Could the U.S. Unlock a Shale Revolution for Critical Minerals?

Tapping new critical mineral resources with technology and innovation

By Peter Cook

The history of the U.S. oil and gas sector over the last 50 years follows an extraordinary transition from scarcity to global competitiveness. Conventional U.S. oil and gas production peaked in the early 1970s, compounding a reliance on imports that began as postwar growth outpaced production. This reliance created vulnerabilities made famous by the 1973 OPEC embargo which quadrupled oil prices.

In response, the federal government worked with the oil and gas industry to further hydraulic fracturing, microseismic monitoring, and horizontal drilling techniques. These advancements enabled production from low permeability shale that previously allowed only marginal, small scale operations. The resulting shale revolution effectively supplemented the dwindling production from conventional reservoirs and helped lift the U.S. to net exporter status in 2017 for gas and in 2020 for oil.

Opportunities like the shale revolution may exist for certain critical minerals. Novel mineral resources or improved extraction techniques could boost production and overcome current limitations just as they did for the oil and gas industry. Advancements on this front may improve operational competitiveness, boost environmental performance, or even unlock new supplies of commodities not previously considered part of the U.S.’s available natural resource inventories.

For example, as China restricts its exports of gallium and tellurium, federal grants could equip domestic smelters to extract both metals from material currently discarded as waste. Or, manufacturers could make use of our abundant hydrocarbon resources to produce synthetic graphite alternatives that make up for relatively sparse natural graphite deposits.

Simply building new mines and securing foreign ore and metal imports are not enough for the United States to decisively win the critical mineral challenge. Instead, the federal government must learn from the shale revolution and seek out innovative and otherwise looked-over opportunities to drive a surplus of, not just meet current demand for, critical minerals.

Seizing unconventional critical material opportunities requires sustained commitment to research and development. The Trump administration has currently placed this commitment in question after canceling over $8 billion in federal funding for projects that would advance critical mineral supply chains, threatening key domestic investments like a new lithium refinery in Nevada. At the same time, the One Big Beautiful Bill’s addition of a phaseout over the years 2031-2033 for critical mineral production tax credits has weakened the economic case for more innovative ventures still in the earlier phases of planning.

While the Department of Energy has announced a compensatory $400 million to improve processing facilities capable of producing critical minerals, this salvages a relatively meager amount of investment in critical mineral technology, especially considering how previous projects like the Mountain Pass rare earth operation alone required nearly $200 million to develop heavy rare earth extraction capabilities that China currently employs.

A single breakthrough in a given mineral supply chain could take the U.S. from a position of scarcity to global dominance. National and economic security cannot risk forgoing these opportunities with such a narrow, inconsistent approach to public funding for novel critical mineral production. All mines eventually deplete and foreign trade relations can rapidly deteriorate. Research and development, on the other hand, can lead to innovations that lead to sustained gains in U.S. critical mineral security.

More minerals without more mining

Byproduct recovery and more efficient processing

Mineral byproducts provide a prime example of how technology can reduce supply chain vulnerabilities. Many critical minerals occur in minor amounts of ores of more major commodities. Cadmium, for instance, is present as roughly 0.03% of the mass of zinc ores. But to make use of such geological co-occurrences, smelters and refineries need particular equipment and process flows designed to capture trace elements as byproducts of their primary commodity.

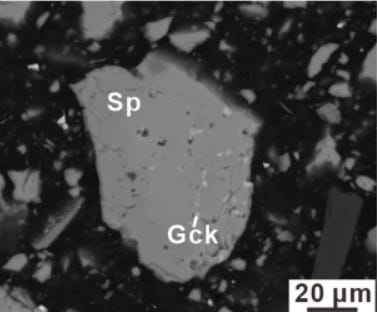

Scanning electron microscope image showing a small cadmium sulfide crystal (noted as “Gck” for the mineral greenockite) contained within a sphalerite crystal (noted as “Sp”), the principal ore of zinc. The incorporation of trace amounts of minerals like greenockite into sphalerite allows mineral processing facilities to extract cadmium as a byproduct from ores mined primarily for their zinc content.

The U.S. currently recovers cadmium as a byproduct of zinc ore and tellurium as a byproduct of copper ore. Other domestic processing facilities could considerably expand critical mineral production through byproduct recovery if properly equipped. These capabilities would create a new source of critical minerals that avoids the long lead times of opening new mines and makes use out of material that processing facilities currently discard as waste.

Outside of the U.S., niche practices employed mainly by China have proven capable of extracting gallium and germanium from zinc ores. The U.S. could apply similar techniques to its sole primary zinc smelter, introducing a supply of either critical mineral it currently must import.

The zinc smelter facility has cautiously estimated that byproduct recovery capabilities could yield enough gallium and germanium to meet about 80% of U.S. demand (~15 and 25 metric tons, respectively). Theoretically though, gains in expertise and improved practices could eventually yield on the order of 300 tonnes of gallium and 100 tonnes of germanium each year, allowing the U.S. to become a net exporter of the very same critical minerals that China has wielded as a trade weapon.

Similarly, the sole operating U.S. alumina facility could recover gallium when converting aluminum ore to alumina (the precursor to aluminum metal). This capability alone could satisfy national gallium demand of roughly 20 tons a year with proper facility upgrades and a reasonable 30% rate of gallium recovery.

Many other co-occurrences of critical minerals exist that the U.S. could tap into if it developed novel recovery techniques. Leading on this front could give the U.S. unique advantages in critical mineral production, potentially accessing cheaper, more readily available sources of minerals while other countries remain dependent on developing full-scale mines.

For example, the U.S. currently mines rare earth elements from carbonatite deposits at the Mountain Pass facility, but rare earths can also occur in iron-bearing deposits. The U.S. boasts robust pig iron production that could conceivably host rare earth element extraction. Historical pig iron mine tailings have already drawn interest from industry groups seeking out alternative inputs to the U.S. rare earth supply chain.

In addition to creating new supplies, the added revenue stream of byproducts could help domestic producers overcome economic challenges like low commodity prices and high operating costs. The last primary lead smelter in the U.S. closed in 2013 due to the cost of emissions compliance. Co-production of antimony and tellurium may have been able to keep the operation afloat.

In some cases, byproduct recovery could make an otherwise uneconomic resource viable. U.S. aluminum-containing bauxite ore, for example, contains high silica concentrations which requires more costly processing than imported ore. Added revenue from gallium recovery could potentially make domestic bauxite more economic and secure a domestic feedstock for the U.S. aluminum sector which currently relies entirely on imports.

The U.S. can also meaningfully boost critical mineral production by improving the recovery rates of mineral processing techniques, yielding more minerals from the same ton of ore. Tellurium, for example, which domestic producers source from copper ore, currently retains only about 1% of its original content across the entire supply chain. The milling stage alone—where mines crush ore into concentrates before sending to smelters—recovers only 10% of the original tellurium. A typical milling recovery rate for similar commodities hovers closer to 80%.

Poor tellurium recovery efficiency highlights the historic lack of industry incentive to orient processing facilities towards byproducts.

New deposits means new opportunities to excel

Unconventional critical mineral deposits

Even with improved processing efficiencies and byproduct recovery, new mining of other raw materials will clearly remain necessary to meet the broad mineral demand of any industrialized and growing society. Here, the U.S. can unlock new types of mineral deposits that the mining industry isn’t currently targeting by advancing geologic understanding of its domestic mineral resources.

The recently developed Brook mine in Wyoming, for example, originally intended to produce coal, but later discovered rare earth elements in shale layers interbedded between coal seams. The mining industry has vaguely known of the association of coal and rare earths for years now, but much of the focus, to date, has been on extracting rare earth elements from coal combustion products like slag and fly ash. A deeper understanding of the Brook mine’s geology could allow miners to precisely target rare earth elements in similar formations without needing to later extract them from power plant waste, thereby creating a new rare earth resource that can survive the uncertain future of coal power.

State geological surveys possess a wealth of historic rock samples that could reveal similar deposit types by reanalyzing samples for the presence of critical minerals that the industry did not originally have reason to look for. Positive results can provide vast amounts of data to develop understanding of new deposits faster and cheaper than drilling fresh core, and can direct industry efforts to promising targets. Led by the U.S. Geological Survey, the Earth Mapping Resource Initiative (Earth MRI) has pursued analyses from these repositories in addition to locating abandoned mine sites that could yield critical minerals by extracting trace amounts from old waste rock.

In some cases, technological advancements create a new geologic resource. Mining historically targeted lode deposits which contain the classic veins of, say, gold and silver that miners chased with pickaxes. The advent of modern earth moving equipment throughout the 19th and 20th centuries allowed industry to profitably mine low grade deposits where the mineralization instead occurs disseminated throughout the host rock.

Industry will always see some risk-takers that push the envelope of mining techniques, but federal partnerships can supplement private sector efforts and absorb risk as in the case of U.S. shale gas exploration. For example, geologic hydrogen could offer a carbon-free replacement for heat sources in industries that are difficult to electrify, like steel and cement manufacturing. In addition to aiding the search for sufficiently large deposits of geologic hydrogen, federal support can help tackle challenges to extracting it, like overcoming steel embrittlement during drilling and capturing the highly diffuse hydrogen itself.

Similar partnerships could help apply fracking techniques to another commodity with potentially significant future demand: uranium. Growing calls for expanding nuclear power, including recent Trump administration executive orders, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have placed a premium on developing domestic nuclear fuel supply chains. Domestically sourcing the raw uranium for nuclear fuel, however, faces economic hurdles since a lot of U.S. uranium reserves occur as hardrock deposits which require relatively costly underground or open pit methods to develop.

The U.S. produces some uranium through lower cost in situ recovery techniques which pump mineral-rich fluid from underground with less infrastructure and operating equipment than conventional mines. The limited domestic resources amenable to in situ techniques, however, has created an import reliance that will likely increase if industry does not tap into additional low-cost deposits.

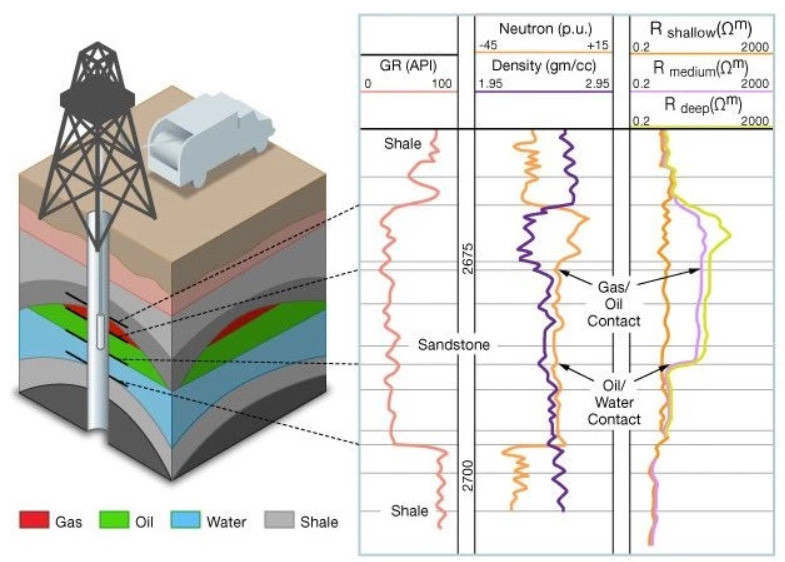

Here, shale formations may offer a breakthrough. Shales naturally contain elevated amounts of uranium. In fact, industry already uses this geological association when drilling for gas, using gamma ray detection to spot shale layers when drilling as shown in the figure below. While domestic shale could contain vast amounts of uranium, shale’s relatively low permeability would not allow production with conventional in situ techniques. Developing fracking techniques suitable for uranium production could provide the U.S. with a new, competitive uranium resource, possibly even making use of existing oil and gas production with uranium as a byproduct.

Subsurface drilling can detect shale layers based on spikes in gamma radiation due to the presence of radioactivity from elements including uranium (denoted in the figure above by “GR API”). Shale formations throughout the U.S. could potentially provide vast amounts of uranium used to fuel expanded nuclear power generation.

The U.S. should nevertheless strive to expand the use of in situ recovery techniques to other commodities, potentially unlocking more cost-effective alternatives for a number of critical minerals like nickel, cobalt, rare earths, and vanadium. Here, research and pilot studies can help identify the necessary additives that industry must inject underground to liberate the element of interest which can vary based on local geology. Uranium producers in Kazakhstan and Australia, for example, use sulfuric acid while U.S. uranium producers use alkaline mixtures.

In some cases, in situ recovery may allow the U.S. to produce minerals not currently available through conventional deposits. For example, the U.S. has not mined manganese as a primary commodity since 1973, with the recently developed Hermosa-South32 project mining manganese only as a byproduct of zinc and silver. In situ recovery could make use out of remaining manganese resources that otherwise occur in grades too low to economically mine using conventional techniques.

Innovation as critical mineral policy

As with the OPEC embargo, the U.S. must respond to growing critical mineral trade pressures. Domestic supply chains still face staggering import reliances for dozens of critical minerals essential to national and economic security, vulnerabilities that China has already taken advantage of with targeted export bans. The U.S. cannot afford to limit its critical minerals strategies to existing techniques or conventional deposits, and must consider broader opportunities to smash through the practical limitations that have imposed supply chain insecurities in the first place.

Innovation requires persistent policy support for mineral surveying, lab-scale research, and pilot projects that confidently survives different political administrations. The U.S. can potentially realize a shale-like revolution for one, two, or several critical minerals if policymakers commit to public-private research and development as a cornerstone of national critical minerals strategy. Over the next decade, technological breakthroughs can permanently bolster supply chains in ways that may well take the U.S. from supply scarcity to production dominance in key commodities.

Thanks for the article. The notion of leveraging technology to find novel ways to access to generate new sources of minerals is one I support.

I would note, however, that shale is not necessarily an example to emulate. It has many subtle factors that are not present in the case of mining and minerals. So if minerals is going to become as dynamic as shale proved to be, it will have to invent a new way. The primary spur to innovation is reward, so I believe that the prices would need to rise significantly and remain elevated for several years to draw attention, capital, and human resources. Right now, the size of the prize is too small.

I would have thought that this was pure pie in the sky stuff, but we are seeing expansion of geothermal projects. This shows that US industry can still pivot, so longas the government is looking somewhere else. . My worry about minerals is that they are too niche to attract academic investigation and venture capitalists won't fund them unless they get nominated as the next bubble stock. For the next few years AI is going to soak up all the attention and the money.

When the Trump administration has gone there may be a chance to rebuild America's technology base, readmitting foreign talent and finding ways to steer develop home-grown talent. At the moment the rest of the world is taking the opportunity to attract people away from the US.

Downsides apart, all of what you say sounds spot on. Geothermal mining technologies could be used to exploit low grade low-lying ores. The whole world, China included, wants to find ways of extracting rare earth metals at lower environmental cost. I suspect that China and Europe will get there first, but this will be new technologies where a country like America should have a chance of competing.