a lightly edited version of my remarks.

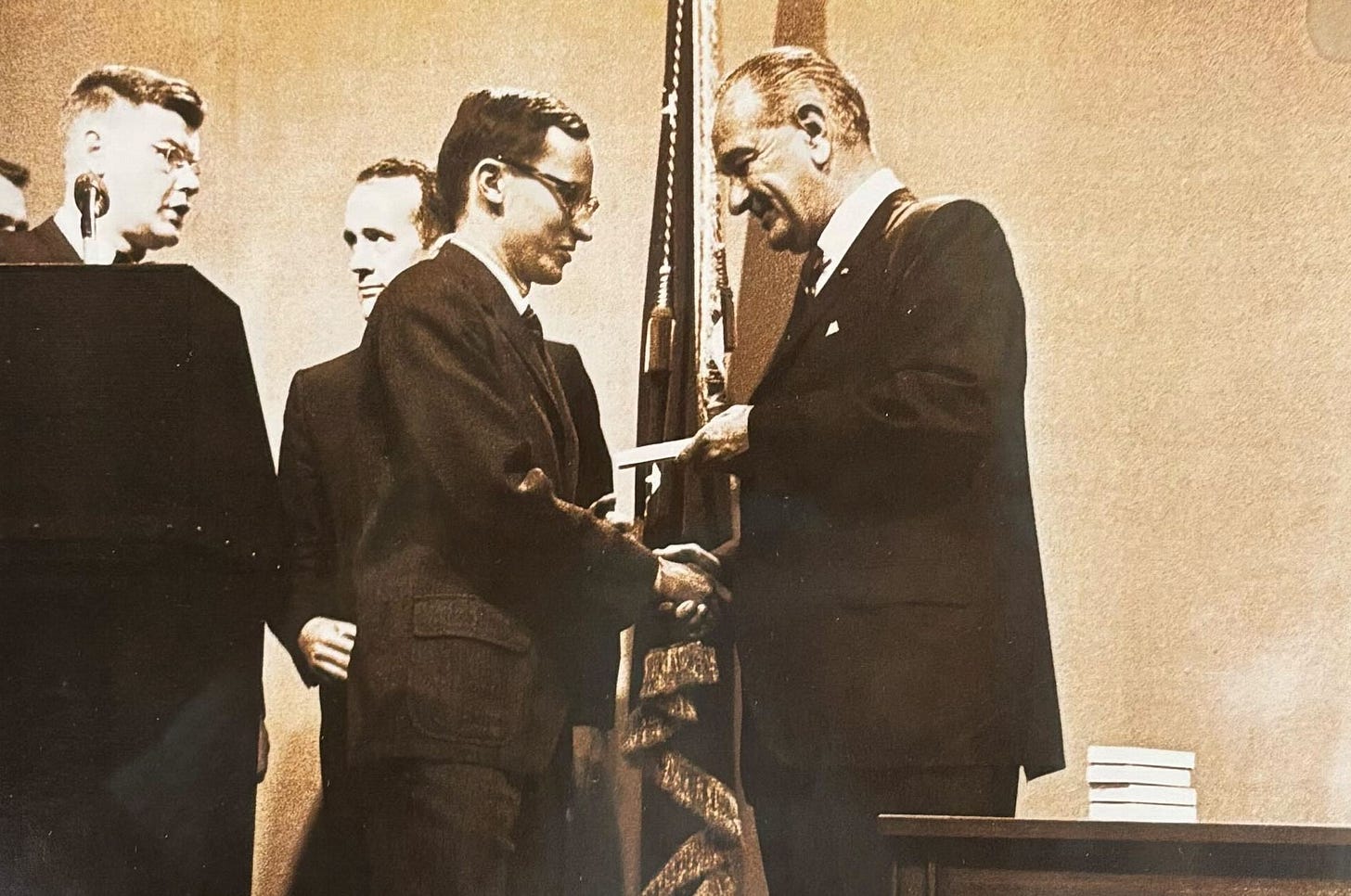

In the summer of 1963, my father, Bob Nordhaus came to Washington, fresh out of Yale Law School and ready to help build Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. He started out doing tax law but quickly shifted gears and increasingly came to specialize in environmental law just as the foundational federal environmental statutes of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s were being enacted. I like to joke that my father was the first environmental lawyer in Washington. He never identified as such. But while I can’t exactly prove the claim and I’m not even sure how one might adjudicate it, he surely was among the first practitioners of what we now call environmental law in the nation’s capitol.

During those years, he had a major hand in drafting almost all of those foundational laws—the Federal Clean Air and Water Acts, the Federal Endangered Species Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act. He is credited with personally drafting Section 111D of the Clean Air Act, the provision under which the EPA has attempted to regulate carbon dioxide as an air pollutant. He also played a major role in drafting most of the post-oil embargo federal energy policy of the 1970s. After passage of the Federal Energy Reorganization Act in 1974, he was delegated to the Federal Energy Administration to help create what would become the Department of Energy and then served during the Carter Administration as the first general counsel to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, where he drafted and implemented the rules that opened up the US electrical grid to merchant power providers and renewable energy.

He was a lifelong Democrat and after a few years in private practice, he went back into government as General Counsel to the Department of Energy in the first Clinton administration, just as the US and the world began to grapple with the problem of climate change. That experience inspired him to build what is generally regarded as the first climate legal practice in Washington after he left government for good.

When he started, in the late 1960s, there was little by way of an environmental movement and nothing in the way of environmental law courses, specialists, or clinics in law schools like this one. And yet, without either a movement, a corpus of legal theory and case law, or an army of practitioners, the United States passed a series of profound and far reaching environmental laws over the course of little more than five years unlike anything that has occurred before or since. And the results were impressive. By the mid-1990s, the nation’s air and waterways had become dramatically cleaner. EPA rules had largely phased out leaded gasoline. And the Endangered Species Act brought iconic species such as the Bald Eagle and the Humpback Whale from the brink of extinction.

By the time that he died, in 2016, the US environmental movement had become a multi-billion dollar enterprise. Walk around Washington today and you will find entire buildings owned by major environmental NGOs and stocked with armies of lawyers, scientists, advocates, and political operatives. And yet, one would be hard pressed to think of a single federal law passed by the US Congress over the last 30 years that remotely rivals any of the foundational laws passed in the early days of environmental law and policy-making, not since at least the 1990 amendments to the Federal Clean Air Act, which took on, and solved the acid rain issue and significantly expanded federal regulatory efforts to address air toxics.

Since then, the most significant legislative accomplishments of the environmental movement have been passage of subsidy programs for clean technology through Democratic budget reconciliation packages, the most significant of which, the Inflation Reduction Act, was largely repealed just a few years later when political control of Congress and the White House flipped. Congressional efforts to tax and regulate greenhouse gas emissions, meanwhile, have failed so spectacularly that neither the Biden administration nor Congressional Democrats, despite proclaiming climate change to be an existential threat befitting a “whole of government” campaign to eliminate emissions, even attempted to legislate emissions limits or taxes while they controlled both the executive and legislative branches.

Instead, most of the action has shifted to the executive branch and the courts. Democratic presidents have used their powers to designate national monuments and taken other actions to protect public lands from various forms of development and use. And we’ve witnessed incremental expansions of federal environmental regulatory powers, achieved either via executive fiat by Democratic administrations or through evolving case law and legal precedent via the courts. Whatever progress these latter efforts have achieved, it would seem that the pace of progress toward improving the environment over the last fifty plus years has been inversely proportional to the scale, sophistication, and resources of the environmental movement and the environmental law community.

So what I want to talk about today is three things. First, why, despite so many more resources being dedicated to the problem, progress has slowed. Second, what exactly is it that all these environmental lawyers, upwards of 30,000 nationally according to Grok, have been up to. And third, whether the modes of legal and policy combat that have become so ingrained within the environmental movement are hindering, or helping, the cause and what needs to come next.

Polarization, Resistance, and Diminishing Returns

Let’s begin with the why first. Why, after such stunning success in the first decade or so after the late 1960s flowering of the environmental movement, has progress been so much more halting?

Well one reason, the one that the environmental community tends to emphasize almost exclusively, is that the business community mobilized to resist further strengthening of environmental laws. And this is surely true. Early environmental advocacy swept through Congress much the way that European diseases swept through the pre-Columbian populations of the Americas. There was no resistance.

Almost all of the modern methods that corporations today use to influence government and policy-making—political action committees, sustained and professionalized lobbying operations, public advocacy campaigns, fly-ins and other efforts to bring local leaders and citizens to Washington to lobby their representatives—were invented originally by the public interest movements of the 1960s and 70s. But it didn’t take long for corporate America to catch on and, as a result, the blitzkrieg that characterized the first decade of federal environmental policy-making morphed into the trench warfare that has characterized the last four decades.

A second reason progress has slowed has been the increasing polarization of American politics. You can go back and read Richard Nixon’s statements about the environment in the early 1970s and he often sounds like a degrowther. Nixon didn’t, by most accounts, mean very much of it. But the fact that he felt the need to speak about the environment in this way points to just how different the political environment was.

America’s great environmental accomplishments were achieved just as the post-war liberal consensus was drawing to a close. Thanks to the New Deal, the war effort, and the extraordinary success of America’s mixed post-war economy, Americans had far greater faith in government. The Cold War and the presence of an ideological competitor to the American-led liberal international order imposed strong incentives on both parties to cooperate to some degree on issues like civil rights, poverty, and the environment, the better to demonstrate America’s superiority to Soviet communism.

The two political parties were also less coherent ideologically and more organized around parochial concerns. It is not coincidental that the last great federal environmental legislative achievement, the 1990 Clean Air Act, came just as the Cold War was drawing to a close and was largely a regional battle, uniting Democrats and Republicans representing the Northeast, which bore the brunt of the acid rain problem against Democrats and Republicans from the industrial midwest, where the pollutants responsible for the problem were being emitted.

But a third reason has been just how successful those early environmental efforts were. Even before the wave of environmental laws in the early 1970s, many pollution problems had vastly improved. Consider that the 1969 Cuyahoga River fire, which famously sparked much of that era’s activism and policy advocacy, was the last significant river fire in American history, and it was hardly significant. It burned for about 15 minutes and had been extinguished before anyone was able to take a picture of it. As Case Western Law School’s Jonathan Adler has documented, industrial river fires occurred regularly throughout the late 19th and early 20th century. The photo of a burning river that Time Magazine splashed across its cover a few weeks later was identified as the Cuyahoga River but was actually that of a far larger river fire in Pittsburgh that had burned for several days more than a decade earlier.

Smog produced from automobiles, by contrast, was a relatively more recent problem, as car culture took hold amidst the post-war economic boom. But air quality too, mostly due to both industrial activities and the widespread use of coal and wood to heat homes, had been far worse in most American cities in the decades prior to America’s great environmental awakening.

To be clear, even though the public health and visual impacts of environmental pollution may not have been as bad in 1968 as they were in 1948 or 1928 or 1888, they were still quite significant. For this reason, major new federal efforts to reduce those impacts brought big results in short order. Scrubbers and catalytic converters were fairly straightforward end of pipe technological fixes that imposed modest costs. Eliminating major applications of a handful of industrial pollutants with clear environmental consequences—such as DDT, leaded gasoline, and mercury—brought huge benefits.

But as those improvements were realized, further environmental regulatory efforts have brought diminishing returns at increasing cost. After the year 2000 or so, the benefits of new environmental law and policy were increasingly tenuous. New environmental laws and regulations brought largely theoretical benefits. But while you could justify them in theory based upon extrapolating pollution impacts from dose-response models, the actual consequences were difficult to observe in the noisy real world, where they are confounded by all sorts of other social, demographic, genetic, and behavioral factors that often have far greater consequences for public health.

One major Canadian study, for instance, estimated that 90% of environmental cancer burden was attributable to just three sources—solar radiation, naturally occurring radon gas, and particulate air pollution. Only the last of these represents the sort of according to hoyle environmental pollution that the environmental movement has spent the last 50 years attempting to regulate, and even that pollution results from many natural and human activities, from wood burning fireplaces to wildfires to agricultural tillage that the environmental movement has not much concerned itself with.

So in summary, the costs of achieving these increasingly modest environmental gains were greater and there was a well organized and resourced opposition dedicated to emphasizing them to the public and policy-makers. And the political climate was increasingly hostile. Merging the environmental movement with the Democratic Party sparked an equal and opposite reaction within the Republican Party and the public was increasingly skeptical of both the overheated claims of environmentalists and the efficacy of government to effectively address environmental problems at acceptable costs.

The Deep Environmental Regulatory State

The response to these challenges, from the environmental movement broadly and the environmental law community more specifically, however, was not to recalibrate. Rather, it was to burrow in and attempt to repurpose the foundational legal frameworks of the early 1970s towards purposes for which they were never intended.

So now, over the last decade, we’ve seen the Obama and Biden Administration attempt to use the federal Clean Air Act to regulate carbon emissions from power plants and tailpipes in lieu of legislating a durable approach to climate mitigation. Environmental groups and Democratic administrations use the Clean Water Acts’ “Waters of the United States” provision, which was explicitly intended to protect navigable waterways, to regulate and limit development around ephemeral streams and seasonal wetlands. The Endangered Species Act, inspired by the plight of charismatic megafauna like the bald eagle, the blue whale, and the grey wolf is now invoked to protect subspecies, and even varieties, of plants that often can’t be differentiated without a genetic test. And the National Environmental Policy Act, intended to inform federal agency decisions and increase public participation has become, as my colleague and Lewis and Clark alum Elizabeth McCarthy put it, a “litigation hydra” and all-purpose tool through which well heeled private interests, often in the name of the public interest, are able to endlessly relitigate public policies and projects that have been approved by policy-makers who are actually accountable to the public.

The result has been a form of “politics by other means” through which the environmental movement has substituted legal and regulatory legerdemain for the difficult work of building durable, cross partisan political coalitions. Under the best of cases, this strategy has resulted in pitched federal regulatory battles that have seesawed from one administration to another over policies that won’t have much real world impact. Consider the now decade-long effort to use the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon emissions. The Obama administration proposed the Clean Power Plan, designating the combined cycle natural gas plant as the best available mitigation technology and attempting to transform a command and control regulatory framework into a trading program for which there was no statutory authorization. The Trump administration abandoned the Clean Power Plan and proposed instead a minimal heat rate requirement for coal plants. The Biden Administration then proposed to designate entirely unproven carbon capture technologies as the best available technology in a transparent attempt to assure that fossil generation would become so costly that utilities would have to make a wholesale switch to clean energy.

Ironically, there is not much evidence that had the Clean Power Plan gone into effect, emissions would be much lower today. The coal to gas transition, which the Obama administration attempted to impose by fiat, was proceeding just fine before the Clean Power Plan was proposed and has continued apace after it was abandoned. If solar, wind, batteries, and electric vehicles are all that the environmental movement claims them to be, the same fate will befall the now abandoned Biden era power plant and tailpipe rules.

But just as often, the outcomes of this approach to the environmental movement’s declining social capital have been worse than that, as the slow accretion of regulatory rules, legal precedents, and procedural practices over decades has created real environmental harm. Consider three major efforts to scale up lithium production in Nevada. One was blocked over entirely speculative concerns that exploratory boreholes would impact the water table and threaten a species of endangered poolfish that lives in a sinkhole nearby. One was blocked due to a subspecies of wild buckwheat only identified by plant biologists a few decades ago. And one was blocked over claims that it threatened the habitat of the sage grouse, an endangered species with a range of over 11 million acres across the mountain west. These dubious environmental impacts have been holding up efforts to develop a domestic supply chain for lithium, the key critical mineral input that is needed to manufacture all the batteries that are supposed to save the pool fish and wild buckwheat and sage grouse from climate change.

Or consider the fate of the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, which its owner, Pacific Gas and Electric, proposed to shutter due to state environmental rules that would have required it to build a multibillion dollar cooling tower to avoid fish larvae entrainment from the sea water intakes that have cooled the plant for the last 40 years. There has been no evidence of any decline in local fish populations over that period. The state’s environmental regulators had simply made a dubious estimate of how much larvae would be entrained, based on a census of the density of larvae in surrounding waters, and then extrapolated that into an even more dubious estimate of the impact that the intakes were having on local fisheries, despite a complete lack of evidence that the plant had had any impact whatsoever on actual fishery populations. This, then, became the ostensible regulatory justification for imposing billions of dollars of new environmental regulatory costs upon the largest source of clean electricity in the state of California, leading to its planned closure. Only after it became clear that the state would have a difficult time either keeping the lights on or hitting its climate targets did the state’s Democratic leaders reverse course on this absurd journey down the environmental regulatory rabbit hole, a decision that the state’s powerful environmental community continues to monolithically oppose.

So this, it would appear, is in significant part what those 30,000 environmental lawyers have been up to for the last generation. Either promulgating rules like these, litigating them, or helping governments, businesses, and property owners comply with them. And as I look out at this remarkable room of ambitious and talented legal minds, I have to ask whether this has been a particularly good use of those talents and the enormous resources that institutions such as this one have invested in training them?

What Will You Build?

My answer to that last question, obviously, is no. But I would be remiss in offering this sort of provocation without suggesting what I think you all ought to be doing with those talents instead. So let me close with some thoughts about what really does matter for the environment and where it is that the environmental movement and environmental law needs to go from here.

First, the single most important thing to understand, in my view, about ecological politics and policy in the 21st century is that the big challenges are generative, not restrictive. Problems like climate change and biodiversity loss are global and solving them requires building a new world, not preserving the old one. Similarly, the new ecological problems won’t be solved in the old ways that worked so well for the environmental movement in the 60s and 70s. Climate change is not simply a big air pollution problem that we can regulate or tax out of existence. And biodiversity loss won’t be solved by drawing a circle around the Amazon or the Siberian Taiga in the way that earlier conservation efforts created national parks and other protected areas.

If you want to stop climate change, you need to build an entire new energy economy capable of providing far more energy to meet the needs of 8 billion people globally, most of whom want to live modern lives just like all of us do. This is not optional. China, India, and other emerging economies are not waiting for our permission to develop. And if you want to protect global biodiversity, you need to figure out how to produce food for 8 billion people who want to eat higher on the food chain, which means producing more food on less land so that we don’t convert more of our forests, wetlands, and grasslands into agriculture.

So the question for the environmental law profession over the coming decades, in my view, is not what will you stop but what will you build? This, then, leads to a second key question, which is what parts of the enormous environmental regulatory edifice that we have built up in this country are you ready to get rid of so that we can build that world?

There is a lot of concern in the environmental law community that in the rush to reform environmental laws like NEPA and the Endangered Species Act, we will throw out the baby with the bathwater. And my response to those concerns is that if you want them to be taken seriously, you need to be ready to say what you are willing to get rid of. Which part is the baby and which part is the bathwater. There must be something, some significant part of the environmental legal canon that has been built up over the last 50 years, that is no longer fit for purpose and can be dispensed with.

Of course, it may already be too late for the environmental legal community to choose. The Trump administration and the Supreme Court are already well on their way to eviscerating much of the environmental legal canon, wiping out fifty years of legal precedent, administrative law, and regulatory guidance, and emptying the federal bureaucracy of much of the institutional knowledge and expertise necessary to keep the massive federal environmental regulatory enterprise humming along. This is a huge challenge to the ancien regime. Even if Democrats sweep back into power in 2028, it is not at all clear that it will be possible, much less desirable, to put the legacy green regulatory paradigm back together again.

But it is also an enormous opportunity for a new generation of legal scholars and practitioners. After Trump and his MAGA shock troops clean out environmentalism’s Augean stables, there will be a void to fill. Forward thinking environmental lawyers should be thinking now about how they will build a new federal environmental regulatory regime largely from scratch, one that is fit for purpose, that supports innovation and follows technological change rather than attempting to force it, and that builds instead of restricts.

In closing, I want to remind you all that while politics and policy are important, the big long term drivers of environmental progress are macroeconomic and technological, not political or regulatory. As I noted earlier, before any of those foundational laws had been passed, the air and water in the post-war era was already far cleaner than it had been in earlier decades because an increasingly prosperous society was building all sorts of infrastructure for all sorts of reasons that brought environmental benefits along for the ride. Better technologies were making industry, space heating, and all sorts of other activities more efficient and profitable, as well as being less damaging to the environment.

The same is true today of carbon emissions. The long-term carbon intensity of both the US and global economies has been falling at a consistent rate since long before anyone had ever heard of climate change. That is in part due to public policies, particularly public investments in new energy technologies. But many of those policies were undertaken for reasons having not much to do with climate change.

When I was a young activist and advocate, I found this idea distasteful, even identity threatening. The whole reason I got into environmental politics was to change the world. The notion that things had gotten better, environmentally and otherwise, for reasons having nothing to do with the sacred acts of protest, organizing, advocacy, and litigating seemed to challenge the entire point of what I was doing.

My older self sees all that differently. The flowering of environmental concern, activism, and ultimately lawyering in the early 1970s brought a one time bonanza, accelerating trends that were already underway. There was lots of low hanging pollution fruit to capture at very low cost. But the environmental movement learned the wrong lessons from those early successes, overindexed on legal and regulatory strategies, and built an enormous legal and political infrastructure to prosecute those strategies to increasingly little effect.

My point is not to encourage you to abandon environmental activism, policy, or legal efforts all together. But it is to urge a bit more humility and a lot less technocratic hubris. Environmental law and policy succeeds when it swims with the far more powerful currents of modernization, development, economic growth, and technological innovation. When it positions itself oppositionally to those trends, it fails. Growth, development, and technological change are both the source of and solution to environmental challenges. Environmental law must place itself in service of those processes in order to serve the environment.

Superb. Just fucking superb,

Wisdom, history, energy, economic development, health, global perspective, technology, humility and practical environmentalism are rarely found in the same discussion. Thanks, Ted.