California Should Stop Forcing Drivers to Subsidize Deforestation

Why crop-based biofuels are undermining the state’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard

By Dan Blaustein-Rejto and Lauren Teixeira

California spent the past year congratulating itself for raising the ambition of its Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), the state’s flagship program to cut greenhouse gas emissions from transportation. In June 2025, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) approved sweeping amendments that accelerate carbon-intensity reductions across gasoline and diesel. The LCFS now aims to cut transportation fuel emissions far more quickly than ever before, reaching a 30% reduction by 2030 and 90% reduction by 2045.

Without further reforms, much of this decarbonization will exist only on paper. California’s efforts still lean heavily on corn and soybean-derived biofuels, which the state considers to be much less carbon-intensive than fossil fuels. But, that’s contrary to a growing body of research that finds the crop-based biofuels drive deforestation, grassland conversion, and other land-use change from Iowa to Indonesia.

California policymakers must now decide whether to align the LCFS with the latest scientific evidence, or continue subsidizing fuels that worsen the very problem the program is meant to solve.

How the LCFS Reshaped California’s Fuel Markets

The LCFS works by requiring fuel suppliers to reduce the average carbon intensity of the fuels they sell. Fuels below the benchmark generate credits; fuels above the benchmark generate deficits. Those credits are tradable, creating a market that rewards low-carbon alternatives.

Although the state’s long term vision for decarbonizing transportation is a pivot to electric vehicles, the LCFS has so far served mostly to put more biofuels in the tanks of the state’s trucks. Between the program’s beginning in 2011 and today, renewable diesel and biodiesel—the cheapest source of credits under the program—have gone from playing a negligible role in California’s diesel market to making up about 75% of it. (Renewable diesel is a clean-burning fuel made from plants or waste oils that works just like regular diesel in any engine, while biodiesel is made from similar sources but usually has to be blended with regular diesel to work properly.) Fuel sellers have passed on the cost of these biofuel credits to California drivers, who have paid around 18 billion dollars for biofuels since the start of the program.

This massive transfer of wealth from California consumers to mostly out-of-state biofuel interests would be at least somewhat defensible in terms of CARB’s mandate to reduce emissions if biofuels were a genuinely sustainable decarbonization strategy. But the most recent evidence indicates that they are not.

Crop-Based Fuels Are More Land-Intensive Than CARB Ever Modeled

Since at least 2008, researchers have raised concern that government support for crop-based biofuels could end up having a net negative effect on the climate. They hypothesized that producers in the tropics would respond to the higher vegetable oil prices induced by biofuel policy by clearing carbon-rich forest and grassland to make way for new oil crop plantations. Clearing acres of forests and grassland would release carbon into the atmosphere, potentially negating the emissions-reducing effect of replacing fossil fuels with biofuels.

When California first adopted the LCFS, however, there was scant empirical evidence on the land use impacts of biofuel expansion to support this hypothesis. CARB relied instead on GTAP-BIO, a model originally designed for trade analysis that attempts to represent the entire global economy. It estimated that government support for corn ethanol and soy biodiesel would in fact increase corn and soy prices. Initially the modeling even found that ethanol would result in enough deforestation to make it more carbon intensive than gasoline. But after pressure from California officials and the biofuels industry, as Michael Grunwald details in We Are Eating the Earth, the modelers made changes that made both ethanol and biodiesel look cleaner than fossil fuels.

Fifteen years later, the world looks very different. Biofuel markets have matured, and researchers have been able to conduct retrospective studies parsing the relationship between biofuel policy, crop prices, and land use. The most statistically robust studies consistently find that biofuels cause far more land-use change and emissions than GTAP and California ever predicted.

Tropical Deforestation: Vegetable-Oil Diesel and Palm Expansion

A new working paper from researchers at UC Davis and Berkeley, though not yet peer-reviewed, provides the clearest evidence yet. Between 2002 and 2018, nearly one-tenth of global soybean, palm, and other vegetable oil production was diverted to bio-based diesel, a shift the authors estimate raised palm oil prices by more than 20%. Although palm oil itself is not used for biofuel in the United States, vegetable oil markets are tightly linked: when biofuel demand pulls soy or canola oil into fuel, food and industrial users often replace it with palm oil. In fact, as the U.S. diverted more soy and other vegetable oil to biodiesel in this period, it ramped up imports, including a seven-fold increase in palm oil imports, contributing to the rise in prices.

Using high-resolution satellite data, the researchers find that this global price spike spurred 1.7 million hectares of forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia alone—about one-fifth of total forest-to-palm conversion in that period. The associated carbon emissions exceed 1 gigaton of CO₂, or the equivalent of adding 9 million cars to the road every year for 25 years.

Put another way, the emissions generated by the deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia linked to vegetable oil-based diesel alone (69 gCO₂e/MJ) come close to CARB’s current emissions limit for fuels to earn LCFS credits (80 gCO₂e/MJ). When also considering the emissions from producing soy-based biodiesel or renewable diesel, the total emissions for the so-called low carbon fuels are similar to or even exceed those from petroleum diesel. Considering that these estimates don’t include land conversion from any other parts of the world, such as the U.S. or Brazil, diesel from vegetable oils seems significantly more carbon-intensive than petroleum diesel.

U.S. Land Expansion: Converting Grassland and Conservation Farmland

Of course, soy biodiesel and other crop-based biofuels don’t only have international impacts. New research finds they have had a large impact on U.S. land use too. The only major statistical analysis of the land use impact of biodiesel estimated that each billion gallons of soy biodiesel has expanded U.S. cropland by roughly 1.87 million acres—an order of magnitude above CARB and other GTAP-based numbers.

Likewise, statistical analyses looking back at the past two decades of government support for corn ethanol have found that it spurred land conversion in the US. A 2025 EPA report estimated that each additional billion gallons of corn ethanol has caused up to 0.92 million acres of U.S. cropland expansion. Although this didn’t cause much domestic deforestation—most of the forest was converted long ago—it led to the conversion of pasture, grassland, and farmland that had been set aside for native vegetation through the national Conservation Reserve Program. This scale of land conversion has a large carbon cost: up to 30 gCO₂e/MJ, six-times higher than CARB’s estimate for emissions from domestic land-use change.

Tapped by the Biofuel Industry

Despite the mounting evidence that biofuels drive significant land-use change, CARB still relies on its decade-old estimates from the GTAP-BIO model. They’ve held onto this model due to institutional inertia and industry pressure, not scientific support. In fact, the model has several major shortcomings that have been frequently critiqued and that contradict the best science, contributing to its small estimates.

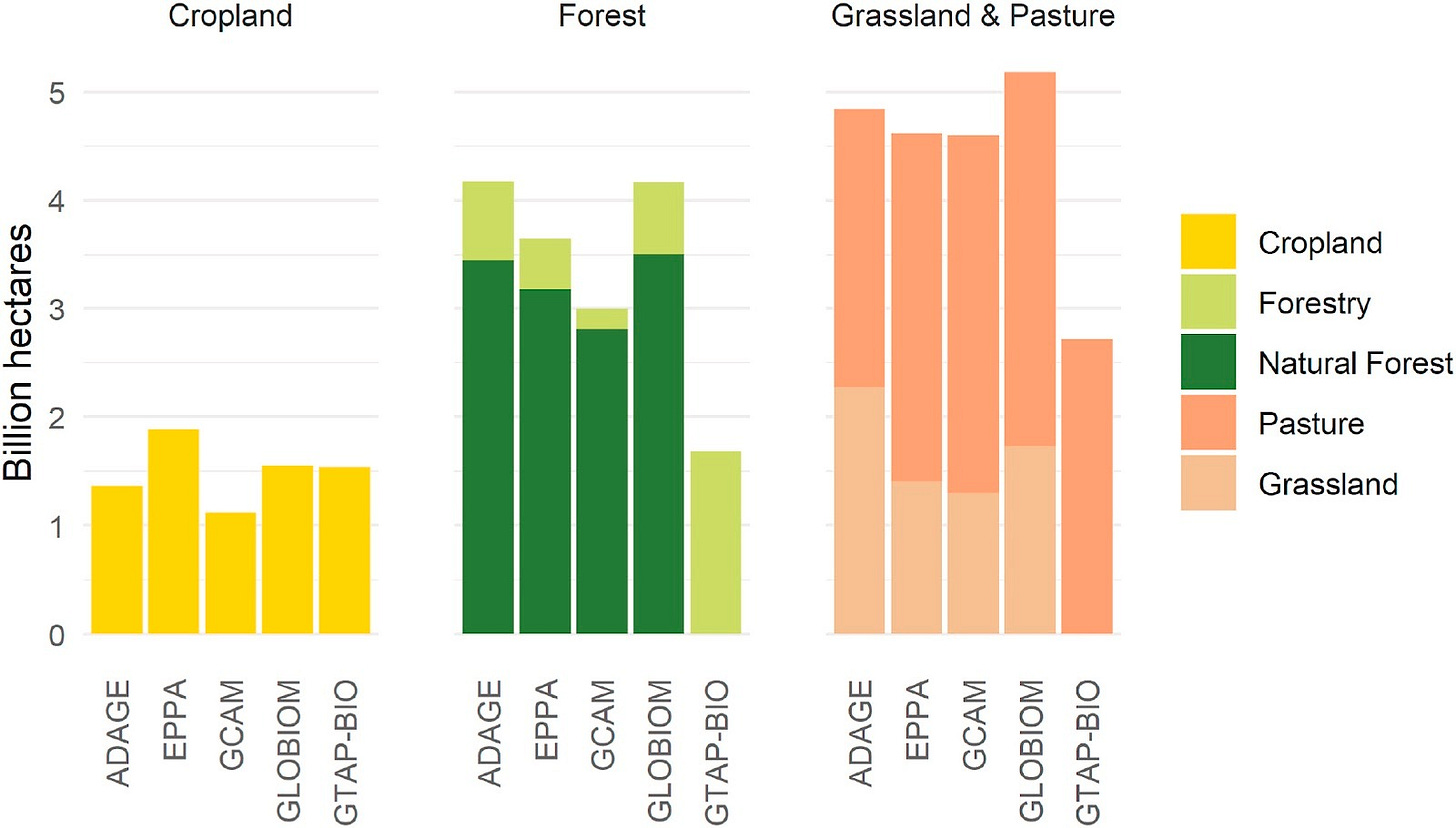

Most surprisingly, GTAP-BIO cannot model the conversion of any natural forest—including wild, old-growth, or other unmanaged forest—one of the most common and important types of deforestation. In contrast to other models, GTAP-BIO doesn’t account at all for unmanaged forest, which makes up about half of all global forest land. Among the many problems this poses is one of basic economics: the model artificially reduces the supply of forest land in the world available to convert, which increases the price of forest land, ultimately reducing conversion of it. Since forest land is treated as so valuable, the model even projects that when biofuels cause deforestation, people in other parts of the world will plant more forest in response. One study found that this limitation alone reduces the model’s estimates of land-use change emissions up to 32%.

California’s biofuel estimates rely on GTAP-BIO model that omits natural forest

In addition, GTAP-BIO implicitly credits biofuels for lowering global food consumption. When California studied the land use impacts of biofuels, they found that not all of the corn and soy diverted from food and livestock feed to biofuel would be replaced. In fact the State’s modeling assumed that as much as 44% of the corn used for ethanol wouldn’t be replaced and that due to higher prices people would consume less corn, whether in tortillas, cattle feed or other products. Reduced food consumption means less farming and thus lower estimates of land-use change. It also means more hunger, especially in low-income countries where people are most sensitive to increases in prices, including corn and soybean oil. Even the EPA, which has long defended its own national biofuel policy, acknowledges biofuels raise prices. Counting hunger as a climate benefit may be right analytically—growing less food does reduce emissions—but it’s wrong morally and undermines California’s commitment to reduce emissions in an equitable manner.

A number of other technical elements of the model run counter to recent science or common sense. For example, it assumes farmers respond to higher crop prices by increasing yields much more than the best empirical research finds. It also artificially limits the impact of U.S. biofuel demand on international trade and prices by assuming that consumers around the world strongly prefer corn, soy and other crops grown locally, despite evidence that corn and soy are traded internationally in a well-integrated global market. Taken together, the model’s many assumptions and limitations significantly reduce its estimates, consistently making them lower than those of other models.

It is no surprise then that industry groups have pushed CARB not only to stick with the GTAP-BIO model but to adopt more recent versions of it that generate even lower estimates. These modeling changes that CARB could adopt are technical and may appear small, but have large consequences. Industry groups are advocating for CARB to use land use change estimates for corn ethanol and soy biodiesel that are less than half CARB’s existing estimates. Adopting them could lead to over $100 million in additional credit revenue for biofuel developers, a windfall for an industry that is already well-developed.

The result is a classic case of regulatory capture: a well-organized industry benefits from putting its finger on the regulator’s scales, while the costs—deforestation, lost biodiversity, and more expensive food—are borne by people and ecosystems half a world away.

Capping Crop-Based Diesel Isn’t Enough

To its credit, CARB acknowledged these sustainability risks in its 2025 amendment by imposing a 20 percent cap on the share of each producer’s biomass-based diesel that can come from soy, canola, or sunflower oil.

This is a meaningful shift. It will prevent much more growth in diesel made from these crops. But it is not enough.

Crop-based diesel—not to mention ethanol—already has a large impact and California should seek to reduce it, not merely prevent it from growing. In 2024, the LCFS credited about 475 million gallons of soy- and canola-based diesel. Applying the recent estimate of vegetable oil-induced deforestation in Malaysia and Indonesia to those volumes indicates those fuels generated nearly 2.6 million tons of CO₂ more than CARB assumed. That’s equivalent to the emissions from about half a million cars, not even accounting for land-use change emissions from the U.S. or South America.

Critically, the cap also exempts jet fuel produced from vegetable oil. Biofuel producers can use soybean or canola oil to make alternative jet fuel and avoid the 20 percent limit entirely. Because alternative jet fuel generates large LCFS credits and airlines face few near-term alternatives to decarbonize, this loophole could spur a large increase in crop-based biofuel demand. As it stands, the alternative jet fuel market is already taking off in California, with 68% more of the fuel receiving LCFS credits in the first half of 2025 than a year earlier. Most of the fuel is currently made from byproducts like used cooking oil or animal fats, but there is limited availability of these. As alternative jet fuel demand grows, producers will need to turn to vegetable oils, boosting their use despite the new cap.

The cap also excludes used cooking oil and tallow, which are used to produce about half of the biomass-based diesel that CARB supports. Yet these also can spur deforestation. Used cooking oil and tallow are often already used outside of the biofuel industry, especially for livestock feed and products like soap, makeup, and industrial lubricant. Diverting the oil and tallow from these uses to the biofuel market raises demand for substitute products, mostly vegetable oils, indirectly driving land-use change.

Some used cooking oil and tallow is also directly tied to deforestation. A recent investigative report traced “renewable” diesel refined in Texas back to tallow from cattle raised on land cleared from the Amazon rainforest. And with the large premiums that used cooking oil can earn from the LCFS and other biofuel programs, there has been growing signs of fraudulent mislabeling of palm oil as used cooking oil.

California Must Reform the LCFS to Protect Its Climate Integrity

None of this undermines the LCFS’s fundamental design. As a technology-neutral, performance-based standard, it resembles the clean energy standards that many groups—including BTI—have long championed. It harnesses market forces and has helped accelerate vehicle electrification.

But the program’s integrity depends on accurate carbon accounting. Land-use change emissions from biofuels are large enough that even moderate use can offset much of the LCFS’s climate progress.

California must reform the LCFS. That should include updating land-use change calculations using the best available empirical evidence and closing the aviation loophole that allows unlimited crop-based jet fuel. CARB must also consider broader program-wide reforms: reducing the use of crop-based biofuels would raise credit prices, potentially to levels that consumers and politicians wouldn’t stomach. Additional reforms, such as reducing the ambition of the LCFS, will therefore be needed to protect consumers from higher costs while ensuring the program’s integrity.

Other states like New Mexico and New York are now adopting or scaling up their LCFS-style programs. Unless California corrects course, it will export the LCFS’s deforestation footprint nationwide.

Clean energy programs only work when they can identify which energy sources actually reduce emissions. For the LCFS, that reckoning is overdue.

Thanks. I have been wondering for many yearsjust how long and how many dollars California consumers will bear the cost of the LCFS. for many years, it was reasonable to assume that other states would adopt California initiatives. But it has become clear in the last decade that other states will not, at least many will not, emulate. That leaves the California consumer as an outlier. And that means a lot of risk for every biofuels business in Sacramento. The entire biofuels market could collapse if the state dropped the program.

Thanks for the article.