Do Climate Attribution Studies Tell the Full Story?

How a cascade of selection effects bias the collective output of extreme event attribution studies.

By Patrick Brown

Weather and climate extremes—such as high temperatures, floods, droughts, tropical cyclones, extratropical cyclones, and severe thunderstorms—have always threatened both human and natural systems. Given their significant impacts, there is considerable interest in how human-caused climate change influences these extremes. This is the focus of the relatively new discipline of Extreme Event Attribution (EEA).

Over the past couple of decades, there has been an explosion in EEA studies focusing on (or, “triggered by”) some prior notable weather or climate extreme. Non-peer-reviewed reports from World Weather Attribution (e.g., here, here, and here) represent some of the most notable examples of these kinds of analyses, and many similar studies also populate the peer-reviewed literature. The Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society’s “Explaining Extreme Events From a Climate Perspective” annual series compiles such studies, as does the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, and they are also synthesized in reports like those from the IPCC (IPCC WG1 AR6 Chapter 11.2.3) and the United States National Climate Assessment.

The collective output of these kinds of studies certainly gives the impression that human-caused climate change is drastically changing the frequency and intensity of all kinds of weather extremes. Indeed, Carbon Brief recently published an extensive summary of the science of EEA studies, which begins with the proclamation, “As global temperatures rise, extreme weather events are becoming more intense and more frequent all around the world.”

This is seemingly supported by hard data from Carbon Brief’s extensive catalog of nearly every published EEA study. Their database includes over 600 EEA studies on about 750 extreme weather events and trends. They report that approximately 75% of these events were intensified or made more probable due to climate change, while only 9% were made less intense or less likely as a result of climate change. This skew towards increased intensity or likelihood is evident across various event types, appearing in ten of their twelve categories.

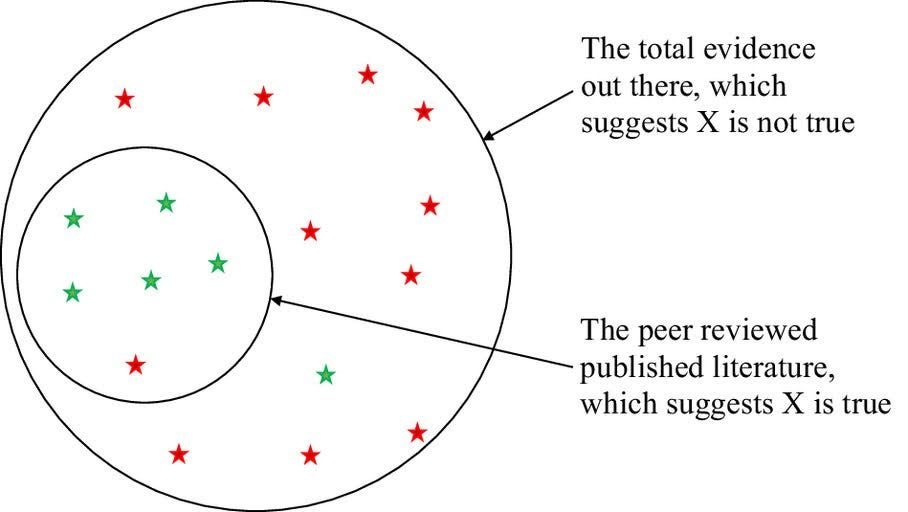

However, these numbers cannot be taken as an accurate quantification of the influence of climate change on extreme weather because they are heavily influenced by a cascade of selection biases originating from the physical climate system, as well as researcher and media incentives. Identifying and understanding these biases is a prerequisite for properly interpreting the collective output of EEA studies and, thus, what implications they hold for general scientific understanding, as well as political and legal questions.

An Apparent Discrepancy?

One might conclude from the collective output of EEA studies that there is strong evidence indicating an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather. Yet, this conclusion seems to be in tension with the more comprehensive evaluations of extreme weather changes found in the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change’s (IPCC) Working Group 1, Chapter 11, and Chapter 12, which are noticeably more reserved in their conclusions on identifying and attributing shifts in these extremes (see also Roger Pielke Jr.’s Weather Attribution Alchemy series).

The IPCC indicates that extreme heat over land is rising at a rate that is roughly equal to, or just below, the mean warming rate for land. This increase, however, is balanced by a decrease in extreme cold. Consequently, there is no substantial global net rise in the occurrence or intensity of extreme temperatures. Furthermore, the IPCC observes that there are currently not detectable globally coherent trends in inland flooding. Drought conditions are variable, with some types of droughts found to be increasing in specific areas, yet there is not evidence of any global trend in meteorological droughts characterized by precipitation deficits. Trends in tropical and extratropical cyclones, as well as severe thunderstorms, all show mixed results with no clear long-term increase.

Overall, the lack of a strong influence of climate change relative to natural variability is exemplified by the IPCC’s Table 12.12, which uses a standardized methodology for the detection of change to assess when (if ever) the climate change signal will emerge from the noise of natural variability for a number of “Climatic Impact Drivers.” The color corresponds to the highest level of confidence reported in any region, and white cells indicate that evidence is lacking or that any climate change influence is not yet detectable above natural variability.

It is notable, especially in the context of the aforementioned Carbon Brief catalog of EEA studies, that there are white cells (climate change not detected) over the historical period for

river flood

heavy precipitation and pluvial flood

aridity

hydrological drought

agricultural and ecological drought

fireweather

mean wind speed

severe wind storm

tropical cyclone

hail

So what is going on?

Cause of the Apparent Discrepancy

The large apparent discrepancy between the size of the influence of human-caused climate change on extreme weather reported in EEA studies (like those compiled by Carbon Brief) compared to more comprehensive systematic analyses (like those compiled by the IPCC) can, in large part, be attributed to the many layers of Selection Biases that influence the EEA literature's collective output.

Selection Bias is a broad term that refers to any bias that arises from a process that selects data for analysis in a way that fails to ensure that data is representative of the broader population that the study wishes to describe.

The type of selection bias that is perhaps most familiar to most people (and a slightly more serious version of the above cartoon) is the Nonresponse Bias of polling, where individuals who do not respond to a poll differ systematically from those who do respond. For example, if Republican voters are less likely than Democratic voters to respond to an election poll, then the poll will have a sampling bias in the sense that the sample (people who responded to the poll) is biased towards Democratic responses and is thus not fully representative of the population that will end up voting in the election.

Selection biases in the context of EEA studies include those associated with the physical climate system itself, those concerning proclivities and incentives facing researchers/journals, and those concerning the proclivities and incentives facing the media. They include Occurance Bias, Choice Biases, Publication Bias, and Media Coverage Bias.

Occurrence Bias is a bias introduced by the physical climate system. Since EEA studies tend to be triggered by extreme events that have actually occurred, there is reason to believe that these studies will disproportionately sample events that are more likely than average to be exacerbated by climate change because the events occurred in the first place. Essentially, extreme events that are more likely to occur under climate change—and thus more likely to be observed—are going to be overrepresented in EEA studies, and extreme events that are less likely to occur under climate change—and thus less likely to be observed—are going to be underrepresented in EEA studies.

The map below illustrates this phenomenon. It shows changes in the magnitude of extreme drought under climate change. Specifically, it shows the fractional change in the intensity of once-per-50-year droughts (as quantified by monthly soil moisture) between a preindustrial and 21st-century run (SSP2-4.5 emissions) of the highly-regarded NCAR CESM2 Climate Model. Blue areas represent locations where the model simulates that extreme droughts become less frequent and intense with enhanced greenhouse gas concentrations, and red areas represent locations where the model simulates that extreme droughts become more frequent and intense with enhanced greenhouse gas concentrations. It is notable that overall, this model simulates that warming decreases the frequency and intensity of extreme drought in more locations than it increases it (consistent with soil moistening under warming simulated by other models).

Now, here’s the kicker: The dots show locations where once-per-50-year droughts actually occurred in the 21st-century simulation and thus represent events that would plausibly trigger EEA studies.

What do you notice about where the dots are compared to where the red is? That’s right; the simulated EEA studies overwhelmingly sample areas where droughts are getting more intense and more frequent by the very nature that those are the types of droughts that are more likely to occur in the warming climate. The result is that the EEA sample is majorly biased: warming decreased the intensity of once-per-50-year droughts by about 1% overall, but it increased their intensity within the EEA sample by 18%! Thus, if you just relied on the EEA sample, you would come away with an incorrect impression not only on the magnitude of change in extreme droughts but also on the sign of the direction of change!

Choice Bias arises when researchers use prior knowledge to choose events for EEA studies that are more likely to have been made more severe by climate change. A clear example of Choice Bias pervading the Carbon Brief database is there have been 3.6 times more studies on extreme heat than there have been on extreme winter weather (205 vs. 57). Another example would be the dearth of EEA studies on extratropical cyclones (the kinds of low-pressure systems with cold and warm fronts that are responsible for most of the dramatic weather outside of the tropics). The IPCC states that the number of extratropical cyclones associated with intense surface wind speeds is expected to decrease strongly in the Northern Hemisphere with warming. Yet, it is relatively rare for EEA attribution studies to be done on these types of systems, which results in an exclusion of this good news from the EEA literature.

Publication Bias could be playing a role, too, where researchers are more likely to submit, and journals are likely to publish studies that report significant effects on salient events compared to studies that find null effects.

Finally, the climate reporting media ecosystem is characterized by actors whose explicit mission is to raise awareness of the negative impacts of climate change, and thus, there will be a natural Media Coverage Bias with a tendency to selectively highlight EEA studies where climate change is found to be a larger driver than EEA studies that do not reach such a conclusion.

These selection biases are apparent at the aggregate level, but there is also strong evidence of their presence in individual studies. My self-critique of my 2023 Nature paper (which was an EEA study on wildfires) invoked my own Choice Biases, Publication Bias, and Media Coverage Bias.

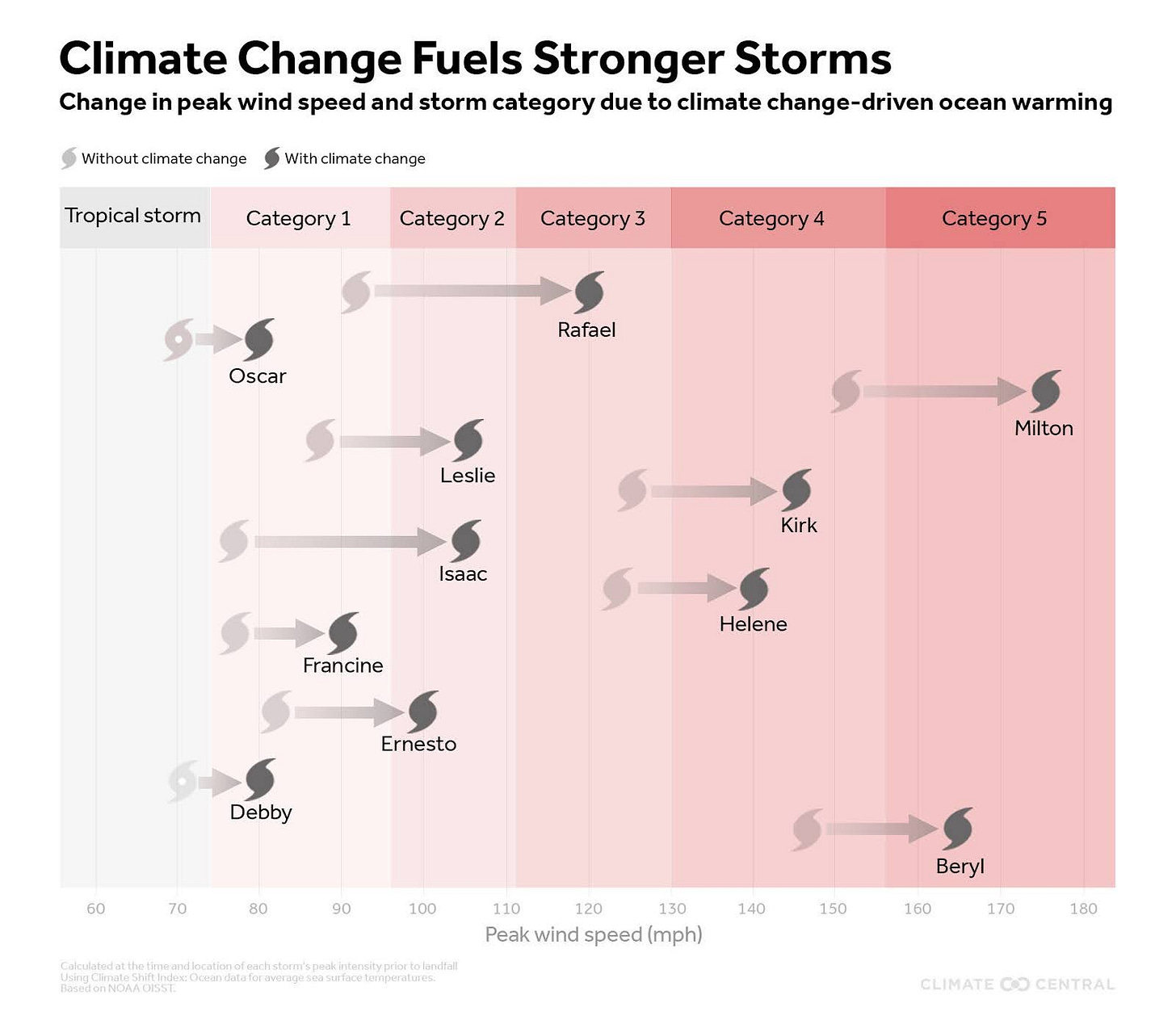

A more recent specific example suggestive of many of these dynamics is a study, Gilford et al. (2024), titled “Human-caused ocean warming has intensified recent hurricanes”. This study was conducted by three researchers at Climate Central, which summarizes the study’s findings with the following infographic:

Essentially, they claim that climate change is enhancing the intensity of all hurricanes and that the enhancement is quite large: Storms today are calculated to be an entire Category stronger than they would have been in a preindustrial climate.

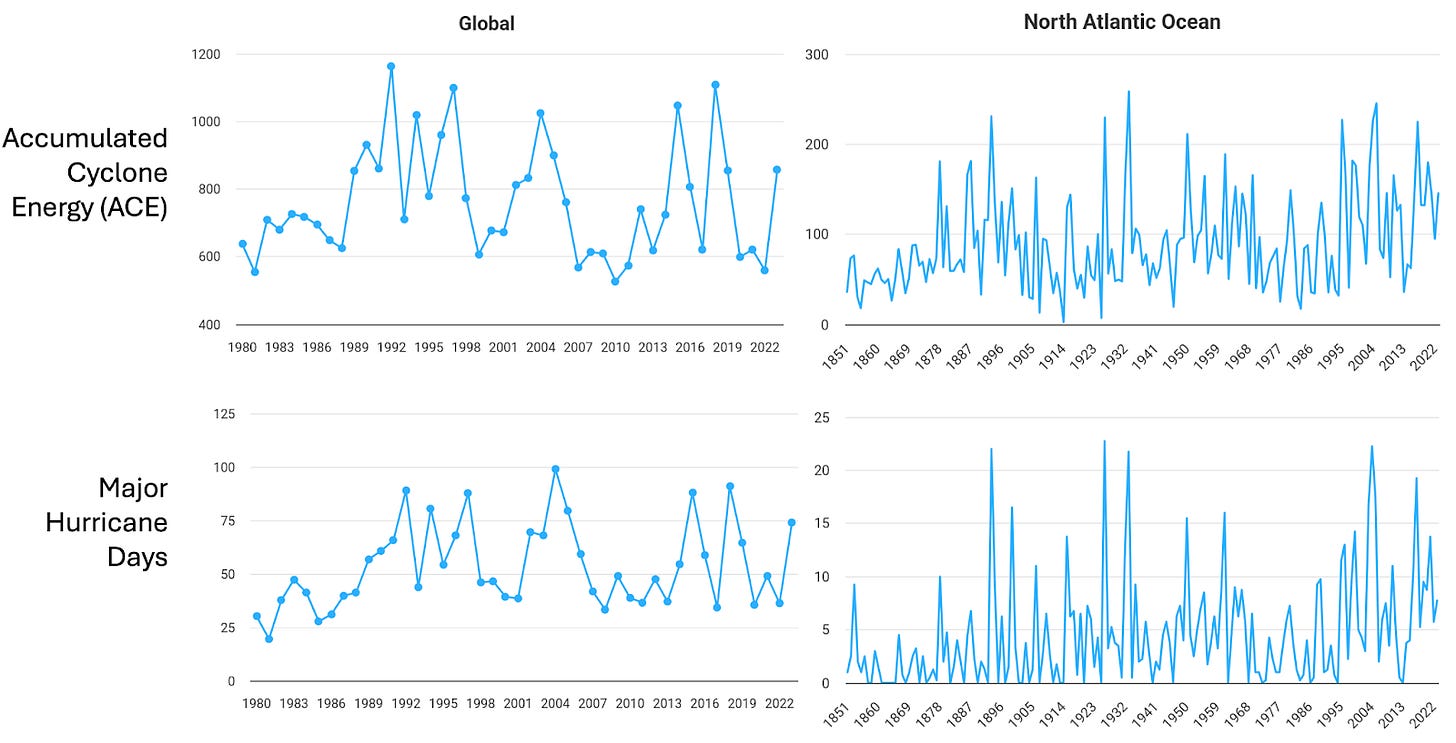

This is a huge effect, and thus, if it were real, it is reasonable to expect to see clear long-term trends in metrics of tropical cyclone (hurricane) intensity like the accumulated number of major (Category 3+) hurricane days or the accumulated cyclone energy from all tropical cyclones (which is proportional to the square of hurricane windspeed accumulated over their lifetimes). However, any long-term trends in such metrics are subtle at best, both globally and over the North Atlantic.

So, this is a microcosm of the aforementioned apparent discrepancy between more broad quantifications of changes in extremes and their associated EEA counterparts, and again, I’d argue there are several selection biases at play affecting the production and dissemination of the EEA study.

Let’s start with Choice Bias on methodology. Human-caused warming changes the environment in some ways that work to enhance hurricanes and in other ways that diminish them. The main way that hurricanes are enhanced is via the increase in sea surface temperatures (which provides the fundamental fuel for hurricanes), and the main way that hurricanes are diminished is via changes in atmospheric wind shear and humidity. The net result of these countervailing factors pulling in opposite directions is that we expect fewer hurricanes overall, but when hurricanes are able to form, they can be stronger than they would otherwise. These factors, though, are small relative to natural random variability, and thus, they are difficult to detect in observations.

However, the Climate Central researchers made the methodological choice to largely exclude the influence of factors that diminish hurricane development from the study. First, it uses a “storyline approach” that takes the occurrence of hurricanes as a given. In other words, although there is good evidence that warming should reduce hurricane numbers, the methodology implicitly holds hurricane numbers fixed. Second, the main reported results are only for the effect of warmed sea surface temperatures on hurricane strength, neglecting the countervailing effects of changes in the atmosphere that would reduce hurricane strength (The study includes a half-hearted and methodologically convoluted attempt to account for the countervailing influences of tropical cyclone strength in one sensitivity that cuts the influence of climate change on wind speeds by more than a third. However this result is not reported in the abstract, main figure, or the study’s infographic).

Climate Central’s headline on their study was “Climate change increased wind speeds for every 2024 Atlantic hurricane,” but this headline would be more accurate if it was immediately followed by “...if we focus exclusively on those aspects of climate which we know intensify hurricanes (sea surface temperatures) and ignore or downplay those aspects of climate change which would work to diminish hurricanes.”

Are these Choice Biases in event type and methodology an accident? There are many reasons to believe they are not.

The research paper itself spells out that the motivation of the study is to “connect the dots” between climate change and hurricanes because “landfalling hurricanes with high intensities—can act as ‘focusing events’ that draw public attention” and that “Increased attention during and in wake of storms creates opportunities for public and private discourse around climate and disaster preparedness.”

It is also relevant that the study was funded by the Bezos Earth Fund, The Schmidt Family Foundation, and the CO2 Foundation, all of which have missions in line with the eventual conclusions of the study (but no potential conflicts of interest were reported by the study's authors). For example, according to the CO2 Foundation’s website, its mission is to “execute impactful grant-making and communication about the urgent societal risks from extreme weather…”

Then, there is the extensive media coverage of this study. It was picked up by 134 news outlets and ranked in the 99.95th percentile of research articles (across all journals) of similar age in terms of online attention. Further, it was immediately incorporated into seven Wikipedia articles (likely having high leverage on AI queries, which would make its findings indistinguishable from scientific “fact”). This is affected by the aforementioned Media Coverage Bias, but it is also undoubtedly directly influenced by the efforts of Climate Central, which is explicitly an advocacy organization whose self-described specialty is media placement and dissemination. In a recent fundraising email, they led with this theme: “The influence our analysis had on media coverage of Hurricanes Helene and Milton before they even made landfall gives just a taste of what we can achieve with your support.”

Motivations behind the skew of EEA studies

The above sheds light on the reasons for certain choice biases in a particular study, but there is plenty of evidence that these selection biases are pervasive in the EEA field. After all, Dr. Myles Allen essentially founded the field with the motivation of answering the question, “Will it ever be possible to sue anyone for damaging the climate?”. This same motivation seems to animate many of the most high-profile scientists in the field today, like Allen’s protege, Dr. Friederike Otto (co-founder and leader of World Weather Attribution). She and her organization are frequently cited as bringing the necessary intellectual authority to credibly sue fossil fuel companies. She states the motivation of her work explicitly: “Attributing extreme weather events to climate change, as I do through my work as a climatologist, means we can hold countries and companies to account for their inaction.”

Similarly, Dr. Emily Theokritoff—a research associate at Grantham, who is working on an initiative to publish rapid impact attribution studies about extreme weather events, similar to World Weather Attribution—told Carbon Brief that “The aim is to recharge the field, start a conversation about climate losses and damages, and help people understand how climate change is making life more dangerous and more expensive.”

Given the explicitly stated motivation of those in the EEA field, it is quite reasonable to suppose that there are major selection biases at play, and thus, it is not at all surprising that the collective output of the EEA field would look so different from more broad comprehensive assessments.

Implications of Selection Biases in EEA Studies

Returning to the apparent discrepancy laid out above, the IPCC Chapters 11 and Chapter 12 are addressing the question:

“What is the impact of human-caused climate change2 on extreme weather1?”

Whereas the collective output of the EEA field appears to be asking the same question, but it implicitly contains two important footnotes:

1 By extreme weather, we mean mostly the kinds of extreme weather that we already know are made worse by human-caused climate change and not the kinds of extreme weather that we know are ameliorated by human-caused climate change.

2 By human-caused climate change, we mean mostly the sub-elements of human-caused climate change that we already know make the kind of extreme weather we are studying worse.

Appreciating these footnotes is critical if we want to communicate our best scientific understanding of the issue to the public and to reliably inform political and legal questions.

The general belief that climate change is greatly impacting extreme weather appears to have grown alongside the surge in EEA studies, reflected in a marked increase in Google searches for “climate change extreme weather."

These EEA studies also carry practical legal and policy implications as they frequently relate to assessed monetary damages from extreme events which means they can be used to bolster support for more stringent greenhouse gas emissions reductions via their inclusion in the calculation of the social cost of carbon. EEA studies are also frequently discussed in the context of the Loss and Damage Mechanism of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change which would mean they could be used to justify climate reparations payments across borders.

Finally, as alluded to above, EEA studies can potentially be used in direct legal actions against entities such as fossil fuel companies. In 2017, two lawyers wrote a Carbon Brief guest post stating, “we expect that attribution science will provide crucial evidence that will help courts determine liability for climate change-related harm.” Four years later, the authors of a study on climate litigation wrote a Carbon Brief guest post explaining how attribution science can be “translated into legal causality.” They wrote: “Attribution can bridge the gap identified by judges between a general understanding that human-induced climate change has many negative impacts and providing concrete evidence of the role of climate change at a specific location for a specific extreme event that already has led or will lead to damages.”

Given the broad scientific and practical implications of EEA studies, it is crucial that the selection biases highlighted here are appreciated and ultimately fought against so that the output of the EEA field can more accurately reflect the overall influence of climate change on extreme weather.