This essay was originally published by the The Boston Globe as “The world’s biggest climate goal was a waste of time and money”.

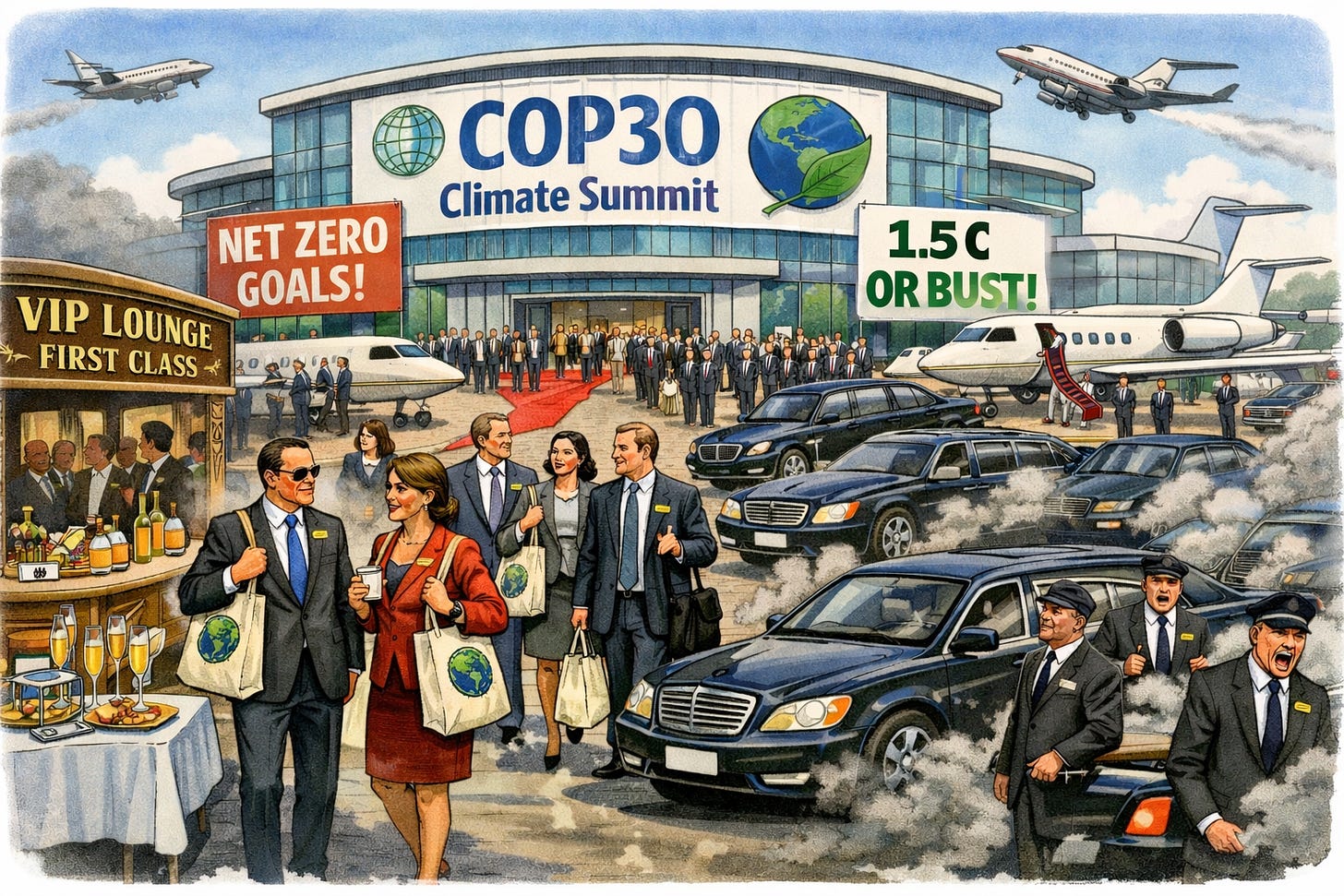

No one is sure exactly how much money the United Nations’ most recent climate confab in Belém, Brazil, cost. The Brazilian government may have spent as much as $1 billion on the November event. Spending by other public and private interests to accommodate almost 60,000 official delegates and countless further corporate and nonprofit participants surely rivaled the government’s expenditures. Whatever the final tally, it almost certainly exceeded the $350 million that rich countries, after years of wrangling, have ponied up in recent years to compensate poor countries for climate losses and damages.

Thirty years after the first Council of Parties, or COP, conference was held in Berlin in 1995, it is not at all clear what the long-running UN-led effort to galvanize international action on climate change has accomplished. Official accounts are contradictory. The UN and other parties insist the world faces dire consequences should atmospheric warming exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. At the same time, many of those voices also claim that international efforts marshaled by the COP have already averted catastrophe, reducing likely warming by the end of this century from 5 degrees Celsius to less than 3 degrees.

The first claim is dubious. There has never been any credible science establishing that 1.5 degrees marks a threshold beyond which catastrophe is assured. The 1.5 degree target was originally put forward in 2009 by small island nations arguing that they would be inundated by rising seas if the world surpassed it. But there is little evidence to date that rising sea levels have particularly threatened the future of island nations. To the contrary, many continue to add coastline and land area through landfilling and other coastal modifications, as low-lying regions have for many centuries. One recent survey found that 221 atolls across the Pacific and Indian Oceans had increased their land mass by 6 percent between 2000 and 2017 despite rising sea levels. So while there is significant uncertainty about how fast sea levels will rise in the coming decades, low-lying areas including small island nations will likely have substantial capability to adapt to those changes.

Nonetheless, in the years after it was adopted at the Paris COP in 2015 as an “aspirational” target, 1.5 degrees has taken on a life of its own. The World Economic Forum claims that “1.5°C is a physical limit beyond which Earth systems enter a danger zone of cascading climate tipping points that propel further warming.” UN Secretary General António Guterres opened the COP plenary in Belém by asserting that “1.5°C limit is a red line for humanity.”

These warnings conflate highly speculative concerns about triggering irreversible geophysical processes with claims that climate calamity has already arrived in the form of present-day disasters. But the data tell a different story. Mortality due to climate-related extremes and disasters of all sorts has fallen dramatically over all relevant timescales. 2025 will likely feature the lowest mortality from climate-related disasters in recorded human history. The economic costs of disasters continue to rise, as the world is both richer and more populous than ever. But those costs have declined significantly as a share of global GDP. Despite the warming climate, human societies are today more resilient to climatic extremes than they have ever been.

The second claim — that international efforts have already averted catastrophe — is risible. The COP negotiations and the Paris Agreement have not significantly altered the trajectory of global emissions. The ostensible progress is an artifact of the misuse of emissions scenarios projecting 5 degrees Celsius or more of future warming, which were never plausible, not a shift in the underlying characteristics of the global energy economy. The carbon intensity of the global economy has been falling at a consistent rate for decades, since at least the energy crises of the 1970s, when nations began collecting decent data. Most advanced developed nations have seen falling emissions for the last two decades or longer, as population and economic growth have slowed and energy technologies have continued to improve. The same processes are now underway across much of the rest of the world.

None of these developments are attributable to the COP process, which was originally intended to negotiate a binding international treaty to limit emissions. The 1997 Kyoto Accord collapsed after COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009. In its aftermath, the 2015 Paris Agreement shifted to voluntary actions, in which individual nation-states proffered Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), laying out development pathways to limit emissions. A decade later, few nations are on track to meet their NDCs. With updates due by the end of the year, fewer than half of the participating countries submitted new NDCs in advance of the conference.

Instead, the world has made progress toward decarbonization and adaptation not because of the UN-led effort but in spite of it. The main drivers of emissions trajectories nationally and globally have always been macroeconomic and technological, not political. The primary determinants of climate impacts on human societies are socioeconomic, not climatological. Nations have always had good reasons to invest in energy technology innovation, promote socioeconomic development, and pursue resilience to natural disasters without any reference to climate change at all.

In the aftermath of the latest COP, much of the attention has focused on what was absent, not what was accomplished. The Trump administration not only pulled out of the Paris Agreement but chose not to send any official delegation to COP30 at all. Bill Gates, arguably the world’s most important climate philanthropist, announced in the run-up to the conference that he was shifting his focus from climate change to poverty alleviation and global health. Both moves have been widely criticized as blows to the climate effort. But it is entirely possible that they may do more to address the problem than anything produced at recent COPs.

Notwithstanding its climate skepticism, the Trump administration’s determination to double down on US natural gas production and exports is likely to accelerate the global coal-to-gas transition, while its unprecedented commitments to commercializing a new generation of advanced nuclear reactors could end up accelerating decarbonization in coming decades. Gates’s shift to poverty and public health, similarly, may do far more to improve resilience to climate extremes among the most vulnerable than the COPs’ long-running dramas around loss and damages and climate adaptation funding.

On each of these fronts, the COP conferences not only have proved to be a waste of time and resources but have often actively caused harm. Until recently, for instance, all discussion of nuclear energy, still the world’s largest source of clean energy, was limited to side events at COP meetings. COPs over the last decade have resulted in outright bans on investment by multilateral institutions like the World Bank in fossil fuel extraction and infrastructure in poor countries, which contribute almost nothing to global emissions and whose vulnerability to climatic extremes is due to energy poverty, not a changing climate. Rich country commitments to provide mitigation and adaptation aid to poor countries, meanwhile, have not increased the aid those countries receive. Instead, they have diverted funds from proven development activities such as education and public health programs toward dubious mitigation and adaptation projects.

Despite these serial failures and the harm that they have caused, there appears to be no interest at the UN or other quarters of the climate community in reconsidering whether the annual COP conferences serve any real purpose. Next year, all of the same players will gather in the Mediterranean resort city of Antalya, Turkey, to replay the same debates and drama that we just witnessed in Brazil. Billions of dollars that might be spent on bed nets or childhood vaccinations will instead be wasted on flying the global climate commentariat and the huge government, nonprofit, and corporate sustainability sector that has grown up around it to hobnob and speechify and make empty commitments. For this reason, it is not enough to simply ignore the UN’s annual climate bacchanal as a pointless contrivance. It’s long past time to abolish it.

Ted,

I get it, you're appropriately going after the Climate COP. You may be understating their historical significance, but they seem to have become are impotent, frustrating gatherings, perhaps a collective narcissistic bubble. Yet, the tone here is dismissive of the challenges - and dismissive of both the science and the risk. Atypical of your work to be simplistic in this way (and I mean that both as constructive and as a complement).

First, the science. A: The statistic that island nations are adding land through filling, etc., is a strawman argument about climate change risk, and plus this risk is not limited to islands (see king tides, globally). B: Humanity is pushing planetary boundaries as recently experienced during the Holocene. And no doubt human ingenuity will buffer accelerated warming (fusion, geoengineering, etc.). And also no doubt we will adapt, even to rising seas. Yet I'm trained as a geochemist and follow the abundantly compelling evidence of paleoclimatology. The last time there was 415ppm C in the atmosphere (ca. 3.2mya), mean sea level was 22m higher and mean global temps were approx 3 degrees C warmer. That's where we are headed, sans management of complex atmospheric chemistry. Granted, as a leading Greenland glaciologist told me, 'It is going to melt, but it is going to take centuries.' But 1.5 degrees, albeit somewhat arbitrarily selected as a political posture, is not without consequence.

Second, on risk. I am also trained as an economist and accept that we need to optimize current investments (good pt on Gates). Obviously, our definition of the problem does depend on our time horizon and the net present value of the future. (That economics, as a fair reflection of short-termism, poorly values intergenerational justice is a complex and big topic.) Yet, your assessment of climate-related risk aligns quite poorly with conclusions arrived at and policies enacted by the multi-trillion-dollar reinsurance industry, which is, not incidentally, quite attentive to the science). It's a bit of a throwaway analysis to say, 'we are wealthier and our lands more densely populated, so of course it's more expensive.' That, again, is a strawman argument if the intent is to define climate-disaster risk profiles. Looking at a point in time is meaningless. Any useful analysis is tied to a longer horizon, such as that of the 30-year mortgage. The math has to include reasonable projections of conditions is 2056.

So, go after the Climate COP all day long, and I'm right with you. And while we are at it, let's also deflate many irrational arguments that have at times annoyingly governed the climate conversation. But in the end, despite all our ideas and cherished debates, we are unwise to ignore the laws of thermodynamics.

Best, Robert Heinzman